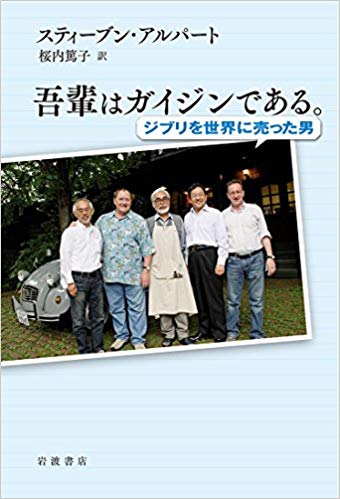

Books: Gaijin at Ghibli

June 27, 2018 · 0 comments

By Motoko Tamamuro.

There are plenty of books written about Studio Ghibli, although it is difficult to tell how well they sell. Hayao Miyazaki’s collected writings seem to do well enough for Viz Media, but producer Toshio Suzuki’s memoirs only limped out from a small, expensive academic press. Perhaps these diminishing returns explain why Stephen Alpert’s exciting, dishy insider account, I am a Gaijin: The Man Who Sold Ghibli to the World has only been published in Japanese, despite being originally written in English.

There are plenty of books written about Studio Ghibli, although it is difficult to tell how well they sell. Hayao Miyazaki’s collected writings seem to do well enough for Viz Media, but producer Toshio Suzuki’s memoirs only limped out from a small, expensive academic press. Perhaps these diminishing returns explain why Stephen Alpert’s exciting, dishy insider account, I am a Gaijin: The Man Who Sold Ghibli to the World has only been published in Japanese, despite being originally written in English.

Alpert worked at Citibank and Walt Disney Japan before moving to Ghibli in October 1996, just as production got underway on Princess Mononoke. His boss, Toshio Suzuki, head of Ghibli and second-in-command at its Tokuma Shoten parent company, gave him a simple mission: “Alpert-san, what we want you to do is to take our movies to the world and make them successful. By successful, I mean critical acclaim and making money. Of course, we’d like both, but if you can’t achieve either, you will be fired.”

Alpert was assigned to oversee Tokuma’s international affairs, mainly Ghibli, three months after the studio signed up with Disney’s distribution arm. Disney would begin with Princess Mononoke in theatres, and eight videos in US stores. The impetus for this historic deal dated back a further two years, when Koji Hoshino, the head of Buena Vista Japan, was desperately trying to secure the video software rights for Ghibli films in the Japanese market. Tokuma refused to play along, until the day that Suzuki made him an offer. Buena Vista could have the Japanese video rights, on the condition that Disney would distribute Ghibli’s next film in the US.

Alpert was assigned to oversee Tokuma’s international affairs, mainly Ghibli, three months after the studio signed up with Disney’s distribution arm. Disney would begin with Princess Mononoke in theatres, and eight videos in US stores. The impetus for this historic deal dated back a further two years, when Koji Hoshino, the head of Buena Vista Japan, was desperately trying to secure the video software rights for Ghibli films in the Japanese market. Tokuma refused to play along, until the day that Suzuki made him an offer. Buena Vista could have the Japanese video rights, on the condition that Disney would distribute Ghibli’s next film in the US.

Suzuki wanted plaudits in what he calls “the major league” of the film industry, because success in Hollywood would increase his domestic revenue. Foreign critical acclaim is a powerful marketing element in Japan, where audiences often place a higher value on things if they are accepted internationally. But Studio Ghibli, and its eccentric creators Hayao Miyazaki and Isao Takahata, were renowned for refusing to compromise. Every single filmic detail was scrutinised and put in place for a reason. They hardly ever pandered even to the Japanese, let alone audiences abroad. Just how Alpert managed to steer a stubborn studio into a worldwide mega-brand is the subject of this book, two-thirds of which are dedicated to the difficulties he faced on Princess Mononoke.

Disney executives like Michael O. Johnson, the president of Walt Disney International, had only seen Castle in the Sky, My Neighbour Totoro and Kiki’s Delivery Service, and were expecting similar child-friendly films when they took on Ghibli’s world distribution. Johnson was hence entertainingly horrified when he visited the Tokyo office and saw clips of the film in production, including a graphic moment of decapitation, and the heroine wiping blood around her mouth. Johnson begged Suzuki to change it, pleading that his own head would roll unless he could deliver something more sedate: “Do we have to have the arms and heads flying off? Isn’t there something softer in the film? Romance maybe? Can’t I get a nice romantic scene, you know, between the hero and heroine? Maybe a kiss or something?” The final cut of the trailer included a shot of the wolf-girl San feeding Prince Ashitaka a piece of meat, mouth-to-mouth. Johnson went away delighted, and nobody corrected him when he thought he’d just witnessed a tender kiss. Alpert repeats this story like the victimless crime it ultimately was – record-breaking Japanese box office sales for Princess Mononoke more than justified Disney’s backing.

Alpert outlines the cultural differences between the US and Japan in the boardroom. The Japanese, accustomed to doing business on trust, were baffled by American contracts that spanned hundreds of pages of eye-watering minutiae. But Ghibli surely had every reason to lean on written agreements, particularly after Princess Mononoke ended up not at Disney’s children’s entertainment arm, but at its edgier Miramax subsidiary, under the rule of the notorious Harvey Weinstein. This led to one of the most famous anecdotes in anime history, after Suzuki sent Weinstein a sword with the stern note attached: “NO CUTS!” Surprisingly, Alpert reveals that the contract specifying “no changes or alterations to the original” was nothing to do with Japanese demands. In fact, the clause was thrown in out of respect to Ghibli’s creative work, by Disney executives who thought they’d be getting something along the lines of Totoro.

Much of the gossip in I am a Gaijin comes from the attempts by the American side to walk this rash promise back, and the battles of Ghibli staff to keep the foreign release as close to the original as possible. Alpert credits Weinstein with recommending Neil Gaiman to work on the English script, depicting the Sandman author as an ardent ally who understood Miyazaki’s creative vision. But other Miramax staff attempted to interfere with buzzwords and hacks straight out of film school. Others were determined to dumb it down, pushing the notion of “translation” into a directive to change anything that hypothetical American viewers might not like. Chief among the American complaints was that the film lacked clear heroes and villains, forcing Alpert to explain to the would-be meddlers that they were paying, in part, for Miyazaki’s mastery of nuance. Miramax pushed for the story to be simplified, and for the cramming in of expository dialogue, but Miyazaki refused to underestimate his audience, and Gaiman backed him up.

However, this caused Gaiman to be edged out of the loop. When he submitted a draft of his script, everybody assumed he was finished, and it was handed to a rewriter who started slicing it up so it fits the mouth movements, to the point where only the bare bones of Gaiman’s version remained. By the time Alpert saw the script again, with voice-recording about to start, little of Gaiman’s version survived, and a furious rear-guard action commenced to reinstate his lines, while the actors waited. In the end, much was salvaged by the audio director Jack Fletcher, who recorded multiple alternatives so that everyone could argue about it in post, and not while Claire Danes and Billy Crudup were on the clock.

However, this caused Gaiman to be edged out of the loop. When he submitted a draft of his script, everybody assumed he was finished, and it was handed to a rewriter who started slicing it up so it fits the mouth movements, to the point where only the bare bones of Gaiman’s version remained. By the time Alpert saw the script again, with voice-recording about to start, little of Gaiman’s version survived, and a furious rear-guard action commenced to reinstate his lines, while the actors waited. In the end, much was salvaged by the audio director Jack Fletcher, who recorded multiple alternatives so that everyone could argue about it in post, and not while Claire Danes and Billy Crudup were on the clock.

Alpert’s audio issues did not end with the dialogue. Miramax engineers added new sound effects not approved by Ghibli. Once again, Fletcher came to the rescue, arriving partway through the mix and furiously ordering the erasure of all the unsanctioned noises. But Alpert’s biggest challenge was Miyazaki himself, who was deeply reluctant to travel abroad for promotion. Refusing to acknowledge marketing as a vital part of the film production chain, Miyazaki preferred to expend his energies on the next film, rather than thinking about the one he had just finished. Only Suzuki was able to entice him into eight-hour days of constant interviews, wearily dealing with journalists who have not seen the film.

Despite the active verbs of the book’s title, Alpert does not personally claim the credit for Ghibli’s overseas success, instead emphasising that Toshio Suzuki was the real brains of the outfit, and he merely his assistant. Nor does he lay the achievement solely at Ghibli’s door, noting that many high-profile foreign Ghibli fans decloaked to push the film into markets overseas. In particular, he notes the pivotal role of John Lasseter, the chief creative officer at Pixar and long-time friend of Miyazaki’s, in offering both public and private support.

Alpert’s book presents a fascinating account of Ghibli’s development from a business point of view, alongside cross-cultural comparisons not merely with the US, but also with China. But Alpert never comes across as a hard-nosed numbers man, instead portraying himself as a Ghibli fan frantically trying to explain things to people around him – commenting, only partly in jest, that 80% of his job was explaining. He writes this memoir with humour and plenty of intriguing asides, about everything from food to Miyazaki’s secret love of port.

The title – I am a Gaijin – knowingly pastiches Natsume Soseki’s I am a Cat, the protagonist of which is a cynical outsider observing human behaviour. A gaijin is a foreigner, not particularly derogatory these days, although the author demonstrates palpable frustration at still being treated like an outsider after decades in Japan. But at least part of Alpert’s “outsider” status is a reflection of the gap between creatives and businessmen – he feels unable to celebrate with the crew when a film is complete, because his job is only just beginning as theirs ends. His title demonstrates his self-deprecation, but is also cannily chosen to appeal to Japanese readers. Alpert innately understands that Japanese people love to hear about how the world sees them, and by presenting himself as an outsider on the inside, he puts himself in a favourable position. Parts of this book did formerly appear in English online as Alpert’s Ghibli diary, although only fragments survive today and he seems reluctant to publish it outside Japan. Surely it’s high time that English readers got the chance to get the whole story…?

I am a Gaijin: The Man Who Sold Ghibli to the World is published in Japanese.

anime, books, cinema, Hayao Miyazaki, Japan, Motoko Tamamuro, Stephen Alpert, Studio Ghibli, Toshio Suzuki

Leave a Reply