The Elegant Life of Mr Everyman

February 21, 2016 · 0 comments

By Andrew Osmond.

The Elegant Life of Mr Everyman is one of the oldest films screening in the current Japan Foundation Touring Film Programme; it was released back in 1963. Directed by Kihachi Okamoto, it’s an observational comedy, voicing the frustrations and neuroses of the ordinary working man when the shade of World War II still lingered. Given how that ended for Japan, one of the film’s surprises is how much it breaks Basil Fawlty’s maxim, talking a great deal about the war.

The Elegant Life of Mr Everyman is one of the oldest films screening in the current Japan Foundation Touring Film Programme; it was released back in 1963. Directed by Kihachi Okamoto, it’s an observational comedy, voicing the frustrations and neuroses of the ordinary working man when the shade of World War II still lingered. Given how that ended for Japan, one of the film’s surprises is how much it breaks Basil Fawlty’s maxim, talking a great deal about the war.

It’s a live-action film of interest to Japanese animation fans, as it uses several cartoon scenes alongside jump cuts, smash cuts, freeze-frames, audio-visual dissonances and absurdist moments which could be fairly called cartoony. As it happened, I saw the film the same evening as the fourth-wall-smashing, Voltron-worshipping Deadpool. While Everyman has none of that film’s crazy swearing, sex or violence, its cinema vocabulary isn’t far removed from the super enfant terrible.

Everyman is less a story than a portrait of the title 36 year-old blinking, bespectacled salaryman – punningly called “Eburi” – and his family, especially his scoundrel father. Eburi, played by Keiju Kobayashi, works at an ad agency; one night he drunkenly agrees to write a story for a print magazine. Struggling for inspiration, he opts to ramble about his life, much like the confessional columnists or comedians today. The film is largely told through his voice-over commentary, swinging between Pooterish self-importance (such as Eburi’s pride that his company-house garden is fractionally bigger than his neighbours’) and painful self-awareness, while the tone turns tragicomic.

For British viewers, the humour has fascinating points of contact with Tony Hancock, another postwar Everyman. One can imagine Hancock in some of the scenes, even an absurdist highlight where Eburi leaves the house in his underwear while the narrator comments on his various layers of clothing. A flashback where Eburi fouls up an army training drill can’t help make one think of Dad’s Army (though Everyman was first). In anime, the closest comparison is with Takahata’s My Neighbours the Yamadas; perhaps Everyman was one of Takahata’s inspirations.

For British viewers, the humour has fascinating points of contact with Tony Hancock, another postwar Everyman. One can imagine Hancock in some of the scenes, even an absurdist highlight where Eburi leaves the house in his underwear while the narrator comments on his various layers of clothing. A flashback where Eburi fouls up an army training drill can’t help make one think of Dad’s Army (though Everyman was first). In anime, the closest comparison is with Takahata’s My Neighbours the Yamadas; perhaps Everyman was one of Takahata’s inspirations.

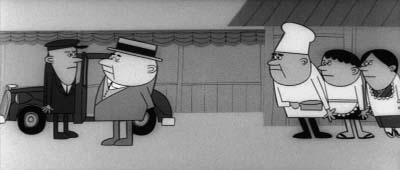

Everyman was made the same year as Astro Boy, often counted as the starting point for modern anime. However, Everyman’s own animated scenes don’t owe anything to Astro Boy, but rather to Japan’s already bustling industry of animated TV commercials. The animation was created by Ryohei Yanagihara, who had designed a 1958 cartoon advert called “Torys Bar.” It was placed in a Wild West setting, reflecting the pervasiveness of the Western in postwar Japan – a TV Western is glimpsed during Everyman.

Both “Torys Bar” and Everyman’s cartoon scenes reflect the influence not of Disney but another American studio, UPA, whose modernist, semi-abstract style was acclaimed in the 1950s. (Yanighara cited UPA’s most famous cartoon, the Oscar-winning Gerald McBoing Boing.) Unlike much anime, the movement of the characters is fluid, while the backgrounds and characters are simply drawn, sometimes reduced to symbols like those for a man and a woman. One brief scene in Everyman involves not drawings but stop-motion, used to animate some shoes. Stop-motion had been used both for Japanese commercials, and for the 1960 cartoon, The New Adventures of Pinocchio, animated in Japan for the American studio Rankin-Bass. (For more on Japan’s animated adverts, see this article and Chapter 4 of Anime: A History.)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=20SCQYPoJ6Y

In “Salaryman,” animation is used as part of a freeform film grammar (much as it’s used in Deadpool!) There are frequent freeze-frames; a sequence where Eburi pontificates in the office in front of his ‘frozen’ co-workers; non-diegetic sound effects, as when two gossiping women have their speech replaced by machine-gun fire; and ironic montages of groovy twisting youngsters, intercut with images of Japan’s burgeoning industry.

Some of these devices may have influenced Satoshi Kon, together with the tart humour. (Kon once said he liked leaving audiences unsure if they should be laughing at characters or pitying them.) Some of Salaryman’s humour is shockingly black. When Eburi’s aged mother-in-law dies, Eburi looks at his wailing father and wonders if he could ever equal his patriarch’s “performance.” The subsequent scenes become even more painful, taking us through the wake and into Eburi’s father’s debauched widowerhood, like Tokyo Story’s last act retold by Todd Solondz.

The father subplot has some of the most overt commentary, exploring Eburi’s simultaneous contempt for his dad and his urge to understand him. We’re shown how the father profited in World War II despite his fecklessness in business; after the war, he starts a succession of doomed small companies and races away from the (animated) creditors. A lot of this parallels Hayao Miyazaki’s ambivalent comments about his dad in the Starting Point and Turning Point books, as well as the documentary The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness.

Salaryman blurs Ebiru’s feelings about his father with his views on Japan, which are the focus of the last scenes. By now, Ebiru’s writings have found success and a following, and we see him holding forth to youngsters who are shocked and amused by his pronouncements. It’s where we expect the film to end… but instead director Kihachi Okamoto lets the sequence run on, and on, and on. The film traps the audience with Ebiru as he moves to bars and then home in the small hours, forcing his reluctant on-screen companions to accompany him.

Salaryman blurs Ebiru’s feelings about his father with his views on Japan, which are the focus of the last scenes. By now, Ebiru’s writings have found success and a following, and we see him holding forth to youngsters who are shocked and amused by his pronouncements. It’s where we expect the film to end… but instead director Kihachi Okamoto lets the sequence run on, and on, and on. The film traps the audience with Ebiru as he moves to bars and then home in the small hours, forcing his reluctant on-screen companions to accompany him.

It’s another peculiar joke, making us the captive audience of a drunken bore (though some viewers may be tempted to bail out early). But eventually Eburi’s ramblings about Calpis and sports meets give way to bitter railings against the malign or stupid 1930s generation who led Japan to war – “Shameful! Shameful!” As Eburi himself falls asleep, his long-suffering wife is left reading a love-letter from a history book, sent to a soldier who died in World War II. The letter has all the doomed passion, the intense love, which seems to have deserted the Japan of the film’s present. Ultimately the film, for all its modernist devices, seems to despair of understanding the past, and thus of comprehending the present.

The Elegant Life of Mr Everyman is screening in several UK cities as part of the Japan Foundation touring film programme, alongside other works such as Miss Hokusai and Anthem of the Heart.

cinema, Everyday Life of Mr Everyman, films, Japan, Japan Foundation, Kihachiro Okamoto, Ryohei Yanagihara

Leave a Reply