Books: Ambient Media

November 13, 2017 · 0 comments

By Jasper Sharp.

Studies of Japan’s media have predominantly focused on commercial cultural products such as anime, manga, film, music and literature, while sidestepping the provocative notion that, with its variegated patchwork of sounds, flashing lights and screens that play such a key role in defining the moods and tempos of its distinct urban areas, Japan is media. As trite and tendentious as this statement may seem, Paul Roquet’s Ambient Media: Japanese Atmospheres of Self, an exploration of the history of the constantly shifting streams of background noises and images, certainly encourages one to think along these lines.

The cacophony of competing signature tunes announcing the arrival of individual trains. The synthetic background bird tweets in public toilets aimed at drowning out audible bodily emanations. The izakaya bar that signals that it is home time with a spectacular LED fireworks display unfurling across across its ceiling. These are the memories that spring to mind when I think of Tokyo.

Roquet points out that the term “ambient medium” dates back to Isaac Newton’s 1704 study Opticks to describe the atmosphere surrounding the human body and separating us from external objects. Over the following centuries, the words “atmosphere” and “media” diverged from their near synonymous meanings, with atmosphere taking on new nuances to refer to the general feel and emotional tone of a particular place. Media no longer merely refers to the air, water or whatever other substance through which light and sound travels to reach us, but physical objects such as printed paper, canvas, celluloid, vinyl and magnetic disks. In our brave new digital age, we see both carrier and content as encapsulated within this single term. Meanwhile, the word ‘ambience’ has developed its own hues, with its emphasis on a human perception that is embodied, or somatic, rather than actively focussed through eyes and ears.

Roquet suggests that with “media” as omnipresent as the air we breathe, it might be time to see these two terms as converging once more, and what better entry point than Tokyo, “with its endless maze of carefully curated spaces.” Of particular interest for the author is the role these artificial sights and sounds play in providing “an interface between the rhythms of the body and the surrounding city”, a healing cushion from the noise, stress and bustle of metropolitan living.

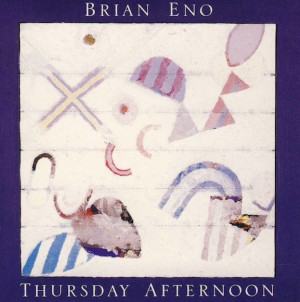

The concept of ambient music, both for public and private consumption, can be charted back to Brian Eno’s 1978 album, Ambient 1: Music for Airports. Eno’s proposal in the liner notes for a new form of music that is “as ignorable as it is interesting” found a natural home in Japan, and a swathe of local musicians soon followed his lead. Eno himself was commissioned by Sony 1984 to write the 61-minute composition Thursday Afternoon, in order to showcase both the sonic range and the storage capacity of the new CD format.

The concept of ambient music, both for public and private consumption, can be charted back to Brian Eno’s 1978 album, Ambient 1: Music for Airports. Eno’s proposal in the liner notes for a new form of music that is “as ignorable as it is interesting” found a natural home in Japan, and a swathe of local musicians soon followed his lead. Eno himself was commissioned by Sony 1984 to write the 61-minute composition Thursday Afternoon, in order to showcase both the sonic range and the storage capacity of the new CD format.

One of the pioneers in Japan’s ambient field, Haruomi Hosono, a member of legendary electronica group Yellow Magic Orchestra, once pointed out that “one of the unique things about the contemporary Tokyo landscape is that due to the absence of a grid system and the way the preponderance of tall buildings tends to block out what might otherwise have served as orientating landscapes… there is little sense of a stable background against which urban life transpires.” This remark goes some way in explaining why the ebbing and flowing soundscapes of this new musical form seemed so well suited to Japan’s environment.

The idea of music as a mood regulator and performance enhancer goes back much further than Eno. The first documented use of Background Music (BGM) in an industrial setting occurred in a Chicago automobile plant as early as 1886. In Japan, the Imperial Silk Factory in Yamanashi found in 1932 that playing popular music over speaker systems increased the efficiency of its workers by as much as 10%.

The term ‘muzak’ had entered the English lexicon even before it was trademarked in the mid-1950s by the American company responsible for producing elevator music. Soon after, a number of companies emerged in Japan to provide sonic wallpaper for a variety of consumer environments, such as hotels, restaurants, banks and shopping malls, with Akira Nagamatsu of Japan’s exclusive Muzak affiliate, the Mainichi Music System, introducing the preferred term of “environmental music” (kankyo ongaku) in 1966.

Early on, a variety of figures in the arts started offering their own creative responses to this omnipresent form of mood regulation. “The Mood Bath” a short story by the science-fiction author Juza Unno was published as early as 1937 as a satirical riposte to the Japanese government’s pressure on national radio stations to get the population all marching to the beat of the same drum. In the late-1960s, the short-lived artistic collective The Environmental Society created interactive installations in public spaces that adopted “classic avant-garde principles of play, experimentation, and the creative potential of discomfort.”

Early on, a variety of figures in the arts started offering their own creative responses to this omnipresent form of mood regulation. “The Mood Bath” a short story by the science-fiction author Juza Unno was published as early as 1937 as a satirical riposte to the Japanese government’s pressure on national radio stations to get the population all marching to the beat of the same drum. In the late-1960s, the short-lived artistic collective The Environmental Society created interactive installations in public spaces that adopted “classic avant-garde principles of play, experimentation, and the creative potential of discomfort.”

Coinciding with the introduction of Eno’s seminal work, the mid-70s also marked a mini-boom of popularity in Japan for the “furniture music” of French modernist composer Erik Satie (1866-1925), whose soporific melodies I didn’t think I was familiar with until a quick internet search revealed the kind of anonymous, anodyne ubiquity we now associate with Sigur Rós.

Roquet charts the form and function of ambient music across several generations of practitioners, and how it has both shaped and been shaped by the social and technological landscapes of the age. He wisely avoids drawing a lineage back to Japan’s pre-modern aesthetic traditions of Zen minimalism, instead focussing on how ambient culture evolved alongside the massive urban redevelopments of the 1960s (characterised by Tokyo’s hosting of the 1964 Summer Olympics) and the growth of neoliberalism as a guiding force for the economy in the 1970s, “an ideology that depends on sustaining the illusion of an autonomous self.”

According to Japanese sociologists, the late-1970s marked a notable turning point from the mass culture (taishu bunka) of the preceding postwar decades to the emergence of “micromasses”, distinct groups with interests in a variety of individual pursuits, be they consumerist, health-oriented or spiritual in nature. Is it any surprise that it was Japan that came up with the concept of the portable music player with the launch of the Sony Walkman in 1979, with its capacity to immerse the individual listener within soundscapes of their own choosing, but equally importantly, to mute the aural dissonance of traffic and other heightened noise levels associated with high-density urban living and pass the long and stressful hours spent commuting?

The role of ambient media is to provide a stable background “to align the somatic self with the fluctuating rhythms of the city”, and crucially, not just in sonic form. Screens abound within the Japan’s urban cityscape, like wormholes “capable of linking everyday locations and their subjects to wider, abstracted realms of commerce, culture and control in any number of ways.”

Roquet details the emergence of elevator muzak’s visual equivalent, the Background Video (BGV) or ‘environmental video’ (kankyo bideo), in the 1980s. The brainchild of Man Arai of the Dentsu advertising agency, these rhythmic, non-narrative images of cherry blossoms, waterfalls and exotic landscapes playing out in long, single-shot static takes are aimed at bringing a sedative calm to the restaurants, shopping malls and other spaces in which they are installed.

Titles for private viewing also emerged, with the book’s introduction detailing a typical example, Jellyfish: Healing Kurage (2006), a title which demonstrates how “through the repetition and overdetermination of similar affective cues in different aesthetic and sensory registers… a strong mood can be established even if audiences are only partially attentive to the screen.” The “soft fascination” of the environmental video, with its flat or layered compositional styles and lack of human focus in favour of repetitive organic imagery, both provides visual interest and an opportunity to space out and let the mind drift aimlessly, like a jellyfish.

The discussion of ambient media in all its guises stretches beyond gallery pieces such as Swimming in Qualia (2007), an installation with visuals by Shoko Ise set to a score by Steve Jansen (former drummer of the English electro-pop band Japan) to Jun Ichikawa’s self-referential “mood film” Tony Takitani (2004) and the comfort-blanket prose of authors like Banana Yoshimoto, whose best-known book Kitchen first appeared on Japanese bookshelves in 1988, and more recently, Yuki Kurita: their paperbacks are themselves likened to the Walkman as “a mobile technology of mood regulation.”

I absolutely loved Ambient Media, although there’s no denying it, it is an intellectually dense and rigorous work. Its unique subject matter makes for a compelling read, and admirably for an academic publisher, University of Minnesota Press have a pricing strategy that doesn’t place this book beyond the grasp of layman readers.

Beyond the more theoretical passages, Roquet also offers intriguing case studies of individual practitioners working in their respective ambient media that inspire one to check out their work, from musicians and sound artists such as Tetsu Inoue and Chihei Hatakeyama to experimental filmmakers like Masakatsu Takagi, while displaying a remarkable talent for poetically evoking Tokyo’s various landscapes and accompanying soundscapes through lively descriptions of often highly abstract aural and visual material.

Ambient Media concludes with various critiques of Japan’s all-encompassing comfort culture, including cultural commentator Akira Asada’s dismissal of the country’s “infantile capitalism”, later elaborated upon by the academic Tomiko Yoda as a “noncoercive force that controls individuals by ‘wrapping’ and ‘embracing’ them in its fold.”

This final chapter harks back to an earlier anthropological study in the UK by Michael Bull that analysed the various tones and tempos of the music contained on the iPod playlists people use to get them through the various stages of their working day, which suggests “just as users wish to liberate themselves from the oppressive rhythms of daily life, so they appear to sink deeper into them.”

Ambient media might be far more pervasive in Japan than in other countries, but its role in sustaining rather than soothing our current post-industrial malaise is worth thinking about. As in so many respects, it seems that where Japan leads, the rest of the world follows. Now where can I get hold of that jellyfish DVD?

Paul Roquet’s Ambient Media: Japanese Atmospheres of Self is out now.

Leave a Reply