Giovanni’s Island and the Galactic Railroad

March 16, 2015 · 1 comment

By Andrew Osmond

Giovanni’s Island is a blend of history, fiction and fantasy. The main story is about two young brothers, and what happens to them when their home, an island to the north of mainland Japan, is occupied by Russians at the end of World War II. But mixed into the drama are the boys’ fantasies about a steam train which travels through the stars, searching for the True Heaven. These fantasies aren’t just about escaping the world’s hardships. They’re a way for kids to understand the world, to fight through it, to transform fear, pain and even death.

Giovanni’s Island is a blend of history, fiction and fantasy. The main story is about two young brothers, and what happens to them when their home, an island to the north of mainland Japan, is occupied by Russians at the end of World War II. But mixed into the drama are the boys’ fantasies about a steam train which travels through the stars, searching for the True Heaven. These fantasies aren’t just about escaping the world’s hardships. They’re a way for kids to understand the world, to fight through it, to transform fear, pain and even death.

It’s not the first film to use this device. Guillermo del Toro’s celebrated live-action film Pan’s Labyrinth (2006) interwove the historical violence of Franco’s Spain with a young girl’s terrifying fairy-tale adventures (two words: Pale Man ). An earlier film, 1973’s Spirit of the Beehive, was also set against Franco’s Spain, where another girl dreams of the Frankenstein Monster, turning it into a benign woodland spirit not unlike Miyazaki’s Totoro.

It’s easy to enjoy Giovanni’s Island without knowing the real book which inspires the boys’ dreams. But if you want to know why it’s left such an impression on Japanese kids, read on…

Racing from the void, golden against the blackness, a square of light fills the universe. “It’s a field of corn!” exclaims one of the child adventurers, who happens to be a human-sized cat. Their steam train pulls in at a deserted, sun-drenched platform. Overheard, suspended from nothing, is a clock from which a gleaming pendulum swings, crisply clacking like a heartbeat. Music throbs softly through the cornfield from an invisible orchestra. A human girl leans forward. “That sounds like the New World Symphony…”

This is a scene from the anime version of Night on the Galactic Railroad. It’s known by variant English names, such as Night of the Milky Way Railway; the Japanese title is Ginga Tetsudo no yoru. The original was a Japanese novella by the author and poet Kenji Miyazawa (1896 – 1933), published posthumously. It tells of a boy, with the un-Japanese name of Giovanni, who finds himself atop a starlit hill on the night of the “Milky Way” festival. Down from the heavens comes the wonder train, and Giovanni boards, finding his friend and classmate Campanella already a passenger. The boys in Giovanni’s Island are named in honour of these characters: Junpei for Giovanni and his little brother Kanta for Campanella.

This is a scene from the anime version of Night on the Galactic Railroad. It’s known by variant English names, such as Night of the Milky Way Railway; the Japanese title is Ginga Tetsudo no yoru. The original was a Japanese novella by the author and poet Kenji Miyazawa (1896 – 1933), published posthumously. It tells of a boy, with the un-Japanese name of Giovanni, who finds himself atop a starlit hill on the night of the “Milky Way” festival. Down from the heavens comes the wonder train, and Giovanni boards, finding his friend and classmate Campanella already a passenger. The boys in Giovanni’s Island are named in honour of these characters: Junpei for Giovanni and his little brother Kanta for Campanella.

The cosmic journey in Galactic Railroad interleaves Miyazawa’s devout Buddhism with allusions to contemporary physics, astronomy, paleontology and – perhaps most surprising for Westerners – Christianity. The boys witness shining celestial crosses ringing with “Hallelujah” choruses; they visit a Pliocene coastline to pick million-year-old walnuts, see a puckish bird-catcher snatch herons from heaven, and must finally part on the threshold of a Black Hole.

The anime film, directed by Gisaburo Sugii, is an uncompromisingly stately, poetic and haunting meditation on Miyazawa’s text, which is a study staple in Japan. Reviewers often claim that it’s not a children’s film, but Miyazaki cartoons such as My Neighbour Totoro and Spirited Away – both influenced by Miyazawa’s writing – form bridges to their mystic, melancholy predecessor.

Railroad’s drawing, by the studio Group Tac, is far simpler than Studio Ghibli’s, but the beautiful colour co-ordinations and picture-book look are gracefully self-effacing. What matters is the experience of a child, Giovanni, who barely comprehends the story he’s in. Throughout the film, he moves or is moved through a series of evocative illustrations. On the dark hill where he boards the train, the trees are globular, feminine and mysterious. Later the film’s designs become frightening, with deadly dark water and the bottomless sky-tunnel.

Like Grave of the Fireflies, Railroad was originally written as a requiem for a lost sister, adding resonance to the cartoon’s female imagery. However, the director Gisaburo Sugii, played down the story’s history, saying that he wanted to universalise Miyazawa’s vision. Thus Giovanni and Campanella are drawn as solemn-looking cats (which nicely reflects their uncertain nationality in the story). More than the animation, Giovanni’s character is conveyed by the lucid designs and layouts, and by the melodic transcendence of one of the best scores to ever grace a cartoon.

Giovanni is receptive, sensitive, a chronic outsider. His consciousness is established in the film’s leisurely first third, before he even boards the train. The shadowy, clanking printworks where he runs errands is, for him, a mystical piece of isolated spacetime. Later, taunted by other boys, Giovanni flees the festivities that turn his cobbled town into a citadel of light. The true magic lies in the shadows. Aboard the echoing train, he can only see the wonders from behind a carriage window, and sense an understanding he can’t share between Campanella and the other travellers.

Despite the cornfield and other ecstasies, Giovanni’s journey is one to a mysterious deeper darkness that’s never really broken by the strange lights – the glowing stars, the luminous flowers, the lightbulbs in the train – that limn his journey. For Miyazawa, the dream-odyssey is an inherently moral inquiry, and his thoughts will shock some viewers. At one point, the train turns into a sinking ship (modelled on the Titanic) for a fable about acts, omissions and drowning children. But the film is a call to reconcile love, sacrifice and moral engagement; and it is certainly not a film about suicide, as some books have suggested.

Sugii’s eclectic résumé includes animated versions of the eleventh-century novel Tale of Genji and the arcade game Street Fighter II. The composer was Haruomi Hosono, a sometime bandmate of Ryuichi Sakamoto. The script was adapted by the prolific playwright Minoru Betsuyaku, whose works includes Godot has Come, a comic sequel to Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot. Miyazaki fans may recognise Giovanni’s Japanese voice, actress Mayumi Tanaka, who went on to voice Pazu in Laputa. She’s now voiced Luffy in One Piece for fifteen years.

The image of magic trains, often travelling through outer space or other strange environments, pervades anime. In Ghibli, there’s the haunting image of two ghost children on a train in Grave of the Fireflies, and the train which crosses the sea in Spirited Away. Shinji often finds himself on a dream-train, being interrogated on the state of his soul in the TV Evangelion. Friendlier cosmic trains show up in Welcome to the Space Show and this Hikaru Utada music video by Kazuaki Kiriya (Casshern, Goemon). A Western equivalent is the Christmas-themed Polar Express, and of course there’s Platform 9¾ at Kings Cross.

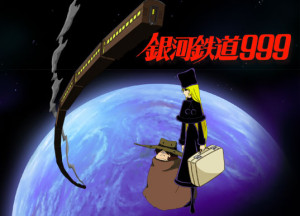

In Japan, the image of a space train was popularised by Miyazawa and by a fantasy forty years later: Galaxy Express 999, by Leiji Matsumoto, which first appeared in manga form in 1977. Whether Matsumoto was influenced by Miyazawa is unclear. In interviews like this one, he said the image came from his own experience of long steam-train journeys through war-blasted Japan. Galaxy Express has far more action and violence than Miyazawa’s creation, but its surreal and spiritual elements put it in the same continuum.

In Japan, the image of a space train was popularised by Miyazawa and by a fantasy forty years later: Galaxy Express 999, by Leiji Matsumoto, which first appeared in manga form in 1977. Whether Matsumoto was influenced by Miyazawa is unclear. In interviews like this one, he said the image came from his own experience of long steam-train journeys through war-blasted Japan. Galaxy Express has far more action and violence than Miyazawa’s creation, but its surreal and spiritual elements put it in the same continuum.

As an anime, Galactic Railroad also has two lesser-known quasi-sequels. The first is Spring and Chaos (1996), sometimes known as Kenji’s Spring. The lavish 50-minute film was directed by Shoji Kawamori, best known as the co-creator of Macross. It’s an impressionistic biography of Miyazawa himself, but it follows the Railroad film by turning the humans into cats, while giant trains blast through the poet’s dreams.

The second film is more notorious, at least for attendees of the Scotland Loves Anime festival. Life of Budori Guskou (2012) was directed by Sugii himself from another Miyazawa tale. The film is set in a parallel world, at first suggesting Grimm fairy tales. Budori is a youth growing up in mountain country. The land is stricken by winter, and his family are cruelly taken, literally in the case of Budori’s kid sister, who’s bundled away by a fearsome spirit-cat. But then the film shows Budori and the other characters as cats too.

Guskou became a standing joke at Scotland Loves Anime and the jeers are mostly justified. The film is excruciatingly slow and seemingly pointless. We follow Budori through random-seeming episodes, planting crops in rice fields or conducting science projects in a steampunk city, all monorails and clockwork planes. Despite the frequently lovely images, all involvement with the film evaporates, leaving the average viewer gasping for it to stop. (At the SLA screening I attended, there was a groan of relief as the end credits rolled.)

Guskou became a standing joke at Scotland Loves Anime and the jeers are mostly justified. The film is excruciatingly slow and seemingly pointless. We follow Budori through random-seeming episodes, planting crops in rice fields or conducting science projects in a steampunk city, all monorails and clockwork planes. Despite the frequently lovely images, all involvement with the film evaporates, leaving the average viewer gasping for it to stop. (At the SLA screening I attended, there was a groan of relief as the end credits rolled.)

And yet the film’s a bit more bearable if you watch it after Galactic Railroad, which intersects with Budori Guskou with glimpses of its characters and its brilliance. One freaky sequence in the latter film, involving endless ladders and silkworm cocoons, may burrow into kids’ imaginations in the manner extolled by Giovanni’s Island. If you liked Railroad, you’ll be less fazed by Budori’s sluggish pace and reality shifts, and its sheer oddness makes it an interesting disaster, at least.

Andrew Osmond is the author of 100 Animated Feature Films. Giovanni’s Island is available on UK DVD and Blu-ray from Anime Ltd.

anime, books, giovanni's island, Japan, Kenji Miyazawa, Night on the Galactic Railroad, Night Train to the Stars

J.R.D.S.

January 24, 2019 8:48 am

Given all that's written above, why are Anime Limited then releasing Giovanni's Island and not Night on the Galactic Railroad? The article is an extremely good advertisment for the latter – until one gets to the end and it then tells me only how I can see a different film than the one it's been making you enthralled with the idea of experiencing.