Hokusai’s Tentacles

July 14, 2015 · 0 comments

By Ellis Tinios.

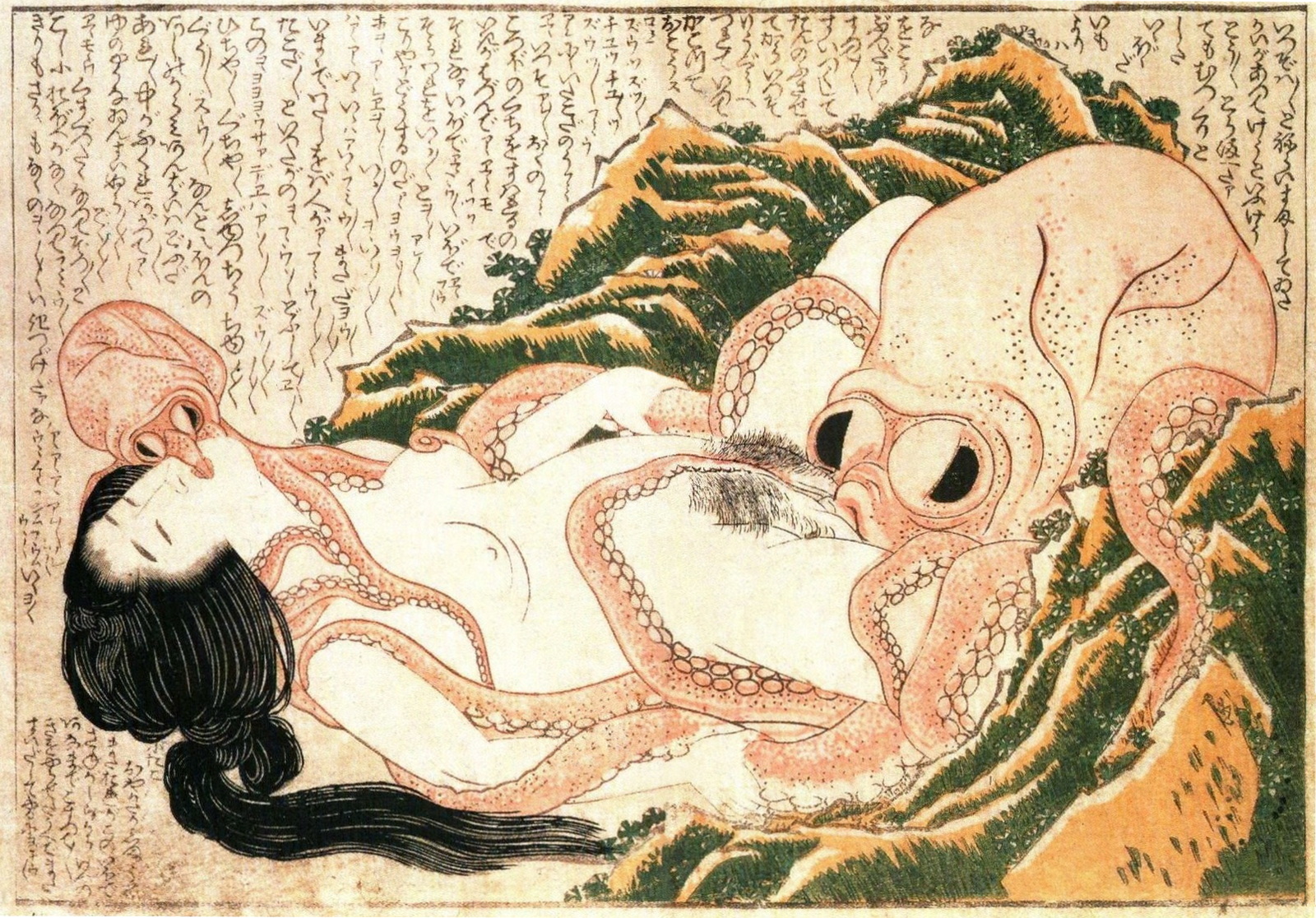

Under the sea a living woman — full-bodied and entirely naked — lies back amid rocks. A large octopus is pressing his beak into her crotch. One of his tentacles has moved under her thigh and up across her belly, parting her pubic hair. He has entwined other tentacles around her arms and right shoulder to draw her closer to him. The woman responds by half-closing her eyes and throwing back her head in pleasure. At the same time, she grasps firmly onto two of his tentacles with her hands in a gesture devoid of any suggestion of resistance. A smaller octopus fastens onto her mouth with his beak, coils the tip of one tentacles around her left nipple while extending others around her neck to embrace her.

When this untitled image — a double-page spread in a colour woodblock-printed erotic book illustrated by Hokusai — arrived in Paris in the 1870s it shocked and thrilled collectors, connoisseurs and writers on the art of Japan. For well over a century it was the subject of intense scrutiny and feverish speculation. Many readings were imposed on it: terrifying nightmare; repellent violation; macabre fantasy; lurid rape. Whatever the interpretation they imposed on it, the commentators all agreed that it was an extraordinary manifestation of Hokusai’s fecund imagination. They praised it as an image without precedent in Japanese or world art. These fantasists were wrong in their readings of the scene and their claims that it lacked precedent. The image represents a woman enjoying exquisite sexual pleasure and has clear precedents in Japanese art. The key to the image lay in the lengthy text that fills the entire background. Generations of Western commentators, confronted with a text they could not decipher, simply ignored it, erased it from their discussion of the the image with which it was inextricably linked. They behaved as thought the scene were being enacted against a blank ground even though artist and author collaborated closely to produce a coherent and satisfying conjunction of text and image.

As noted by Danielle Talerico, in ‘Interpreting Sexual Imagery in Japanese Prints: A Fresh Approach to Hokusai’s Diver and Two Octopi’ in Impressions: The Journal of the Ukiyo-e Society of America (from which all translations in this article come), the text, in vertical columns, moves from right to left across the double-page spread. It presents the thoughts and words of the three participants interrupted by transcriptions of the slurping and sucking sounds being made by the two octopuses and the pleasurable exclamations their actions elicit from the woman. The woman describes her feelings of mounting pleasure as her body and limbs are entwined and caressed by the tentacles and the larger octopus penetrates her vagina. Her climax is made explicit: “One after another until I lose track fu, fu, fu, fuu, fuu, limits and boundaries are gone oo, oo, oo, I’ve arrived anna, aaaaaa, there, there, here, here, uu, mu, mu, mu, fun, mufu, umu,uuuuu, good! Good!”

The larger octopus is a connoisseur, commenting: “…this is a plumb, good pussy.” The smaller one, his son, is eager to take his father’s place, boasting that he will stimulate the woman to such a pitch that she “loses consciousness, [and] when she revives, I’ll do it again…”

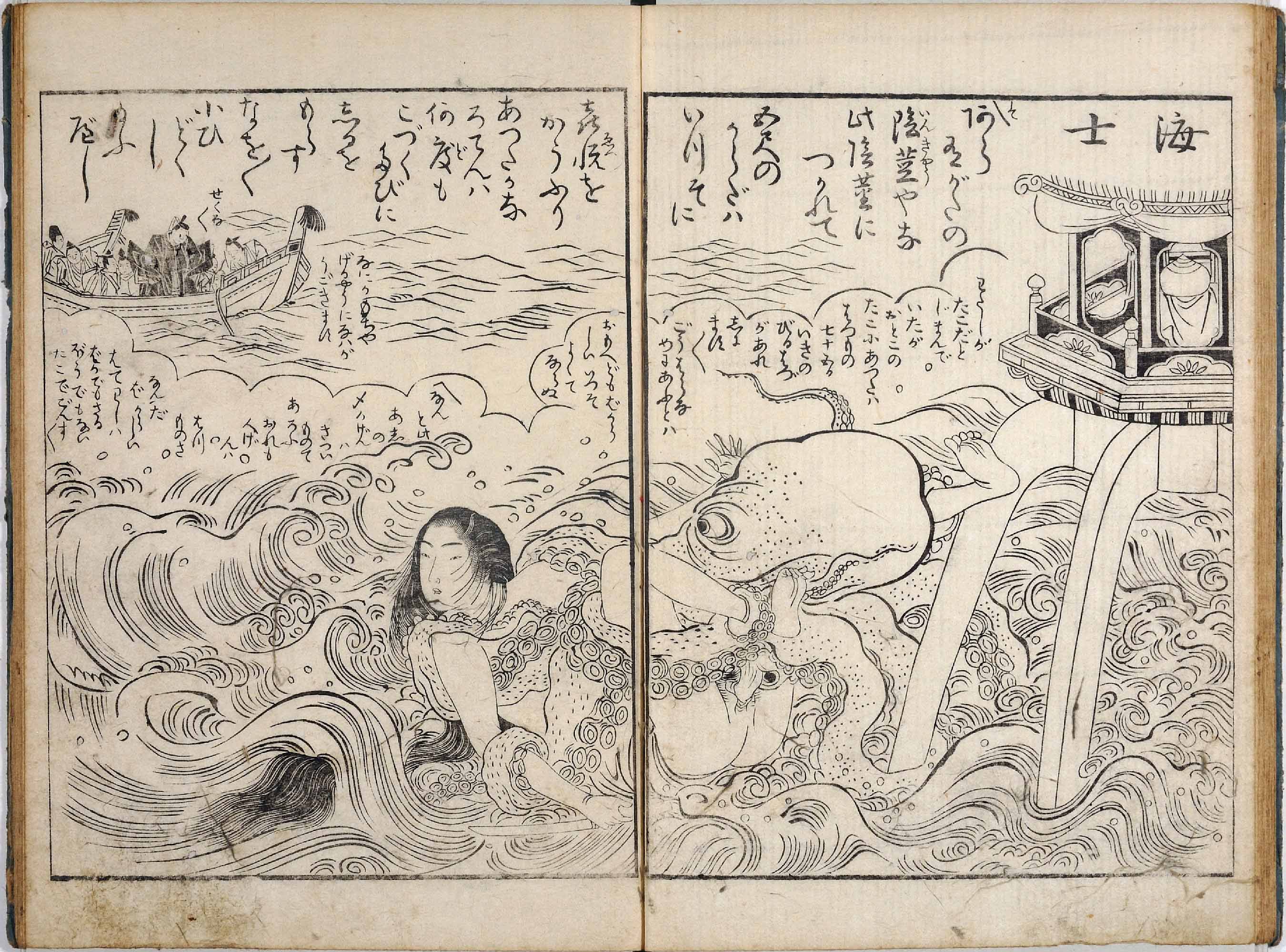

Hokusai’s print is a parody that references the Tamatori (Jewel Thief) story. A jewel sent from China to Japan to grace a newly built Buddhist temple was stolen enroute by the Dragon King of the Sea. A diver woman married to a courtier seeks to retrieve the jewel for her husband. (The circumstances leading to this marriage of social unequals need not be retold here.) She is detected in the undersea palace of the Dragon King and flees with the jewel pursued by various sea creatures. Realising that she cannot escape her pursuers, she slits open one of her breasts and secretes the gem in the wound. Her dead body is retrieved, the jewel found and ensconced in its proper place. In 1781 Kitao Shigemasa included a parody of the story in the three-volume erotic book Yōkyoku iro bagumi (Erotic programme of Noh Librettos). He references the Noh theatre version of the story, a play entitled Ama (Diver) Hokusai is likely to have known this design when he created the image under discussion here for inclusion in the erotic book Kinoe no komatsu (Young pine saplings), which was published in three volumes in 1814. This is the only fantastic coupling in the book. Dominant women predominate in it, women taking the initiative with their partners and thoroughly enjoying the pleasure of intercourse — as the woman does here. A line in the text links the image firmly to the jewel thief story. The larger octopus says that after ‘…sucking to complete satisfaction, then to take her to be imprisoned in the Dragon King’s palace.”

Women divers were a favorite subject for ukiyo-e artists. Utamaro, the great master of the female image, produced memorable colour woodblock prints in which he presents them as objects of sexual desire. It is not surprising that they are also appear in sexually explicit books. The coupling of a woman diver with an octopus is, however, an unexpected development. There are rare instances of a woman depicted mounted by a dog (the result being the Eight Dog Heroes, subjects of popular novels and plays as well as erotic books, a.k.a. The Hakkenden), even rarer instances of intercourse with a stallion. The octopus is the rarest of all non-human partners. Only an artist of Hokusai’s calibre could create such a compelling image of this most extraordinary scene. Just as Hokusai’s Great Wave print is the best known of all Japanese colour woodblock prints, so too, this image is the widest known of all Japanese erotic images.

Ellis Tinios is the author of Japanese Prints: Ukiyo-e in Edo 1700-1900, available now from the British Museum Press.

Miss Hokusai will be released by Anime Ltd as an Ultimate Edition Blu-ray/DVD set as well as on Blu-ray and DVD from 14th November 2016.

Leave a Reply