Lupin the 3rd: Part IV

May 16, 2018 · 0 comments

By Andrew Osmond.

Some pop-culture heroes only live twice. Others survive through endless reboots, re-imaginings and re-brandings, until they’re barely recognisable if you knew the originals. Japan’s Lupin the Third is different. He’s been in anime nearly fifty years, and yet you could show the new Lupin TV series, being released by Anime Limited, to a Japanese person of pretty much any generation and get a nod of recognition. Lupin may change his jacket occasionally – in this series, it’s blue – and his voice may not sound quite the same. But otherwise he’s as unchanging as Mickey Mouse or Bugs Bunny, if Mickey and Bugs were career criminals, drove fast cars, and had an insatiable appetite for the ladies.

Some pop-culture heroes only live twice. Others survive through endless reboots, re-imaginings and re-brandings, until they’re barely recognisable if you knew the originals. Japan’s Lupin the Third is different. He’s been in anime nearly fifty years, and yet you could show the new Lupin TV series, being released by Anime Limited, to a Japanese person of pretty much any generation and get a nod of recognition. Lupin may change his jacket occasionally – in this series, it’s blue – and his voice may not sound quite the same. But otherwise he’s as unchanging as Mickey Mouse or Bugs Bunny, if Mickey and Bugs were career criminals, drove fast cars, and had an insatiable appetite for the ladies.

Lupin is theoretically a master criminal, but really he’s a showman and show-off. He just loves pulling off impossible crimes from under the noses of authority, treating the world as one giant piggy-bank begging to be smashed. He’s cool and clever, childish and fallible. You could play a drinking game based on Lupin’s face-drops every time something doesn’t go to plan; and another for when he bounces back at Mach 5. He’s also a magician of disguise and impersonation, as demonstrated many times through the new series.

You don’t need to know any of Lupin’s hundreds of capers through the decades in manga and anime, though there’s a history of the franchise here. All you really need to know is that Lupin has four unshakeable hangers-on. Jigen is a gangster-style sharpshooter who’s Lupin’s closest confidante. Goemon is an honest-to-goodness master samurai, known to slice helicopters and missiles with his immaculate blade. Fujiko is the Catwoman to Lupin’s battiness, sometimes his rival, sometimes his girlfriend, but always the woman he can’t master. And then there’s Inspector Zenigata, the policeman forever trying to bring Lupin down, despite his decades-long perfect fail rate.

Viewers are likeliest to know two takes on Lupin. One is 1979’s Castle of Cagliostro, the first cinema film by Hayao Miyazaki. He envisioned Lupin as practically a romantic hero in a Ruritanian swashbuckler, inspired by Prisoner of Zenda; the film’s long enshrined as a classic of anime. The other incarnation is 2012’s The Woman Called Fujiko Mine, which was less a TV series than an animated art installation. Amid its gorgeously stylised graphics, Lupin and the other males played second fiddle to Fujiko, elevated to her zenith as a slinky sex goddess. Two of that show’s creators were women, director Sayo Yamamoto (Yuri on Ice) and lead writer Mari Okada (Maquia), while the character design and animation direction was handled by Takeshi Koike (Redline).

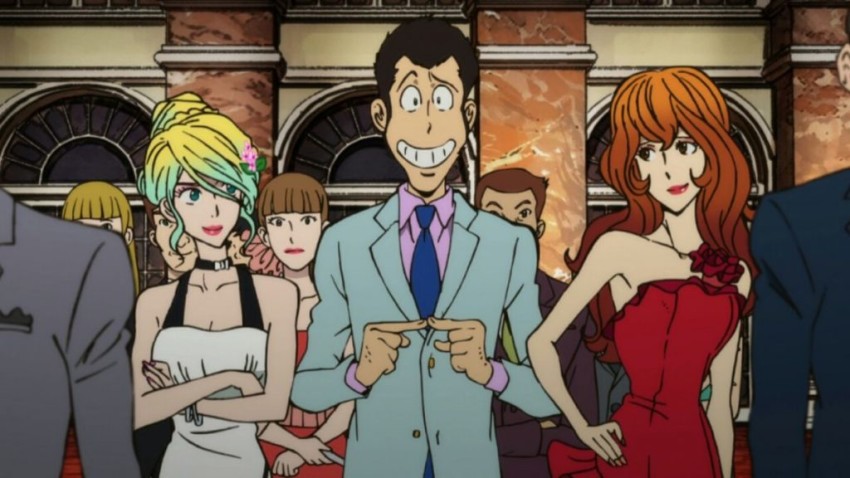

Fans may argue that neither of these versions were the “real” Lupin, but frankly, if the character wasn’t stretchy enough to accommodate both, he wouldn’t have lasted this long. The series being released by Anime Limited is a far more mainstream Lupin than Fujiko Mine, with the sex and artiness toned right down. But it’s far from franchise hackwork. It’s extraordinarily good-looking, full of popping bright colours and bold, frame-filling characters, and a Lupin brimful of masculine confidence and crooked charisma.

Fans may argue that neither of these versions were the “real” Lupin, but frankly, if the character wasn’t stretchy enough to accommodate both, he wouldn’t have lasted this long. The series being released by Anime Limited is a far more mainstream Lupin than Fujiko Mine, with the sex and artiness toned right down. But it’s far from franchise hackwork. It’s extraordinarily good-looking, full of popping bright colours and bold, frame-filling characters, and a Lupin brimful of masculine confidence and crooked charisma.

This is a Lupin for the world market, as confirmed by one of the most unusual things about it. Its TV premiere wasn’t in Japan, but in Italy, on the Italia 1 channel. The Italian version had an entirely different theme song, performed by the rapper Moreno. Indeed, the series is mostly set in Italy, though the very first episode opens in the tiny picturesque “microstate” of San Marino; for anyone wondering if it’s invented like Miyazaki’s Cagliostro, it’s entirely real. Lupin has always been a citizen of the world, and his show’s cast, Lupin himself included, look neither particularly Japanese (Goemon excepted) nor like 21st-century anime. It would be interesting to know if some of the young Italian viewers watching Lupin on TV didn’t register its Japanese-ness at all, like the “hidden import” anime of past decades.

Promoting the new series, director Kazuhide Tominaga said he wanted “to depict a Lupin in which conflicting elements coexist – hard-boiled yet comical, cool yet tongue-in-cheek.” That mix is clear from the early episodes. They’re often whimsical and silly, and some upfront elements seem to deliberately evoke the (relatively) gentle Lupin of Cagliostro. The show starts with a wedding ceremony that’s wildly disrupted by the Lupin characters, echoing the climax of Miyazaki’s film, though this time the groom is Lupin himself. The third episode actually works in a reference to “Cagliostro” – not the Miyazaki villain, but the historic “Count Cagliostro”, aka Giuseppe Balsamo.

But the third episode also brings in the hard-boiled elements Tominaga mentioned. We see Lupin’s comrade Jigen luridly tortured by electrocution. His interrogator/torturer is a certain British MI6 agent whom we soon learn has a licence to kill. He doesn’t just resemble James Bond, but specifically Daniel Craig’s James Bond, already well-established when this Lupin was made. It’s a nod to Lupin’s roots. Bond is widely seen as one of Lupin’s chief inspirations back in the 1960s, an icon of masculine wish fulfilment (action, sex, style). But the series also points up how different the characters are when they come together. The British gentleman killer is set against the rubbery Japanese clown.

But the third episode also brings in the hard-boiled elements Tominaga mentioned. We see Lupin’s comrade Jigen luridly tortured by electrocution. His interrogator/torturer is a certain British MI6 agent whom we soon learn has a licence to kill. He doesn’t just resemble James Bond, but specifically Daniel Craig’s James Bond, already well-established when this Lupin was made. It’s a nod to Lupin’s roots. Bond is widely seen as one of Lupin’s chief inspirations back in the 1960s, an icon of masculine wish fulfilment (action, sex, style). But the series also points up how different the characters are when they come together. The British gentleman killer is set against the rubbery Japanese clown.

From then on the show swings, like Bond, from dark to daft. Several episodes select one of Lupin’s supporting cast to put centre stage. For example, the gunslinger Jigen is placed in a neo-Western yarn, set in a ghost town where his miracle shooting is tested. Another episode, especially interesting, focuses on the policeman Zenigata protecting a billionaire’s widow. This story goes where most Western scriptwriters would fear to tread, with underage sex victims and (ostensible) male saviours. But the story has multiple twists, and an ending that suggests that Lupin, like some later 007 films, is trying to move with changing attitudes. Even if you hate this episode, and some viewers will, it’s still fascinating to see what a “lightweight” franchise show can try.

The episode also stresses the honour of Inspector Zenigata, after the rather shocking treatment of the character in The Woman Called Fujiko Mine. Zenigata’s also central to a later episode, where – minor spoiler – Lupin is incarcerated, and Zenigata becomes his paranoid guard, unable to believe his nemesis would give up so easily. The episode reworks one of the oldest Lupin manga stories, “The Great Escape,” first animated in a 1971 TV series, though the new version has a different, less brutal punchline.

On the other hand, the new series takes a trick from The Woman Called Fujiko Mine. While many of the episodes are episodic romps, it also has an arc storyline that’s only revealed in the later episodes. This turns out to be preposterous sci-fi, in the mould of the fondly-remembered 1978 Lupin movie The Secret of Mamo. Tominaga, Chief Director of the new series, first cut his teeth as a Mamo animator.

In such ways, the series acknowledges its multi-faceted heritage. But it’s also keen to bring in new elements, with two characters that don’t appear in every story, but recur through the series. We’ve already mentioned one of these characters, the Bond-ish British agent, who’s codenamed Nyx. In a twist on expectations, we later learn that Nyx is a devoted family man; his homicidal protective instincts suggest the writers have watched Taken.

In such ways, the series acknowledges its multi-faceted heritage. But it’s also keen to bring in new elements, with two characters that don’t appear in every story, but recur through the series. We’ve already mentioned one of these characters, the Bond-ish British agent, who’s codenamed Nyx. In a twist on expectations, we later learn that Nyx is a devoted family man; his homicidal protective instincts suggest the writers have watched Taken.

The other character, more potentially controversial with long-time Lupin fans, is Rebecca Rossellini, who’s marrying Lupin in the first episode. Introduced as a seemingly air-headed goodtime gal, she’s swiftly revealed to be another thrill-seeking criminal. This puts her into competition with Lupin and also Fujiko, the franchise’s established femme fatale. As with pitting Lupin against Nyx, the strategy is to set established characters against variants of themselves. Rebecaa is cute and kittenish, far less mature than the sultry Fujiko, but again the show’s no slave to anime fashions. There’s nothing moe about Rebecca; she may have a loyal manservant, but sees men as Fujiko does, as playtime. Her love-rivalry with Fujiko is a passing gag, with a palpable sisterhood between them.

Rebecca’s voiced in Japanese by Yukiyo Fuji, whom readers may recognise as the upside-down heroine in Patema Inverted. Meanwhile, the main cast are old Lupin hands. Kanichi Kurita has been played the title thief since 1995, when the original Lupin actor (Yasuo Yamada) passed away. Daisuke Namikawa as Goemon joined the franchise in 2011, as did Miyuki Sawashiro (Celty in Durarara!!) as Fujiko. So did Koichi Yamadera as Zenigata; he was already famous as Spike in Cowboy Bebop, a melancholy riff on Lupin’s basic set-up.

However, the voice-actor for the gunslinger Jigen, Kiyoshi Kobayashi, goes all the way back. Now an octogenarian, Kobayashi first voiced Jigen in 1971, in the first Lupin TV series, and he’s been in almost every Lupin since then. That includes not only the thief’s Italian caper, but the follow-up series which came to TV this year. It’s set in France, where Lupin now wields mobile phones as deftly as his trusty Walter P38. He’s still a citizen of the world, and a thief for all times.

Andrew Osmond is the author of 100 Animated Feature Films.

Lupin III: Part IV is released in the UK by Anime Limited.

Leave a Reply