10 Years with Hayao Miyazaki

March 7, 2022 · 0 comments

By Helen McCarthy.

There are many ways to explore and interrogate an artist’s work. One is through experiencing and analysing the work itself. Another is through contact with the artist, through their recorded or published words or in a face to face interview. One can also look at what others – friends, enemies, competitors, critics, scholars – have said or written about them and their work. Kaku Arakawa’s documentary series for NHK World TV chooses to focus mainly on direct recording of Hayao Miyazaki’s own words and actions, and his interactions with a few of those around him in his day-to-day context.

When dealing with genius – and Hayao Miyazaki is demonstrably a genius – documentary can slide into hagiography. Full disclosure: I share responsibility for the now extensive English-language Miyazaki hagiography industry, having written the first English book devoted to his work in 1999. When an artist has legions of devoted fans all over the world, challenge and deconstruction isn’t necessarily what they want to see.

The Miyazaki legend makes hagiography hard to avoid, especially in the West where the range of media critique is relatively limited. The image of the driven creative genius turning out film after film of a beauty rarely matched and never surpassed is not only true, but also managed by one of the most gifted and unobtrusive fixers in the movie business, Studio Ghibli’s former president, now general manager and long-time producer Toshio Suzuki. Suzuki’s light but unerring touch has steered the studio through its four-decade climb to global prominence. The foregrounding of Miyazaki’s individual genius, which plays so well alongside American animation’s core hagiography of Walt Disney, has highlighted Ghibli’s unique status as a distant temple of animation, the tori gate at the peak of the mountain from which film after perfect film emerges.

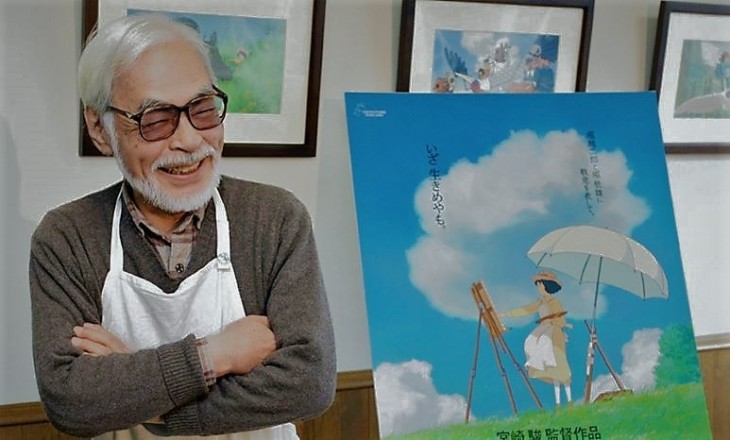

Any documentary on Hayao Miyazaki has to reckon with a formidable precursor: Mami Sunada’s Kingdom of Dreams and Madness, a 118-minute film released in 2013. Sunada tracked the progress of the studio and its two principal directors over a year in which it worked on two major productions at once, Miyazaki’s The Wind Rises and Isao Takahata’s The Tale of the Princess Kaguya.

At this point, Arakawa was also filming at Studio Ghibli, approaching the end of a ten-year process for NHK TV documenting Miyazaki’s working life. Arakawa had access under the same conditions as Sunada – one person with one camera to film and conduct interviews. The result was a TV mini-series aired six years later, in 2019. Such a lengthy editing process suggests difficult choices from a mass of material.

There are many frustrations for me, and I suspect for other Ghibli fans and scholars, in this interesting series. Some may arise from NHK’s requirements. I suspect the background music, which I find mostly irritating, is one such. But even four hours is very little time to show ten years of filming, and it’s infuriating to see a number of repeated shots and sequences. I want to raid Arakawa’s editing suite and see the deleted footage. The lack of a clear flow of time can also be confusing; Arakawa takes a thematic rather than a linear approach to his story But there’s no point reviewing the film the director didn’t make. The one he did has much to offer.

Arakawa looks closely at Miyazaki’s everyday process, prioritising his domestic routine and his relationship with his work, editing his interactions. Five decades of friendship with Ghibli’s colour designer Michiyo Yasuda is pictured affectionately; she goes with him to the first screenings of his son Goro’s films. Yet there’s no mention of Isao Takahata, director and producer at Studio Ghibli, his senior at Toei Animation and his colleague for even longer than Yasuda, until he becomes dramatically necessary halfway through the series. Miyazaki is mired in uncertainty as he develops The Wind Rises. Then, at the studio end-of-year party, he learns from Suzuki that Takahata is also working on a new film. This perfect timing re-energises Miyazaki to push ahead, and Takahata steps back into the shadows. This isn’t his story.

The deployment of this moment, its timing within the flow of the series, also points up the importance to the documentary film-maker of leaving unsaid things that engage the viewer afterwards. Why was Takahata, famously even more stubborn and determined than Miyazaki, not at the office party? That and a number of other questions and connections arising from the footage are, for me, the real treasures of 10 Years with Hayao Miyazaki.

In many ways, Suzuki’s brief appearances in Arakawa’s film are the most revealing. It’s Suzuki who steers relationships and calms ruffled waters. At a meeting to select voice actors for audition, Miyazaki is adamant about the qualities he wants in the voice of Jiro. It’s Suzuki who suggests, casually, that “an amateur may be a better fit” and that Miyazaki’s friend and protégé Hideaki Evangelion Anno should audition for Jiro’s voice for The Wind Rises. Miyazaki is obviously delighted. After Anno’s voice test he races round the studio telling everyone the news that his friend has the role. This points yet again to Suzuki’s understanding of the man he’s worked with for so many years.

Arakawa gives us a new angle on the process of succession planning at Ghibli, with much time devoted to the highly publicised dissension and reconciliation between Miyazaki and his son Goro over the course of Goro’s two films as director at Ghibli. No new or shocking revelations emerge, but Arakawa shows empathy with Goro, using up precious airtime to present his journey and his relation to his father as an artist in a more nuanced and extensive way than in Sunada’s documentary.

There are some revealing childhood photographs in the footage, including one of toddler Hayao with his mother, and several with his father and three brothers. There’s footage of drawings he made of Goro in childhood, but no mention of his younger son Keisuke, a printmaker who has himself been the subject of exhibits and celebrations in his own field, who presumably lived with the same paternal absences as Goro. The film sticks firmly to Miyazaki in his working context. Anything unconnected with that is omitted, but within this narrow frame we see the constant mood shifts, uncertainties, experiments, self-encouragement and self-castigation that drive Miyazaki’s process.

Miyazaki is seen chatting about the death of the great animator Reiko Okuyama, a colleague at Toei Animation in his early years in the business, and at a memorial service for director Umanosuke Iida, his assistant director on Castle in the Sky. Okuyama was five years his senior, Iida twenty years his junior, yet he seems as surprised to have survived her as sad to have survived Iida. Mortality is much on his mind as he contemplates the loss of colleagues, but when the Great East Japan Earthquake strikes in 2011 he refuses to close the studio, saying that it’s precisely at such times they should make films. He focusses on helping the survivors with a morale-raising visit to devastated areas and, of course, by forging ahead to make films that people will enjoy.

The examination of Miyazaki’s working process is close, but without exploring the works themselves. In the first episode, we see a telling piece of preparatory work for Ponyo: an image board showing Ponyo still in her juvenile form as a human-faced fish, riding on top of a giant jellyfish while peeping from beneath another, smaller jellyfish. To me, this echoes images from Nausicäa of the Valley of the Wind showing the heroine atop the empty carapace of a gigantic insect under a smaller clear dome, one of its eye-cases. The jellyfish are as key a part of Ponyo’s journey as the Ohmu are of Nausicaä’s. We see footage of Miyazaki working on storyboards for The Wind Rises and discussing the importance of Jiro’s struggle to create the Zero fighter. But Arakawa doesn’t mention Miyazaki’s family connection with the Zero fighter – his father worked for the family company, Miyazaki Airplane, making Zero fighter parts. Analysis and speculation is not Arakawa’s chosen path. He presents his material and leaves the viewer to make their own connections.

Arakawa’s film concludes with the news of another of Miyazaki’s official retirements. This one too didn’t last. He’s currently working on a new film due in 2023, pursuing the question he asks frequently in the course of Arakawa’s filming: how does one live fully in difficult times?

Goro made a third film at Studio Ghibli, released in 2020. Michiyo Yasuda died in 2016 aged 77. Isao Takahata died in 2018. But before that, Arakawa spent ten years recording daily life in Miyazaki’s changing, challenging, vanishing world. That he didn’t tell us everything about that world doesn’t make his work any less evocative, or less poignant.

10 Years with Hayao Miyazaki is released on UK Blu-ray by Anime Limited. Helen McCarthy is the author of Hayao Miyazaki: Master of Japanese Animation.

Leave a Reply