Books: Ghost in the Shell

November 29, 2017 · 0 comments

By Jasper Sharp.

The Paramount live-action remake of Ghost in the Shell (1995) arrived with much fanfare and more than a little controversy earlier this year. Andrew Osmond’s pocket-guide companion to the anime original was initially intended to arrive in time to capitalise on its success, although for various reasons, the publication was held up until September. Not that this is much of an issue: “success” might not be a word one might readily apply to Rupert Sanders’ American film.

The Paramount live-action remake of Ghost in the Shell (1995) arrived with much fanfare and more than a little controversy earlier this year. Andrew Osmond’s pocket-guide companion to the anime original was initially intended to arrive in time to capitalise on its success, although for various reasons, the publication was held up until September. Not that this is much of an issue: “success” might not be a word one might readily apply to Rupert Sanders’ American film.

There might be any number of reasons for this relative box-office failure. Few in the online community will be unaware of the accusations of white-washing surrounding the casting of Scarlett Johansson as the cyborg protagonist Major Motoko Kusanagi. A more convincing explanation is that Paramount simply overvalued the cultural capital of Mamoru Oshii’s original adaption of Masamune Shirow’s manga. Ghost in the Shell might well be a touchstone in the world of anime fandom, but it seems the average movie-goer didn’t have quite the same emotional connection to the source material.

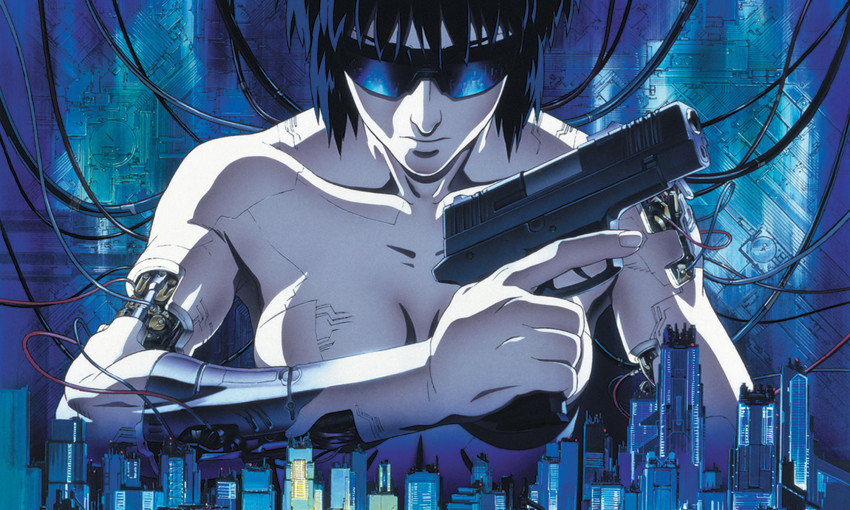

With its detailed graphic style, dystopian vision and esoteric musings, Oshii’s film set jaws dropping when it first appeared in front of Western viewers. There was simply nothing else like it. Now its pioneering thematic and philosophical elements have been so assimilated into the mainstream (and let’s face it, Oshii himself has admitted more than a little of his own debt to Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner) that there was precious little in promotional terms to distinguish the remake’s take on the material from any other big-budget Hollywood sci-fi.

With its detailed graphic style, dystopian vision and esoteric musings, Oshii’s film set jaws dropping when it first appeared in front of Western viewers. There was simply nothing else like it. Now its pioneering thematic and philosophical elements have been so assimilated into the mainstream (and let’s face it, Oshii himself has admitted more than a little of his own debt to Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner) that there was precious little in promotional terms to distinguish the remake’s take on the material from any other big-budget Hollywood sci-fi.

Osmond fascinatingly details Ghost’s unusual emergence into global consciousness. The project owes a large part of its genesis to the British company Manga Entertainment, the brainchild of a former marketing manager and director at Island Records named Andy Frain, who is credited as one of the film’s executive producers. By the mid-1980s, the label’s founder Chris Blackwell had hit upon the idea of moving into producing and marketing original “finished-package goods” specifically for the emerging home video market, originally focussing on music videos. When Island Records was sold to Polygram in 1989, Blackwell set up a new company, Island World Communications, bringing Frain onboard with him, but the Polygram deal effective barred the company from any music-related projects.

Frain saw Katsuhiro Otomo’s Akira in 1991 and “… started thinking this was more than a great film. This might be a phenomenon. Were there more films like this in Japan?” Otomo’s film was released by Island World, but for their next acquisitions, the company founded the Manga Entertainment sub-label. Of course, we all know the difference between manga and anime nowadays, but at the time, it was still a new, exciting and exotic word in the English language.

As Osmond points out, “For readers who’ve grown up with anime of all kinds, from Dragon Ball to Death Note, Pokemon to Spirited Away, it may be hard to imagine how new Akira felt in its day.” Nevertheless, Manga Entertainment effectively “began as a marketing concept in search of content” – the truth, as we now know, was there simply weren’t that many films of the same quality and ambition in Japan in the late-1980s and early-1990s, not ones within the budget of a relatively small outfit catering for an embryonic market. And so, after a handful of generally lesser releases, of which Legend of the Overfiend is the most notorious example, Frain approached Kodansha, the publisher of Masamune Shirow’s manga, with the idea for a co-production, eventually stumping up about a third of Ghost in the Shell’s £2.5 million budget.

While Manga Entertainment had released the anime adaptions of Shirow’s Dominion (1988) and Appleseed (1988), at this point Oshii was an unknown quantity in the West. His aesthetic and thematic precursors to Ghost in the Shell, the Patlabor video series (1988-89) and two theatrical spin-offs (from 1989 and 1993 respectively) had yet to be released outside Japan. Oshii was actually roped into the project after going to visit the Bandai production company to pitch his script for a film that would be later made by Hiroyuki Okiura as Jin-Roh: The Wolf Brigade (1999). Instead, the Bandai producer thrust a copy of Shirow’s manga into his hands, ordering him “You do this.”

According to Oshii, Manga Entertainment’s input in shaping the finished film was negligible, as indeed was that of Shirow, who kept his distance after more than a few unhappy experiences with the anime world, not the least his co-direction credit on the 45-minute Black Magic M-66 (1987) with Hiroyuki Kitakubo, not to mention disappointing earlier adaptations of his work.

“Masamune Shirow was a nice guy”, Osmond reports Oshii saying. “Because I only saw him once, I didn’t fight with him.” The destruction of the Kobe-based manga artist’s home in the Great Hanshin earthquake of 1995, at the time Ghost was being made, also played a fairly substantial part in this absence from the production.

Comparing the anime with the manga source material, Osmond notes a number of alterations and additions made by Oshii, notably the director’s trademark biblical allusions. He also delves much deeper into the production history, providing information on all those involved in making Ghost such a unique experience, from screenwriter Kazunori Ito, composer Kenji Kawai and the animation team at Production I.G to the voice actors of both the Japanese version and the English dub. Oshii’s career is detailed, and a fairly exhaustive synopsis also included. Osmond also explores the connection with Blade Runner and William Gibson’s classic of cyberpunk literature, Neuromancer (1984). There’s also information about the film’s sequel, the Stand Alone Complex TV series from 2002, and the digitally embellished version that appeared in 2008 as Ghost in the Shell 2.0.

Comparing the anime with the manga source material, Osmond notes a number of alterations and additions made by Oshii, notably the director’s trademark biblical allusions. He also delves much deeper into the production history, providing information on all those involved in making Ghost such a unique experience, from screenwriter Kazunori Ito, composer Kenji Kawai and the animation team at Production I.G to the voice actors of both the Japanese version and the English dub. Oshii’s career is detailed, and a fairly exhaustive synopsis also included. Osmond also explores the connection with Blade Runner and William Gibson’s classic of cyberpunk literature, Neuromancer (1984). There’s also information about the film’s sequel, the Stand Alone Complex TV series from 2002, and the digitally embellished version that appeared in 2008 as Ghost in the Shell 2.0.

Ghost in the Shell was always conceived with an overseas audience in mind, but whether at home and abroad, this audience was considered a niche one. The film enjoyed only a two-week run in Japanese cinemas upon its released in November 2005, while its North American theatrical took just half a million dollars, playing mainly at arthouse venues. It faired far better on home video, however, topping the Billboard sales chart and going on to sell over a million copies before the release of Oshii’s much bigger-budgeted sequel Ghost in the Shell 2: Innocence in 2004. It is certainly a watershed title in anime history that has become firmly ensconced as a cult favourite, but when you consider the Hollywood remake has currently taken over $160 million, it is fair to say one is not comparing like with like.

And this brings us to the thorny issue of white-washing, which Osmond inevitably raises although slightly brushes aside as “outside the remit of this book”. My own feeling is that the underrepresentation of Asians in Hollywood cinema is certainly a valid issue that needs addressing, but that Ghost in the Shell is perhaps not the best target. The argument put forward by many – that this is a Japanese story, set in Japan, and therefore must have a Japanese actress as Major Kusanagi – doesn’t really wash, in that the film explicitly addresses such themes as the blurred boundaries between the real and the virtual, the human and the post-human, and the complete breakdown of national borders, by its very use of animation, a medium is intrinsically unreal, for all Oshii’s attempts at realism (these ideas are dealt with in an even more sophisticated fashion in the sequel).

As Osmond points out, there’s nothing within the film itself that specifies identifies Newport City, where the action unfolds, as being in Japan. In fact it was modelled on Hong Kong, and Oshii himself is quoted as saying “If you think about Hong Kong, you imagine a city teeming with information… There are countless signs and a cacophony of voices which flow through the city.” Art director Hiromasa Ogura worked on photos he’d taken of Kowloon Walled City, before the area was demolished in 1993, for the backdrops, and the characters on the background signs are actually written in Chinese, not Japanese – something that would have been readily apparent to local viewers.

As Osmond points out, there’s nothing within the film itself that specifies identifies Newport City, where the action unfolds, as being in Japan. In fact it was modelled on Hong Kong, and Oshii himself is quoted as saying “If you think about Hong Kong, you imagine a city teeming with information… There are countless signs and a cacophony of voices which flow through the city.” Art director Hiromasa Ogura worked on photos he’d taken of Kowloon Walled City, before the area was demolished in 1993, for the backdrops, and the characters on the background signs are actually written in Chinese, not Japanese – something that would have been readily apparent to local viewers.

Moreover, the character played by Johansson is not only a cyborg, but she doesn’t actually own her own body – it belongs to the government. Only her consciousness is human, hence the title. Whether she appears “Japanese” or not in the manga or anime is a moot point, because in organic terms, she isn’t. Anime characters are, in general, drawn as racially indeterminate, but in the film Kusanagi actually has blue eyes, and the supporting characters of Bateau and Togusa certainly appear more Caucasian than Asian. An interesting and not entirely unrelated fact is that the voice artist who plays Bateau, Akio Ohtsuka, also provided the vocals for Samuel L. Jackson in the Japanese dub of Pulp Fiction, perhaps adding a further level of complexity to the race issue. Essentially what Oshii is doing in his film is foregrounding these issues of reality, materiality, aesthetics and perception using the animated medium in his two Ghost films, and Johansson’s own body is heavily CG-augmented in the “live-action” version. There may be a host of reasons why it would have been nice to have an Asian actress in the role, but there’s nothing in the original source that says this has to have been the case.

Anyway, back to the book. This is a pocket-sized companion, essentially the same size as a Blu-ray box. Its 120 pages are double line-spaced, making the whole thing, I estimate, around 25,000 words, which sort of limits the depth of analysis. It is also difficult to appreciate the details of the images, which could have been the one of its main selling points; in some places there are up to ten of them on any one page. The footnotes sometimes take up more page space than the main text, making one wonder if, in many cases, it might have been better to include the information within it.

Still, Osmond treads the right line between clarity and density, and there’s a wealth of really interesting material here. Arrow Books’ simultaneous publications of Osmond’s Ghost in the Shell and Tom Mes’ Unchained Melody: The Films of Meiko Kaji, to be reviewed at a later date, represent early steps into the world of the written word by one of the UK’s most hallowed film distributors. From my point of view, it’s great that they’re both based on Japanese subjects, and it is going to be interesting to see how this print line evolves.

Jasper Sharp is the author of The Historical Dictionary of Japanese Cinema.

Leave a Reply