Books: Fragrant Orchid

January 20, 2019 · 2 comments

By Jasper Sharp.

People often assume that the animated muse in Satoshi Kon’s celebration of Japan’s cinematic heritage, Millennium Actress (2001), was based on Setsuko Hara, the film star who anchored Yasujiro Ozu classics like Tokyo Story, and who retired from the screen for fifty years of self-imposed exile. There is, however, at least one other candidate contributing to Kon’s composite character. Yoshiko Yamaguchi played a controversial role in Imperial Japan’s colony of Manchuria (Manchukuo) in China, and also bowed out from the limelight at the tail end of Japanese cinema’s Golden Age, with her final film, Tokyo Holidays, released in 1958.

People often assume that the animated muse in Satoshi Kon’s celebration of Japan’s cinematic heritage, Millennium Actress (2001), was based on Setsuko Hara, the film star who anchored Yasujiro Ozu classics like Tokyo Story, and who retired from the screen for fifty years of self-imposed exile. There is, however, at least one other candidate contributing to Kon’s composite character. Yoshiko Yamaguchi played a controversial role in Imperial Japan’s colony of Manchuria (Manchukuo) in China, and also bowed out from the limelight at the tail end of Japanese cinema’s Golden Age, with her final film, Tokyo Holidays, released in 1958.

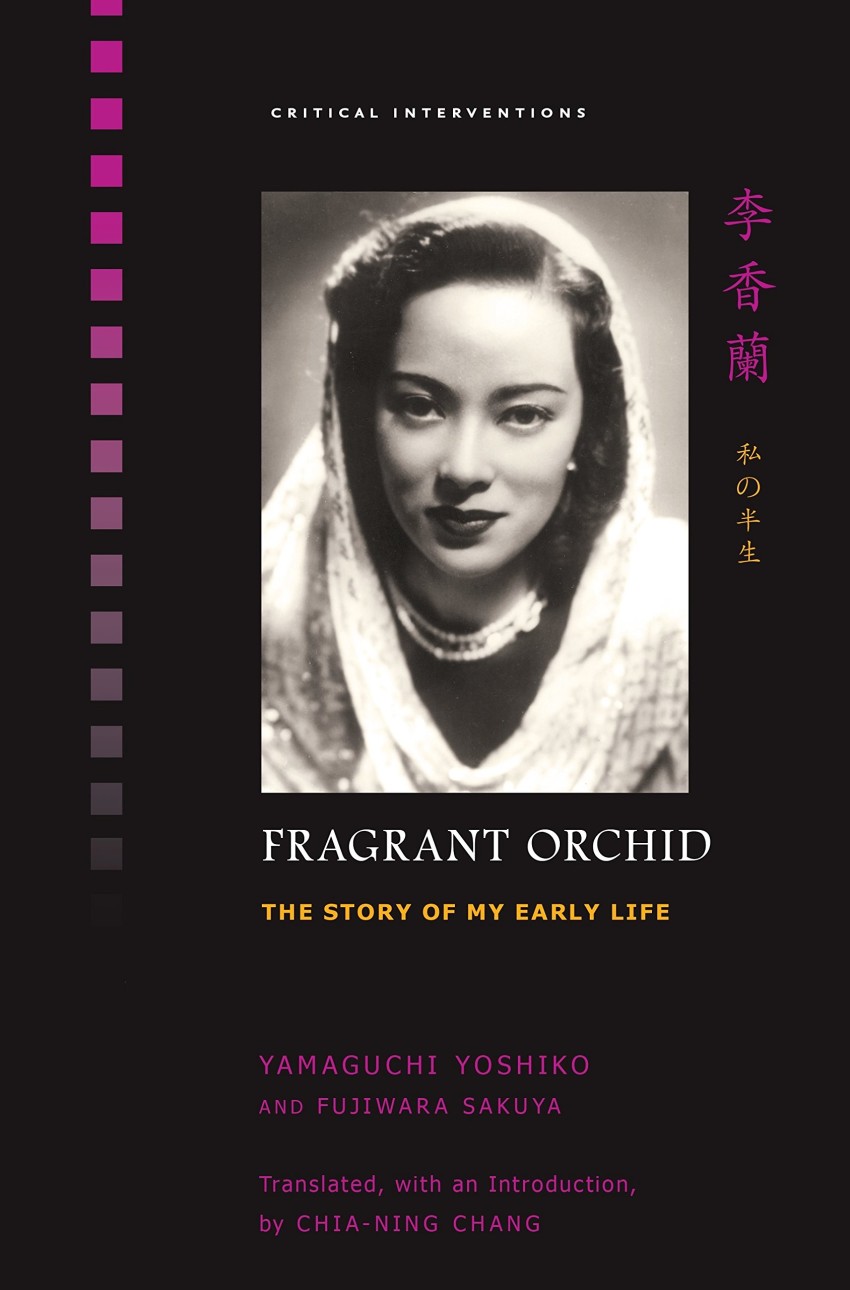

First published in Japan in 1987 as Ri Koran: Watashi no hansei (or ‘Half My Life as Li Xianglan”), her memoir Fragrant Orchid: The Story of My Early Life chronicles the intersection between national, cultural, political, domestic and personal life in Imperial Japan and its annexed territory on the Asian mainland during the war years.

Yamaguchi went under a variety of different names: Li Xianglan, Ri Koran and Shirley Yamaguchi are her best-known aliases, although she was known as Pan Shuhua and Yoshiko Otaka. But few of her movie appearances ever made it to the West. Her most noted credit under her birth name was playing against Toshiro Mifune in Akira Kurosawa’s Scandal (1950). The Toho films in which she was cast to “exotic foreigner” type, such as Hiroshi Inagaki’s Woman of Shanghai (1952), were never targeted at English-speaking audiences. Nor were her roles for Hong Kong’s Shaw Brothers in titles like Mysterious Beauty (1957) or A Night of Romantic Love (1958).

Nevertheless, her appearance in Madam White Snake (1956), an exemplary piece of Japanese chinoiserie, did inform the design of one of the characters in Japan’s first feature-length colour animation, Legend of the White Snake (1958), based on the same Chinese folk story. Meanwhile, as Shirley Yamaguchi, her demure presence in post-war American titles like Japanese War Bride (1952), House of Bamboo (1955) and Navy Wife (1956) cemented the orientalist fantasy of the passive Asian woman, packaged attractively in kimono as if embodying a national apologia for Pearl Harbor.

Nevertheless, her appearance in Madam White Snake (1956), an exemplary piece of Japanese chinoiserie, did inform the design of one of the characters in Japan’s first feature-length colour animation, Legend of the White Snake (1958), based on the same Chinese folk story. Meanwhile, as Shirley Yamaguchi, her demure presence in post-war American titles like Japanese War Bride (1952), House of Bamboo (1955) and Navy Wife (1956) cemented the orientalist fantasy of the passive Asian woman, packaged attractively in kimono as if embodying a national apologia for Pearl Harbor.

Her early career as Li Xianglan at the Japanese-run studios of the Manchuria Film Association, or Man’ei, provides ample evidence that the stereotype of the vanquished Eastern beauty was hardly the exclusive preserve of Hollywood. One might claim that never was she more central to international politics than as the poster girl for “Japanese-Manchurian Friendship”, spuriously promoted as a “Chinese” actress sympathetic to Imperial Japan. From her screen debut, age 18, in Man’ei’s Honeymoon Express (1938), through titles such as China Nights (1940) and the Taiwan-set Sayon’s Bell (1943), not to mention in performances of the songs from her movies both onscreen and off, she put in a performance so convincing it nearly cost her life.

Translator Chia-ning Chang judiciously chooses to render the name “Li Xianglan” for the title of this book as “Fragrant Orchid”, highlighting the orientalising that pushed the young actress at Japanese audiences as something Other, something foreign and exotic to Japan. But although she was born in Manchuria in 1920 and did not set foot in Japan until her late teens, Yamaguchi was wholly Japanese. Her father Fumio, a passionate Sinophile, had arrived in China in 1906 with his wife Ai, and by 1923 was earning a living teaching Mandarin to the employees of the South Manchurian Railway Company.

Attending her father’s classes from the age of four, the bilingual Yamaguchi led a carefree childhood with no real awareness of any animosity between the Japanese settlers and the local population until the climate changed dramatically one fateful day on 18th September 1931. The Mukden Incident saw the Japanese Imperial Army attack a Chinese garrison, allegedly in retaliation for dynamiting part of the track of the South Manchurian Railway. The attack was later revealed to have been staged by the Japanese themselves, as a pretext invasion. This led to the declaration of Manchukuo on 18th February 1932, a territory operating autonomously from Chinese control, effectively administered as a colony from Japan. International condemnation led to Japan’s withdrawal from the League of Nations in 1933, and the following year the last Chinese emperor of the Qing Dynasty, Puyi, was appointed Manchuria’s nominal ruler (Puyi would become the subject of Bernardo Bertolucci’s film The Last Emperor, released in the same year as Yamaguchi’s memoirs).

1932 was also the first year that the young Yamaguchi began to understand the tensions beneath the surface in her new nation. A fire at a nearby open-pit coal mine resulted in an excessively brutal reprisal by the Japanese military police against locals suspected of being members of the Chinese resistance, witnessed first-hand by the young girl from her bedroom window, with the poplar-lined streets “…changing from green to red, the red of gunfire, the color of the conflagration that night, the color of the earth at the interrogation square, and the color of blood gushing from the head coolie’s forehead.”

1932 was also the first year that the young Yamaguchi began to understand the tensions beneath the surface in her new nation. A fire at a nearby open-pit coal mine resulted in an excessively brutal reprisal by the Japanese military police against locals suspected of being members of the Chinese resistance, witnessed first-hand by the young girl from her bedroom window, with the poplar-lined streets “…changing from green to red, the red of gunfire, the color of the conflagration that night, the color of the earth at the interrogation square, and the color of blood gushing from the head coolie’s forehead.”

Yamaguchi was packed off by her parents to live with a family friend, General Li Jichun, who renamed her Li Xianglan. She would masquerade as Chinese until the end of the war, recalling that a later guardian ordered her not to smile and bow too much lest she reveal her true heritage.

Despite escalating conflicts between the Japanese colonists and Chinese insurgents, Manchuria itself comes across as a surprisingly cosmopolitan place, with the young schoolgirl’s teenage friends including Japanese and Chinese and “a young White Russian girl of Jewish extraction named Liuba Monosova Gurinets”, who introduced her to Madame Podlesov, an Italian opera singer of some renown, married to a refugee Russian aristocrat.

Madame Podlesov became singing coach of the 13-year-old who went on to perform on a special programme put together by Fengtian Radio Broadcasting entitled “New Melodies from Manchuria” in 1933. Building a common identity for the region was crucial component of Japanese and Manchurian policy, and what better medium for spreading the message than radio? The broadcasting company had been established the previous year, along with Manchukuo itself, for promoting “Japanese-Manchurian Friendship” and “Cooperation and Harmony among the Five Ethnic Races” of Han Chinese, Manchus, Mongolians, Japanese and Koreans

Other cultural enterprises soon emerged with Japanese backing, such as the Manchurian Gramophone Company, which produced and released records, and the film company Man’ei, established in August 1937. Li Xianglan was central as a performer to all these endeavours, with her films and songs circulating throughout the region. They also made it over to Japan, where she was known as Ri Koran.

There are too many details of Yamaguchi’s life to cover in a mere book review, but Fragrant Orchid triumphs in giving first-person perspectives on legendary figures from the era. Masahiko Amakasu, the notorious right-wing Imperial Army officer who ran Man’ei after spending a decade in prison for murder, puts in an appearance, as does Yoshiko Kawashima, the cross-dressing Manchu princess, party girl, and monkey-fancying opium addict. Amakasu would commit suicide at the end of the war; Kawashima was executed for treason, a fate from which Yamaguchi was spared, because she still held a Japanese passport.

And then there are the infamous incidents, recounted with an almost ironic detachment. There was the notorious scene in China Nights (1940) in which her getting slapped by her Japanese romantic interest caused huge offence to Chinese audiences. Not to mention the commotion surrounding the highly-promoted Ri Koran performance in Tokyo on 11th February 1941, the country’s only riots during the entire wartime period, triggered when thousands of spectators found themselves unable to get into the venue to catch a glimpse of the fake-Chinese songstress.

Chang does a great job in conveying Yamaguchi’s narrative. As a university publication, there are also plenty of footnotes to provide context for the historical incidents, characters and cultural moments Yamaguchi alludes to in her story that might be unfamiliar to modern non-Japanese readers.

Chang does a great job in conveying Yamaguchi’s narrative. As a university publication, there are also plenty of footnotes to provide context for the historical incidents, characters and cultural moments Yamaguchi alludes to in her story that might be unfamiliar to modern non-Japanese readers.

There is also a timeline of her life, and a rich and insightful essay about, among other things, the establishment, purpose, operating structure of Man’ei in Manchuria, unveiling some of the mysteries as to what prominent staff members like Tomu Uchida, Masahiro Makino and Japan’s first woman director Tazuko Sakane actually got up to. My only quibble is that this introductory section probably makes for better reading after one has read Yamaguchi’s own story, as it is a pretty dense read in comparison.

Yamaguchi’s own levels of culpability and collusion in a propaganda machine remain a crucial issue. In this, Chang builds upon Isolde Standish’s description of the marketing of Ri Koran to Japanese audiences as “invested with a sexualized image of what the colonies represented to the Japanese at the time of their continental expansion” and Tadao Sato’s labelling of her films as “rashamen movies”, invoking a pejorative term for Japanese women who degrade themselves as mistresses to foreigners. Perhaps most revealing is Yamaguchi’s own description of her billing for her first public radio performance. “I, Yamaguchi Yoshiko, a Japanese, was that Li Xianglan – a girl who knew nothing about the world, but still a Chinese entity concocted at the hands of the Japanese, just like Manchukuo. It pains me whenever I think about it.”

After taking the surname of the diplomat whom she married, Hiroshi Otaka, she later became a powerful political voice for women’s rights and oppressed peoples. As a host for the Fuji Television current affairs programme You at Three o’Clock between 1969 and 1974, she reported from troubled areas including Palestine, Vietnam, Saudi Arabia and Cambodia before spending a further two decades as an elected representative in the Japanese parliament. After the publication of her memoirs, she never again spoke publicly about the Manchurian years, right up until her death in 2014 at the age of 94.

Jasper Sharp is the author of the Historical Dictionary of Japanese Cinema. Fragrant Orchid is out now from the University of Hawaii Press.

John M.

December 16, 2020 7:33 am

FYI, please read: https://yoshikoyamaguchi.blogspot.com/

Jonathan Clements

December 16, 2020 7:58 am

Hello John M., I'm confused by the point you are making on your blog about Yamaguchi's nationality. The fact that the word citizen was crossed out on her marriage certificate and replaced by the word subject surely doesnt make that much difference. Japanese people were referred to explicitly as "subjects" (臣民 shinmin) in the Meiji Constitution. The fact that they were called "citizens" (国民 kokumin) under the revised constitution after 1947 was a relatively recent change in wording, and not one that seems to have endured for long in public practice; see here for example: https://www.turning-japanese.info/2013/03/do-you-become-subjects-of-emperor-when.html. Her parents were still Japanese, and she was still, presumably, the holder of a Japanese passport, which was the crucial issue in her evading trial as a war criminal in China.