Destiny: The Tale of Kamakura

January 26, 2019 · 0 comments

By Andrew Osmond.

The family fantasy Destiny: The Tale of Kamakura is at the populist end of this year’s Japan Foundation Film Programme, which tours UK and Ireland through February and March. Released in Japan over the Christmas season in 2017, Destiny is a little like Harry Potter, and a little like Ghibli. It’s also like watching several episodes of a cosy TV drama about characters’ daily lives, though several of those characters happen to be ghosts, reincarnated spirits or non-human beings.

The family fantasy Destiny: The Tale of Kamakura is at the populist end of this year’s Japan Foundation Film Programme, which tours UK and Ireland through February and March. Released in Japan over the Christmas season in 2017, Destiny is a little like Harry Potter, and a little like Ghibli. It’s also like watching several episodes of a cosy TV drama about characters’ daily lives, though several of those characters happen to be ghosts, reincarnated spirits or non-human beings.

Kamakura is one of the most famous locations in Japan. It had a pivotal role in Japan’s history, but the film hardly even mentions that. Rather it plays up the area’s charms today as a tourist and beauty spot, easily accessible from Tokyo. One of the most fondly regarded features of the area is a lovely train-tram called the Enoden, which trundles beside the sea or winds between residential houses that you could reach out and touch. In Destiny, both the real Enoden railway and a secret magic version of it play important roles.

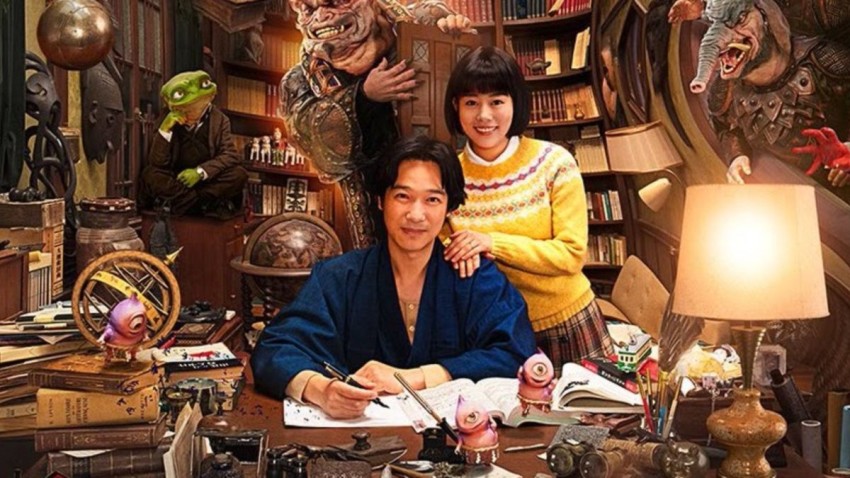

To this idyll comes young, cute-as-a-button Akiko (Mitsuki Takahata), who’s just married eccentric local author and folklorist Isshiki (Masato Sakai). Though Akiko loves him to bits, she finds living as Isshiki’s wife has challenges and surprises, from his boyish hobbies (he collects model trains as avidly as Mirai’s toddler) and his insistence that Kamakura is home to all kind of magic folk. It’s soon obvious that Isshiki is right, though Akiko takes a while to cotton on… but even Isshiki is startled about what Akiko can take in her stride.

As touched on above, much of this leisurely film is paced like a “daily life” drama, with little story strands replacing each other; for example, Isshiki solving a murder mystery that even Watson would find elementary, and the story of a friend who’s near death but still wants to oversee his family, even if he’s saddled with a frog’s head. But a bigger challenge causes the newlyweds anguish, and leads into the most spectacular part of the film by far. The climax takes our couple deep into the realms of fantasy, with visual echoes of neverlands in both anime and Hollywood blockbusters.

Incidentally, keep an eye on a rather friendly (if scatty) “death god” character, lightly played by Sakura Ando. She had a far more emotionally heavyweight role recently, as the motherly Nobuya in Hirokazu Kore-eda’s acclaimed Shoplifters.

Destiny is directed by Takashi Yamazaki, who has a deep affinity with CG, anime and manga. Readers of this blog may know him for his live-action adaptations of the horror manga saga Parasyte (a two-part film) and of the anime Space Battleship Yamato. In Japan, he’s probably better-known for his kamikaze drama The Eternal Zero, which was furiously condemned by some parties – including Hayao Miyazaki, director of another contentious film about warplanes – but was praised by Japanese PM Shinzo Abe.

Destiny is directed by Takashi Yamazaki, who has a deep affinity with CG, anime and manga. Readers of this blog may know him for his live-action adaptations of the horror manga saga Parasyte (a two-part film) and of the anime Space Battleship Yamato. In Japan, he’s probably better-known for his kamikaze drama The Eternal Zero, which was furiously condemned by some parties – including Hayao Miyazaki, director of another contentious film about warplanes – but was praised by Japanese PM Shinzo Abe.

Yamazaki has also made fully-animated CG films, including a version of the famous Doraemon cartoon that was another box-office smash. His backlist also includes Ballad, a live-action tale of a time-travelling boy; weirdly, it was a remake of an anime film directed by Keiichi Hara (Miss Hokusai) which originally featured the very cartoony Crayon Shin-chan. But Yamazaki’s most heartfelt opus may be his live-action film trilogy Always: Sunset on Third Street. Released in cinemas between 2005 to 2014, it related the experiences of a set of Tokyo characters in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

Although Always wasn’t a “fantasy” work, it still let Yamazaki showcase the work of his animation and effects studio, Shirogumi, to recreate the Tokyo of half a century ago. There’s a direct link between Always and the fantastical Destiny – they’re both based on strips by the artist Ryohei Saigan, whose work was not translated into English till last October. That was when Futabasha started publishing a translation of Destiny’s source strip; even in its “translated” edition, it’s called Kamakura Monogatari. Saigan has a highly idiosyncratic, cartoony art style, which may explain the delay in releasing his work in English.

For viewers who don’t have that reference point, Destiny may rather remind them of other supernatural manga/anime, such as The Ancient Magus’ Bride (which has comparable goings-on to Destiny, in mostly British settings) or Gegege no Kitaro. Given that Saigan’s Kamakura manga reportedly runs around thirty volumes, perhaps Yamazaki’s film will encourage an anime studio to have its own crack at the adventures of Akiko and Isshiki.

Andrew Osmond is the author of 100 Animated Feature Films. Destiny: The Tale of Kamakura is screening as part of the Japan Foundation Film Programme in February-March 2019.

Leave a Reply