Impressions of Perfect Blue

March 19, 2019 · 0 comments

By Andrew Osmond.

Satoshi Kon’s Perfect Blue, which Anime Limited is releasing in a new “Ultimate” edition, is a slasher film, a psycho-thriller, and a riddle which may have no answer. In my book Satoshi Kon: The Illusionist, I wrote, “No matter which Kon film, you start with” – which for many fans would be Perfect Blue, Kon’s director debut in 1997 – “each takes you in and around what feels like the director’s private funhouse, a warped maze that look different depending on which entrance you choose.”

(Warning: the second half of this article has spoilers for the end of the film.)

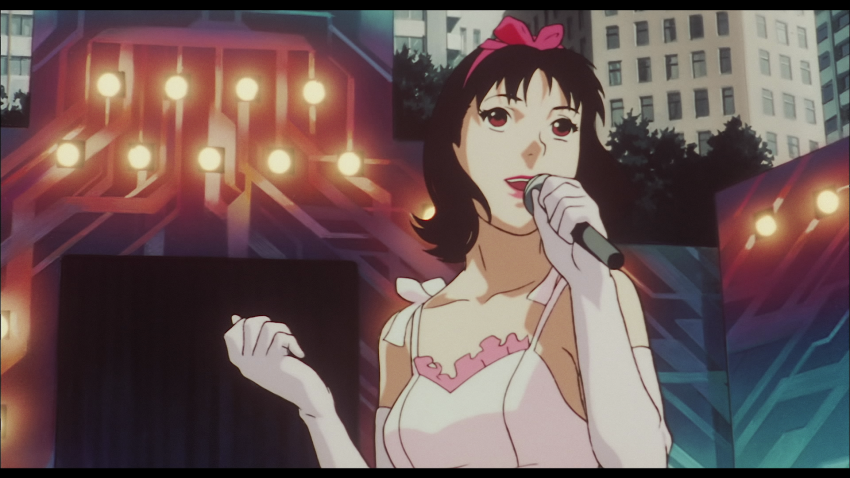

Even individually, Kon’s films have many entrances, Perfect Blue most of all. It’s about a young idol singer, Mima, trying to change careers; about her breakdown from the inside; about a celebrity’s embattled sense of self; and about red-meat violence, sexual exploitation, and the clinical deconstruction of a rape scene.

You can see Perfect Blue as horror or post-horror, as reflecting on deep Japanese values or on transient J-pop. You can link Mima to the disintegrating heroines of Polanski’s Repulsion and Hitchcock’s Vertigo, or see her torments as a bloody fairy-tale like Argento’s Suspiria, or a fugue like Lynch’s Mulholland Drive. There’s also the “Manga” context. Perfect Blue came to Britain and America when anime was widely perceived as an Extreme Asia sub-genre, with the frisson of doing things “cartoons” could never do.

Anime fans hadn’t heard of Kon, but they knew Perfect Blue’s studio, Madhouse, for X-rated fare like Wicked City and Ninja Scroll. Unlike them, Perfect Blue never felt the BBFC’s scissors, though it was rated 18 for “strong violence, nudity and language.” (The Kon anime that would be censored in Britain was Paranoia Agent, which lost a macabre 80-second scene where a child “plays” at hanging herself. “Swing! Swing!”)

Anime fans hadn’t heard of Kon, but they knew Perfect Blue’s studio, Madhouse, for X-rated fare like Wicked City and Ninja Scroll. Unlike them, Perfect Blue never felt the BBFC’s scissors, though it was rated 18 for “strong violence, nudity and language.” (The Kon anime that would be censored in Britain was Paranoia Agent, which lost a macabre 80-second scene where a child “plays” at hanging herself. “Swing! Swing!”)

Certainly Perfect Blue is a horror film and a great one. In America, one of the biggest Perfect Blue articles was an in-depth four-page piece in the horror bible Fangoria (August 1999). Naturally, it played up the comparisons to horror-film makers like Argento… though it also acknowledged that Kon hadn’t seen any Argento before he made Perfect Blue. Still, the director acknowledged the power of genre. “If Perfect Blue could attract people who loved thrillers like Seven, I’ll be a very happy man,” he said in the Fangoria article.

Gary Dauphin in New York’s Village Voice drew attention to Perfect Blue’s status as a animated horror film, suggesting this allowed for a particular kind of perverse play. “The film,” Dauphin said, “is tawdrily insightful in the way it uses the hot lights of the entertainment industry to illuminate anime’s peculiar duality as the mirror of both wholesome and not-so-wholesome fantasy, and this with nary a tentacled demon-dick in sight.” This phallic parting shot refers to Legend of the Overfiend, still overshadowing anime’s reputation in Britain and America in 1999. Two years later, Madonna’s “Drowned World” concert tour spliced images from Perfect Blue and Overfiend IV.

In Britain, Jonathan Romney also homed in on the mirroring of wholesome and salacious fantasies in Sight and Sound. “It’s no accident,” Romney said, “that Mima’s television character [in Double Bind] is dressed as a soft-porn version of the Cham look [Mima’s former idol group] in her rape scene.” For Romney, though, the main benefit of making Perfect Blue in animation was in the film’s endless, infuriating repetitions and replays, “a brilliant use of the hallucinatory repetitiveness of commercial animation.”

Romney also pointed up the contrast between the film’s real world setting and its “pop and manga” images. There’s an early moment, almost a jump scare in a film without jump scares, when Kon hits us with a huge-eyed “anime” girl that’s revealed to be a poster. For Romney, the poster image looks “much more three-dimensional than the film’s real world… The everyday becomes a colour-drained place of exile from the pop universe.”

The first edition of the Anime Encyclopedia in 2001 disagreed with this writing-off of reality, praising Perfect Blue’s “loving” rendition of contemporary Tokyo. While Romney claimed that Kon “goes for a flat, flimsy look… dropping in jolts of visual complexity,” Tony Rayns was more generous in London’s Time Out. “Despite the usual cost-saving short-cuts,” Rayns said, “the animation is rather fine; striking compositions, beautiful background, good pacing.” Over in the specialist Manga Max, Chrys Mordin compared the backgrounds to the Patlabor anime – Kon had worked on backgrounds and layout for 1993’s film Patlabor 2. “The hyperrealistic backgrounds and the more human feeling of the character designs contribute to the sense of reality and sweep the viewer along when that reality begins to dissolve.”

Some reviewers considered whether Perfect Blue transcended its genre. Despite praising the film, Rayns thought not. “Perfect Blue follows Polanski’s Repulsion into some fairly grown-up areas…. If the material never quite transcends the genre, there’s no doubt that doing it as an animated feature gives it an edge.”

Kim Newman, famous for his horror criticism, chose to begin his Empire magazine review from another genre perspective. “The buzz that sprung around Japanese animation when Akira and a very few other amazing movies showed up in the West has diminished somewhat,” Newman wrote, “with video sell-through shelves groaning under the weight of repetitive, noisy Anime (sic) about shrill gun-toting Lolitas, demon rapists and giant robot warriors. This striking picture is about as far as it’s possible to get from those conventions.”

Although Newman brought up De Palma and Argento, he also labeled Perfect Blue a neat woman-in-peril thriller; he mentioned the gore and violence, but also that the film is “scary, funny, poignant and thoughtful.” Such human qualities were also stressed by Irvin Kershner, blockbuster director of Empire Strike Back, who was quoted on a press release for the film. “I found Perfect Blue to be an exceptional film of this genre… I was caught up in the way the industry manipulated the lonely innocent young pop star. I cared for (Mima) and was quite moved by the way she fell from grace by trying to please the men who used her to make money.”

Similarly, the Anime Encyclopedia acknowledged comparisons to Vertigo and Suspiria, but found Perfect Blue “has ultimately a less bleak and more humane agenda.” I took a similar line in my Perfect Blue chapter in my Illusionist book, where I highlighted Mima, granting her many contradictions and issues, but arguing that by the end, Mima is what she declares she is, “a real person at the heart of Perfect Blue’s box of tricks.”

I wrote The Illusionist in 2009, three years after Kon had released Paprika, when everyone in fandom still thought there were many more Kon films to come. Even by that time, there was a new way to see Perfect Blue; namely as a Satoshi Kon anime, tied by themes and sensibility to the three films and one TV series he made later. Back in 1997, one might have reasonably speculated that Kon would stay in a horror genre; he didn’t. Of his later work, only Paranoia Agent can be labeled as horror, and it’s really more of a dark satire. Episode three, “Double Lips” even retells Perfect Blue as a delicious camp black comedy.

The reversals in Kon’s other anime – Millennium Actress, Tokyo Godfathers and Paprika – are more radical. Contra Perfect Blue, these films are upbeat, comedic and romantic. Otaku men are no longer obsessed monsters like Me-Mania, but sweet supporters of Kon’s heroines. Multiple realities aren’t collapsing mazes of madness, but joyous Gilliamesque playgrounds. Even the taunting phantom Mima is reconfigured as Paprika in that film’s wonderful opening titles, riding cartoon rockets.

Looking back from these works, some things in Perfect Blue do add up more; the end, for example. When Perfect Blue first came out, it seemed so weird that it had a happy ending. Personally, I think other things are more radical, like Perfect Blue being a slasher film where all the women survive, but that ending seems to bother people. It’s partly genre baggage. By the late 1990s, it was almost mandatory in Hollywood for horror films to have “shock” endings that, of course, soon were anything but shocks. For a film with warped, transforming realities, it was especially mandatory that the last scene would have some trapdoor reveal.

I’ve seen online theories that Perfect Blue has a sinister end after all; that for example, the red colour of Mima’s car in the last scene signifies, via the film’s chromatic coding, that she’s actually possessed by the phantom-Mima. I find that as persuasive as The Shining’s faked moon landing and the Totoro Death God. Meanwhile, Christopher Bolton suggests that even if such theories don’t hold up, they should. In his book Interpreting Anime, he recommends recovering “an interesting sense of openness” by viewing Perfect Blue’s end as a “simulation or delusion.” But that’s not interpreting, that’s fanfic.

Indeed Kon did all that in the film itself. There’s a fake end in the later scenes when Mima is revealed be the fictional persona of a traumatised rape victim… at least she is until Kon rewinds the scene, Haneke-style, and switches the dialogue around. Perfect Blue’s happy end may not fit with “genre” horror or with how a David Lynch fan thinks it should have ended, but it does fit well with Kon’s subsequent, upbeat work. The divide between Kon’s film and some of its critics recalls the divide between Kubrick’s and King’s Shinings; the chilly mystery of the film’s photograph, versus the source book’s insistence that evil can be beaten.

I’d also argue there’s still an “open” mystery regarding what’s exactly happening in Perfect Blue. Is all the weirdness in the characters’ unglued minds, or are they wandering some surrealist’s spiral, like the dream-in-a-dream wrapping the classic British film Dead of Night? Kon ruled out any supernatural reading of Perfect Blue when I interviewed him, but the viewer is free to disregard that and tie in Perfect Blue with the paranormal activity of Paprika and Paraonia Agent, which both reference Perfect Blue extensively. Unlike fanfic, it has textual support.

The moment that bothers me most in Perfect Blue today is actually something else. During the film’s climax, just before the final fight, there’s a moment where the terrified Mima is chased into an alley by Rumi and finds herself facing her reflection in a window. The moment is held for a couple of seconds, and the music softly drops, before Rumi leers up in the image, reflected as Rumi. There’s a suggestion of realization on Mima’s (reflected) face before Rumi lunges at her.

Disconcertingly, although I watched the film many times through the years, the moment never registered with me until I rewatched it only a couple of years ago. I’d always been overwhelmed by the landslide of experiences just before; Mima’s raw terror, the pursuit, the screams, and the twinned monsters in red idol dresses, lithe and large. Yet the mirror scene may be the film’s defining existential moment. And appropriately, it foreshadows a moment in a later anime that’s not a horror film, though it is big on reflected faces. I’m thinking of the bit at the end of Your Name where two characters see each other through the windows of passing trains, and it’s like they’re each looking in a mirror.

Andrew Osmond is the author of 100 Animated Feature Films. Perfect Blue is released in an Ultimate Edition by Anime Limited.

Leave a Reply