From Gurren Lagann to Promare

May 13, 2020 · 0 comments

By Andrew Osmond.

Gurren Lagann, available to watch on Blu-ray and All4, and Promare, also available on home video formats, both share a love of Big Dumb Anime Action. Mecha-riding heroes punch through frames at lightning speed while the world swivels and curly-wurlys to keep up. They also share a history and director: Hiroyuki Imaishi. This blog interviewed Imaishi and his colleagues last year, where he spoke of growing up on action animation; he was born in 1971, when the genre itself took flight. “I always liked action, robot animation; they’re not slow or atmospheric,” he said. “Or kids fighting; I liked that sort of thing since I was a child.”

Gurren Lagann, available to watch on Blu-ray and All4, and Promare, also available on home video formats, both share a love of Big Dumb Anime Action. Mecha-riding heroes punch through frames at lightning speed while the world swivels and curly-wurlys to keep up. They also share a history and director: Hiroyuki Imaishi. This blog interviewed Imaishi and his colleagues last year, where he spoke of growing up on action animation; he was born in 1971, when the genre itself took flight. “I always liked action, robot animation; they’re not slow or atmospheric,” he said. “Or kids fighting; I liked that sort of thing since I was a child.”

The anime of his childhood, Imaishi claimed, inspired his sense of humour, often with sex and toilet jokes. “That was my rebellious feeling towards everything. When I started out, all this naughty stuff was torn down, anime was quite gentrified. But I think the anime I used to watch when I was a child were more sexy. Actually, I didn’t make anything sex-related when I was making my own indie things; I started doing it once I was in [the industry] because everything was torn down and I just wanted to do something different.”

Notably, though, Promare tones down that side of Imaishi’s work greatly, though restraint is the last thing you think of when you’re watching the film. Perhaps that’s the deepest measure of how Imaishi has evolved – making a film that’s suitable for all ages, and keeping the madcap sensibility for which he’s beloved.

Imaishi started in anime in the mid-1990s. One of his first credits was at the Gainax studio on the original TV Evangelion, doing in-between animation. Soon he began making his own name in the industry for funny, fizzy, aggressively crazy animation work. A milestone for Imaishi, though not an “Imaishi” anime, was 2000’s FLCL (aka “Fooly Cooly”). Imaishi made multiple contributions to the series, both in storyboarding and animation. He didn’t create FLCL’s manic style, anime’s equivalent of a motormouth Robin Williams stand-up, but he revelled in it.

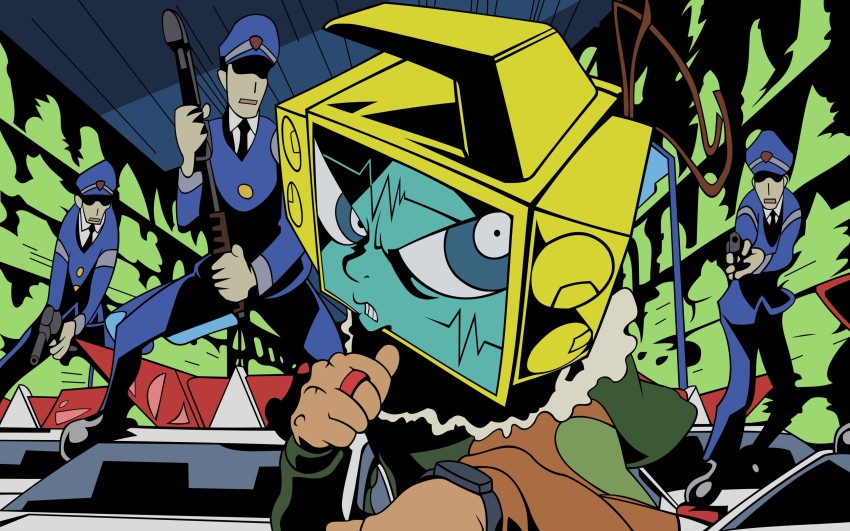

Four years after FLCL, Imaishi made his director debut with Dead Leaves. It was a 52-minute film, made not by Gainax but Production I.G (which had collaborated on FLCL). It was the world’s introduction, not just to director Imaishi, but to filthy director Imaishi, incontinent director Imaishi. It starts with the amnesiac, delinquent heroes – a TV-headed man and a rainbow-eyed woman – joyriding through a city and blowing away armies of police. Then they’re sent to the moon and the rest of the film is a prison break punctuated by punch-ups, pooping, sex, more violence and monstrous developments arising from the sex.

Four years after FLCL, Imaishi made his director debut with Dead Leaves. It was a 52-minute film, made not by Gainax but Production I.G (which had collaborated on FLCL). It was the world’s introduction, not just to director Imaishi, but to filthy director Imaishi, incontinent director Imaishi. It starts with the amnesiac, delinquent heroes – a TV-headed man and a rainbow-eyed woman – joyriding through a city and blowing away armies of police. Then they’re sent to the moon and the rest of the film is a prison break punctuated by punch-ups, pooping, sex, more violence and monstrous developments arising from the sex.

Dead Leaves had very mixed reviews; the Anime Encyclopedia was especially damning. But if Dead Leaves’ bombast was received as a vulgar fart, Gurren Lagann was a volcano.

Imaishi didn’t “originate” Gurren Lagann. It emerged out of development at Studio Gainax – yes, it’s worth stressing Gurren Lagann was by Gainax, though the series is now closely identified with Trigger. After the first plans (by different staff) fell apart, the studio approached a writer called Kazuki Nakashima. His respectable job was as a playwright, but he moonlighted in anime as well. In particular, Nakashima had given his services to Gainax on a 2004 video miniseries called Re: Cutie Honey, starring a saucy 1970s superheroine created by Go Nagai.

Also involved on that series was Imaishi, who instantly found Nakashima’s writing appealing. When Imaishi heard Nakashima was on board Gainax’s new mecha show, he immediately offered to direct. Later Imaishi would hail Nakashima as a writer capable of applying adult skills to the illogical humour that a primary schooler would have; creating something ridiculous, but intelligently ridiculous.

Gurren Lagann came armed with wind-blown capes, muscular pouty poses and hammered-home nob gags. In Nakashima’s story, two young men, Kamina and Simon, drill their way out of their underground home and find a planet teeming with enemies driving robot monsters. Luckily our heroes pick up some mecha themselves, plus a curvy lady called Yoko and a caravan of allies, rising up the levels to bigger and bigger baddies. Kamina is a vainglorious jock, Simon a shrinking wimp, bolted together in the “manly combining” of their robot steeds. But will Yoko break them up, Beatles-style? Actually no – the show had a bigger shock in store.

Gurren Lagann came armed with wind-blown capes, muscular pouty poses and hammered-home nob gags. In Nakashima’s story, two young men, Kamina and Simon, drill their way out of their underground home and find a planet teeming with enemies driving robot monsters. Luckily our heroes pick up some mecha themselves, plus a curvy lady called Yoko and a caravan of allies, rising up the levels to bigger and bigger baddies. Kamina is a vainglorious jock, Simon a shrinking wimp, bolted together in the “manly combining” of their robot steeds. But will Yoko break them up, Beatles-style? Actually no – the show had a bigger shock in store.

Interviewed by the Forbes website, Imaishi made clear he saw Gurren Lagann as part of a venerable genere’s life-cycle. In anime of the 1970s and 1980s, heroes piloted mecha willingly and wholeheartedly. Evangelion tried to stop that; it revolves around the hero’s hatred of the mecha that he’s ordered to pilot. Imaishi, though, had had enough of tortured refusals. No-one needed order him into a robot. “From my standpoint, if someone asked me to pilot a mecha, I would, even if they said I wasn’t allowed to.”

Although Imaishi had grown up with Gundam, Gurren Lagann often recalls the crazier, more fantastical robot shows which preceded it; what mecha fans call the “super robot” anime, shaped by creators like Go Nagai. Imaishi suggests this reflects the influence of Nakashima; the writer was a fan of 1970s anime like Mazinger Z and Getter Robo, both Nagai creations. But Gurren Lagann also reflected Imaishi’s own cartoon humour. Just in the opening minutes, for example, Kamina and Simon ride a snorting stampede of “pig-moles” which piles up impossibly into a huge porcine tower, lifting our heroes aloft. It’s a fair measure of just how loose Gurren Lagann’s reality is going to be.

Like the old “super robot” series, Gurren Lagann was broadcast on Japanese TV when children might have been watching, before 9pm. This was unusual in 2007, when most TV anime were already relegated to late at night. You might think Gainax had learned lessons when Evangelion, also shown in a mainstream time-slot, got into trouble with TV networks for having a (tasteful) bed scene between adults. Hardly – one of Gurren Lagann’s first episodes was a lewd bathhouse farce, which had to be censored for broadcast at the last minute. (Don’t worry, that doesn’t apply to the version on All4.)

Like the old “super robot” series, Gurren Lagann was broadcast on Japanese TV when children might have been watching, before 9pm. This was unusual in 2007, when most TV anime were already relegated to late at night. You might think Gainax had learned lessons when Evangelion, also shown in a mainstream time-slot, got into trouble with TV networks for having a (tasteful) bed scene between adults. Hardly – one of Gurren Lagann’s first episodes was a lewd bathhouse farce, which had to be censored for broadcast at the last minute. (Don’t worry, that doesn’t apply to the version on All4.)

But unlike Dead Leaves, Gurren Lagann wasn’t just for laughs. It had an epic story, the kind of story that gets bigger and bigger and bigger, and characters that audiences rooted for and sometimes cried for. Imaishi and Nakashima weren’t scared of upsetting fans, but the fans didn’t resent them for it. Just check how high Gurren Lagann is ranked on the main anime fan websites, thirteen years after its TV debut.

Imaishi’s next Gainax series was without Nakashima. The idea came from another of Imaishi’s collaborators, Hiromi Wakabayashi. Panty & Stocking with Garterbelt was more high-speed nonsense a la Dead Leaves, about a pair of fallen girl-angels who look like fallen Powerpuff Girls, zooming around on random missions. Like Dead Leaves, Panty & Stocking was most fun to watch in its chases, with characters shrieking and zagging across the frame.

The next Imaishi anime was the first made at a new studio. In October 2011, Imaishi co-founded Studio Trigger. Wakabayashi told me that Gainax had been liberal in terms of creative freedom. “Only Gainax would have done Panty & Stocking with Garterbelt, any other studio wouldn’t have done it. But the bosses at Gainax, the generation who had made The Wings of Honneamise, what they wanted to do was different from what we wanted to do. So rather than being safe, making what would make everybody happy, we thought we might want to do what we wanted, and be responsible for what we make. It was like a natural progression.”

Two years after its founding, Trigger released a new TV epic, with Imaishi once again directing and Nakashima as the main writer. Kill la Kill had all the lunacy of Gurren Lagann; it starts with a teacher, who looks roughly the size of a dinosaur, crashing into a classroom. It also had much of the crudity of Panty & Stocking, with its heroine Ryoko bound up in an eye-watering vampiric sailor super-suit to battle authority. This blog once interviewed Takeshi Honda, a master Japanese animator who drew Ryoko’s outrageous “transformation” scene, which looks like pole-dancing crossed with BDSM. Honda said it embarrassed even him.

But Kill la Kill also had an energetic evolving story, fortified by strong twists, and with amusing satirical comments about the dangers of global clothes brands. (By Nakashima’s admission, this strand of the series was inspired by The Garments of Caean, a 1976 British novel by Barrington J. Bayley.) Some fans discerned deeper themes about society and identity in the show, even as Nakashima says his main inspirations included vintage Japanese exploitation flicks, the so-called “Pinky Violence” series released by the Toei studio. For the average reader, Kill la Kill is simply a Shonen Jump-style battle show with scantier costumes and more stupendous visuals.

Following Kill la Kill, Imaishi had several director credits on smaller, gag-filled toons for Trigger. One of them, “Oval x Over” can be found on Anime Limited’s Pigtails collection. Meanwhile Trigger has produced an impressive range of other anime, some helped along by Imaishi, but mainly the work of younger directors. When I asked if Trigger had an underlying “style,” Wakabayashi played down the idea. “We don’t really think of genre or style as such. We just want to do what the directors or staffers want to make, what they find funny or interesting or exciting. As a result, there might be ‘our’ style, but it’s not something we’re actually aware of.”

Yoh Yoshinori, who helped design mecha on Gurren Lagann, created the delightful Little Witch Academia. In his words, it was an experiment to “make something as interesting as Gurren Lagann and Kill la Kill without the extreme elements.” The result was family-friendly and hilarious; two original films were followed by a 25-part TV series, which can be found on Netflix. Imaishi himself storyboarded the eighth series episode, set in a zany dream world. Yoshinori is now directing the (at time of writing) upcoming Trigger series BNA: Brand New Animal (trailer), which will apparently come to Netflix too.

Trigger’s other work includes Kiznaiver, available from Anime Limited. Written by Mari Okada, it’s a winning drama about teenagers bound together by their pain; you can read more about it here. Meanwhile, other teens developed superpowers in Trigger’s series When Supernatural Battles Become Commonplace. Trigger’s first mecha epic was the contentious DARLING in the FRANXX, directed by Gurren Lagann’s character designer Atsushi Nishigori. Trigger made it in collaboration with A-1 Pictures. More recently, SSSS.Gridman was an especially “meta” mecha series, set in what’s ostensibly the present day (but is it?), which pays fulsome tribute to Japan’s live-action tokusatsu effects series.

When Trigger finally released a major new anime directed by Imaishi, I reviewed it in Sight & Sound magazine. “Promare is full of crashing, exhausting battles between grinning, roaring men piloting robots the size of buildings. It’s a vehement statement of fannish self-celebration, like the massing armies of costumed heroes in the finale of Avengers: Endgame… The artists’ love of the material can’t be faked. The visuals emphasise basic shapes – squares, triangles, the smoothly curving tracks of an elevator which bring dynamism to the stock scene where the villain explains his plot. Together with a vibrantly stylised red-and-blue colour scheme, Promare’s aesthetic recalls a far artier animation, Hungary’s 1981 myth-fantasy feature Son of the White Mare.”

By Imaishi’s own account, he and Nakashima had been wrestling with Promare’s story pretty much ever since Kill la Kill. They were “blocked” for years over what story to tell. Then they went out for a hamburger meal and resolved to serve up a “standard delicious” work, in line with their usual style. Promare’s producer Hiromi Wakabayashi calls the new film “a compilation of all of Imaishi’s works up until now.” That explains a great deal; and with the sex and toilet jokes left out, Promare could bring Imaishi to the widest audience yet.

Andrew Osmond is the author of 100 Animated Feature Films. Promare is released in the UK by Anime Limited.

All4, Andrew Osmond, anime, Dead Leaves, gurren lagann, Hiroyuki Imaishi, Japan, Promare, Trigger

Leave a Reply