Nobuhiko Obayashi & Hanagatami

July 6, 2020 · 0 comments

By Jasper Sharp.

Hanagatami (2017) has to be among the most important Japanese films of the last 20 years. This sweeping, emotive and flamboyant tale of love and friendship among a group of six college-age teenagers whose lives are about to be changed irrevocably by WW2 is an undisputable masterpiece for Nobuhiko Obayashi, a filmmaker with a brilliant career of some six decades already behind him. It was widely acclaimed in the year of its release, and met with international festival attention at Rotterdam, Fantasia and New York’s Japan Cuts. So why does it seem to have been completely overlooked in the UK, and is only now getting its belated debut on Blu-ray thanks to Third Window Films?

Hanagatami (2017) has to be among the most important Japanese films of the last 20 years. This sweeping, emotive and flamboyant tale of love and friendship among a group of six college-age teenagers whose lives are about to be changed irrevocably by WW2 is an undisputable masterpiece for Nobuhiko Obayashi, a filmmaker with a brilliant career of some six decades already behind him. It was widely acclaimed in the year of its release, and met with international festival attention at Rotterdam, Fantasia and New York’s Japan Cuts. So why does it seem to have been completely overlooked in the UK, and is only now getting its belated debut on Blu-ray thanks to Third Window Films?

Part of the reason may be its length. A 168-minute duration signals a daunting slog for some, although remarkably Hanagatami never feels overstretched. Another factor might be that while Obayashi is not entirely an unknown quantity due to modern viewers’ relatively recent discovery of his goofy ghost-movie House (1977), the bulk of the director’s output has received little attention outside of Japan. Obayashi is, indeed, a tricky figure to get a handle on, having spent a lifetime negotiating independent artistic film, the advertising world, animation, auteurism, and popular commercial entertainment.

In 1964, he was a part of the delegation of Japanese avant-garde filmmakers, which also included Takakiko Iimura and (somewhat ironically) Donald Richie, who received a group prize at Belgium’s legendary Knokke-Le-Zoute Experimental Film Festival. Obayashi’s own 8mm and 16mm endeavours come across less as serious artistic statements, than as playful explorations of the seemingly endless absurdist potential of film media. Tabeta hito (1963), for example, presents a grotesque vision of a restaurant waitress daydreaming of her evisceration in the kitchen by the chef, who, after removing bloody wads of spaghetti and strings of sausages from her stomach to be served up to the assorted diners, proceeds to cover her face with pie dough and bake her.

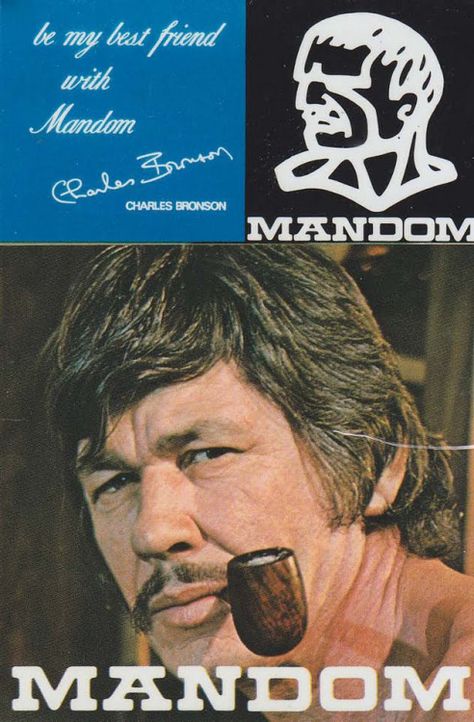

Such inventive shorts saw him ideally suited to the more lucrative field of advertising, creating the now-legendary commercials featuring Charles Bronson hawking an aftershave name Mandom. They are obvious signposts to the no-holds-barred dream logic manifested by his feature debut with House, in which a series of high-school-girl protagonists are subjected to a series of ludicrous demises involving pianos, watermelons and swimming pools within the cartoonishly-rendered haunted mansion of the title. One can see parallels with the British contemporary Alan Parker. Both directors’ then unconventional routes into feature filmmaking via television advertising is evident in the oddball eccentricity of their debuts. House came out just a year behind Bugsy Malone, and in a further piece of serendipity, both films’ scripts were heavily shaped by the input of the directors’ own children: Obayashi’s 12-year-old daughter Chigumi has an onscreen ‘Story’ credit for the former, while Parker’s young son made the bold suggestion of casting kids in his film.

Such inventive shorts saw him ideally suited to the more lucrative field of advertising, creating the now-legendary commercials featuring Charles Bronson hawking an aftershave name Mandom. They are obvious signposts to the no-holds-barred dream logic manifested by his feature debut with House, in which a series of high-school-girl protagonists are subjected to a series of ludicrous demises involving pianos, watermelons and swimming pools within the cartoonishly-rendered haunted mansion of the title. One can see parallels with the British contemporary Alan Parker. Both directors’ then unconventional routes into feature filmmaking via television advertising is evident in the oddball eccentricity of their debuts. House came out just a year behind Bugsy Malone, and in a further piece of serendipity, both films’ scripts were heavily shaped by the input of the directors’ own children: Obayashi’s 12-year-old daughter Chigumi has an onscreen ‘Story’ credit for the former, while Parker’s young son made the bold suggestion of casting kids in his film.

Obayashi’s subsequent run of work was very much in the youth-oriented commercial vein and defined the viewing habits of Japanese viewers growing up in the 1980s. Notable hits include the body-swap comedy Exchange Students (aka I Are You, You Am Me, 1982) and The Girl Who Leapt Through Time (1983), the original live-action version of the 1967 sci-fi novel by Yasutaka Tsutsui better known nowadays due to Mamoru Hosoda’s animated adaptation from 2006. The Drifting Classroom (1987) was another live-action adaptation of a classic manga (this time by Kazuo Umezu), in which the titular classroom, with its students still inside, is whisked away by a tornado, Wizard of Oz style, and plunked right in the heart of a barren desert in a distant time and place. The decision to change the setting to an international school in Kobe, with the Japanese actors performing in stilted English alongside their American counterparts, including Troy Donahue as the teacher, was a clear attempt to pitch this youth-oriented fantasy to more international markets, but alas, it ultimately never crossed the divide.

Manga and anime fans might also be aware of Obayashi’s work directing Kenya Boy (1984), a feature-length animated adaptation of the African adventure manga series by Soji Yamakawa that was highly-popular in the 1950s but has now, for fairly obvious reasons, slipped into obscurity. Obayashi’s anime nevertheless boasts an eccentricity, inventiveness and technical merit that might make it worth looking past its air of cultural tone deafness for curious modern-day viewers.

As might be discerned from such descriptions, Obayashi’s oeuvre is not really the stuff of international arthouse retrospectives, and even such later titles as Sada (1998), a considerably less sexually explicit version of the same real-life tale behind Nagisa Oshima’s scandalous In the Realm of the Senses (1977), or the murder-mystery of The Reason (2004), belong within a commercial mainstream of Japanese studio cinema that resists the attention of festival programmers. That said, I should certainly give a shout out to Mark Schilling’s focus on the director at the 2016 Udine Far East Film Festival, where the director received the Golden Mulberry Lifetime Achievement Award, while New York’s Japan Cuts festival (online, for obvious reasons this year) is celebrating Obayashi’s legacy.

As might be discerned from such descriptions, Obayashi’s oeuvre is not really the stuff of international arthouse retrospectives, and even such later titles as Sada (1998), a considerably less sexually explicit version of the same real-life tale behind Nagisa Oshima’s scandalous In the Realm of the Senses (1977), or the murder-mystery of The Reason (2004), belong within a commercial mainstream of Japanese studio cinema that resists the attention of festival programmers. That said, I should certainly give a shout out to Mark Schilling’s focus on the director at the 2016 Udine Far East Film Festival, where the director received the Golden Mulberry Lifetime Achievement Award, while New York’s Japan Cuts festival (online, for obvious reasons this year) is celebrating Obayashi’s legacy.

The reason I’ve gone into Obayashi’s career in some depth is partly to commemorate a director whose passing at the age of 82 on 10th April 2020, went largely unnoticed by the British media. And in many ways, we might see Hanagatami as a culmination of his life in film. Obayashi had earmarked the source material, a novel of the same name (Hanagatami, incidentally, means “flower basket”) by Kazuo Dan (1912-1976), for adaptation around forty years ago. The decision to finally get underway came shortly after his 2016 visit to Udine, when he was diagnosed with stage-four lung cancer and given mere months to live.

It is remarkable not only that he saw Hanagatami all the way through to the cinema, but also that he still had enough fight in him to make another film of equal length, Labyrinth of Cinema, before he died. That final work has been, if anything, even more highly acclaimed since its premiere at Tokyo International Film Festival last November. Sadly, Obayashi did not live to see the more widespread nationwide release of his final work, which was postponed due to the coronavirus shutdown.

It is remarkable not only that he saw Hanagatami all the way through to the cinema, but also that he still had enough fight in him to make another film of equal length, Labyrinth of Cinema, before he died. That final work has been, if anything, even more highly acclaimed since its premiere at Tokyo International Film Festival last November. Sadly, Obayashi did not live to see the more widespread nationwide release of his final work, which was postponed due to the coronavirus shutdown.

Hanagatami’s air of wistful melancholy is established in the opening title cards that inform us that the novel it is based on was published in 1937, the year that Japan went to war with China. Aged just 25, the author Dan was himself drafted. He survived the war, although his wife Ritsuko succumbed to intestinal tuberculosis in 1946; her memory would be immortalised in a number of the author’s subsequent works bearing her name.

This background informs the film, set in the spring of 1941, prior to the attack on Pearl Harbor. We can see reflections of Dan and Obayashi in the character of Yamauchi, the long-haired teacher at the college where our protagonist Toshihiko is studying. The teacher’s advocation of the works of Osamu Dazai (a contemporary of Dan’s), Edgar Allan Poe, Vladimir Lenin and the filmmaker Sadao Yamanaka (who was also drafted) to his students hint at the dark psychosis looming over the nation, while the shearing of his bohemian locks when he his drafted at the midpoint of the film signals the fate awaiting them all.

Cherry blossoms abound in the happy-go-lucky Toshihiko’s world, however, a world of limpid full moons and herringbone sunsets unsullied by war. Separated from his parents in Amsterdam, due to his father’s military posting, his world is the small seaside setting of Karatsu, close to Fukuoka (where the author Dan was born), his classmates at the local boys college, and the home of his war-widow aunt Keiko, and her daughter Mina, a delicate ethereal beauty stricken with tuberculosis.

Obayashi’s overt sense of artifice and stylisation is immediately apparent in the superimposed cherry blossom showers that add an atmospheric ambience to his chimerical imagery, and the swirling blue ocean that meets the mountainous coastline, appearing as a back projection through windows of the Karatsu college classroom. Slow-motion sequences, momentary lapses in sound synchronisation and a slightly ghostly judder to the movements sometimes serve to conjure up a sense of a lost pre-war arcadia, as if it were another world, with the lurid colours and the theatricality of the performances adding to the air of exaggerated non-naturalism. Those familiar with the aesthetic of House might see the film’s amplified emotional register, with the sweeping doleful romanticism of the score that plays throughout, as akin to its expressionistic world of gothic horror.

Keiko’s bourgeois, Westernised family house overlooking the sea soon provides a base for Toshihiko and his peer group. There is Aso, the bumbling bespectacled class clown; Ukai, the dreamy, aloof loner and subject of Toshiyuki’s admiring gaze; and Kira, fatalistic, rationalist and abnormally divorced from his emotions, and whose relationship with Ukai is deep and complex due to two connected incidents involving a puppy and a tank of boiling water. The testosterone is tempered by the arrival of two female newcomers to join Mina: the perky and flirtatious Akine, who rapidly becomes smitten with Toshiyuki, and the more sullen and artistic Chitose, who has a secret history with Kira, and who performs as the photographic chronicler of this momentary youthful idyll of picnics and midnight swims.

Keiko’s bourgeois, Westernised family house overlooking the sea soon provides a base for Toshihiko and his peer group. There is Aso, the bumbling bespectacled class clown; Ukai, the dreamy, aloof loner and subject of Toshiyuki’s admiring gaze; and Kira, fatalistic, rationalist and abnormally divorced from his emotions, and whose relationship with Ukai is deep and complex due to two connected incidents involving a puppy and a tank of boiling water. The testosterone is tempered by the arrival of two female newcomers to join Mina: the perky and flirtatious Akine, who rapidly becomes smitten with Toshiyuki, and the more sullen and artistic Chitose, who has a secret history with Kira, and who performs as the photographic chronicler of this momentary youthful idyll of picnics and midnight swims.

“Why do we have wars while the world turns?” Mina ponders at one point, after she and Toshihiko sneak out to a secret hillock above the shoreline to go moon-gazing. “It’s like a half-awake dream”, Toshihiko muses, before the stolen kiss that will come to define a life, the moon reflected in the shifting hues of the light it casts across the rippling water behind them. Such hypnagogic magical realism is very much of the same strain of Obayashi’s early 16mm experimental works like Émotion (1966), an hommage to Roger Vadim’s Blood and Roses (1960), in which a possibly imaginary vampire figure intrudes into the emotional world of two young women vying over the same lover.

One also can’t help but be reminded of the work of Seijun Suzuki when watching Hanagatami – not only the Suzuki of Tokyo Drifter or Branded to Kill, nor even the exuberantly theatrical apogee of his swansong, Princess Raccoon (2005). This vivid and evocative depiction of the impetuosity and idealism of youth is reminiscent of Suzuki’s nostalgic triptych, shot in subdued monochrome and set in the days of his own youth in the 1920s and 1930s, consisting of The Incorrigible (1963), Born Under Crossed Stars (1965) and Fighting Elegy (1966), the last of these set in the years immediate running up to Obayashi’s film. Obayashi’s use of actors clearly playing at least a decade above their characters’ ages reinforces the comparison. The hypnotic, elliptical style and its evocation of a bygone age receding into an imagination beyond the mists of living memory, however, recalls the haunting fantastical worlds of Suzuki’s most personal work on ‘Taisho Trilogy’ of the 1980s. “Zigeunerweisen on acid” might be a trite way of describing Hanagatami, but it’s not entirely inaccurate.

If all of this sounds too overpowering, it should be noted that Obayashi’s handling of the tone and rhythms is virtuoso, with the subtle stylistic shifts between the film’s three chapters emblematic of his imagistic wizardry. The hyper-saturated lilacs, scarlets and peach-like oranges and ambers that predominate throughout the first act make way for the more melancholic nocturnal hues of the second, while the frostier, more muted palette sullied by violent splashes of scarlet in the increasingly fragmentary and delirious final section appear to consciously to evoke the Japanese flag in the run up to the inevitable emotional maelstrom

Hanagatami is a singular and astonishing cinematic achievement, with a poignant dreamlike aura about it that is never short of utterly bewitching, and Third Window should be commended for having the guts to release it. One awaits with bated breath to see whether Obayashi’s Labyrinth of Cinema will follow.

Jasper Sharp is the author of the Historical Dictionary of Japanese Cinema. Hanagatami is released in the UK by Third Window Films.

Leave a Reply