Ghibli on Vinyl

August 4, 2021 · 0 comments

By Andrew Osmond.

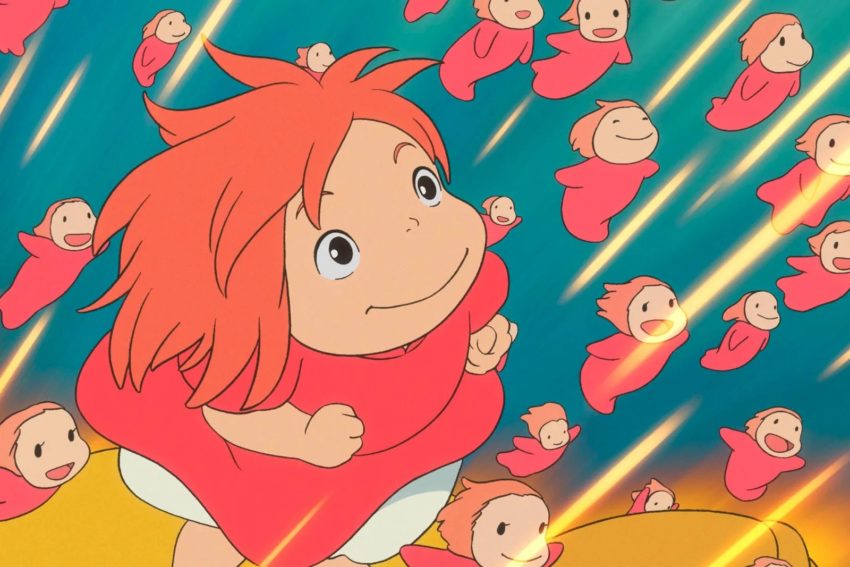

The treasure trove of Ghibli vinyl soundtracks released by Anime Limited represents the composer-director relationship in anime. Joe Hisaishi has written music for Hayao Miyazaki for nearly forty years. Whenever you watch Spirited Away, or Princess Mononoke, or Totoro, or Ponyo, you’re listening to Hisaishi’s evocations of Miyazaki’s vision.

Hisaishi was responsible for the firework trumpets in Totoro as the kids swoop round a new-grown camphor tree on a spinning top. He conceived the apocalyptic wails as a holy forest dies in Princess Mononoke, and the tranquil, yearning piano in Spirited Away, when a girl rides a train through a phantom world.

Like Miyazaki, Hisaishi is our guide to new worlds and a creator of those worlds. But Hisaishi is more than the Miyazaki composer. He’s released more than twenty personal albums, not counting compilations, dating to 1981. He’s written soundtracks to many live-action films, including seven collaborations with Takeshi Kitano. Many Westerners first encountered Hisaishi’s music not through Miyazaki’s films, but through Kitano’s feted crime films such as Hana-bi and Sonatine.

Hisaishi also scored the two Ni no Kuni videogames in the 2010s, composed the soundtrack for 1998’s winter Paralympics in Nagano, and has credits on non-Ghibli anime from Robot Carnival to the recent Children of the Sea. He’s produced orchestral music, electronic music, exercises in minimalism and avant-garde, a prodigious amount of piano work and plenty of rock and pop.

Unsurprisingly, he started music early. Born Mamoru Fujisawa in Nagano in 1950, he was studying the violin as a four-year-old. “There was no one reason for starting the violin,” he told the Kotaku website in 2020. “But when I was young, my father had a power gramophone that used bamboo needles. With that, I listened to lots of music, regardless of genre. My parents were not musicians, but in junior high school, I belonged to the brass band club, where I played the trumpet, trombone, saxophone, and even conducted as well.”

Joe Hisaishi is Fujisawa’s professional name, written “Hisaishi Joe” in Japanese. The Japanese pronunciation of “Hisaishi” is supposedly close to that of “Quincy”, a clue to why Fujisawa chose it. It’s a tribute to the African-American musician Quincy Jones, much as the fictional Gundam anti-hero Char Aznable was named after the French singer Charles Aznavour.

To stop confusion, let’s narrow down what is and isn’t by Hisaishi. He’s composed for all the Miyazaki-directed films since Nausicaa in 1984. Miyazaki’s previous Castle of Cagliostro was scored by Yuji Ohno, Lupin’s top composer, who created the character’s defining theme. Hisaishi also composed for Takahata’s final film, The Tale of the Princess Kaguya. However, he isn’t responsible for any of the other Ghibli films, many of which have outstanding scores too, such as Michio Mamiya’s music for Grave of the Fireflies, Yuji Nomi’s score for Whisper of the Heart, or Cecile Corbel’s work for Arrietty.

Also, Hisaishi wrote some of the opening and closing songs for Miyazaki’s films, but not all of them. The famous opening and closing songs for Totoro are definitely his, for example, along with the Ponyo earworm. So are the songs heard in Nausicaa, Laputa, Princess Mononoke – the ethereal countertenor piece sung by Yoshikazu Mera – and Howl.

Of the other songs, the two in Kiki and the beautiful number that ends The Wind Rises were existing works by the singer Yumi Matsutoya. In Disney’s dub of Kiki, Matsutoya’s songs were switched for two by the American singer Sydney Forest. The closing song in Porco Rosso was by Tokiko Kato, who voiced Gina in the film. The end song in Spirited Away was by Youmi Kimura, and the one in Kaguya was by Kazumi Nikaido.

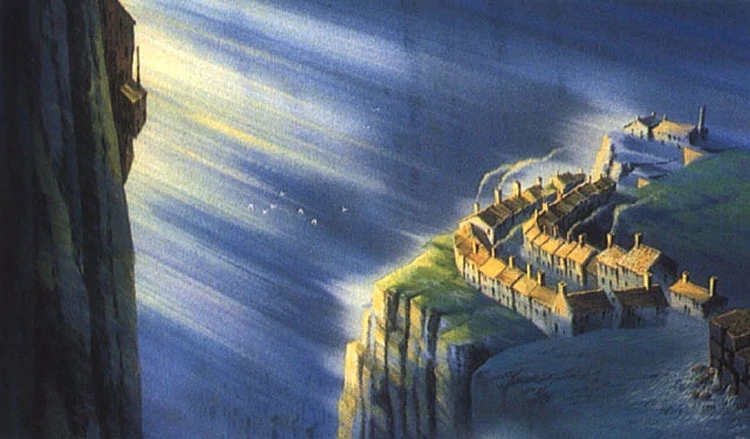

Additionally, Hisaishi’s own music for Kiki’s Delivery Service was adapted in Disney’s English dub by Paul Chihara, with extensive reorderings, additions and “enhancements.” The score for Laputa was also substantially changed and extended for Disney’s dub, but that new version was by Hisaishi himself, composed more than a decade after the original. I confess that I’ve never liked the “revised” Laputa score, with its obtrusively misplaced excesses; for example, when the children regard Laputa’s tree with its grave and buried robots.

Anime Limited’s vinyl releases will reflect the original Japanese soundtracks, though the “Image” and “Symphonic” albums contain Hisaishi’s alternative arrangements and developments of the films’ ideas, going past what’s heard on screen.

Talking to the online magazine Scorelogue, Hisaishi contrasted writing for Miyazaki with writing for Disney. “In Disney films,” Hisaishi explained, “in order to explain the type for each character, specific cues are married to their appearance. When I composed for the English version of Laputa, we actually did this Hollywood method so I understand the mechanics very well. The way I [normally] compose, however, is that none of my cues are necessarily married to any character. What I do instead is discern what the director is trying to convey in a scene and try to do the same with the music thematically.”

The most obvious thematic element is Hisaish’s sense of gentle innocence, especially in such film as Laputa, Totoro and Kiki. Think of the (Japanese) Laputa soundtrack as the children share a meal underground; the sisters racing through the house in Totoro; and the girl resting on the hill at the start of Kiki. The child-perspective is always the same, naive but not cloying. Actually, Hisaishi told Animerica, “I’m not much of an innocent… When it comes to a melody that’s supposed to be aspiring and gentle and embracing, I have a hard time of it.”

The second element of Hisaishi’s anime music is its sense of the magic, the holy. Examples include Mononoke’s startlingly beautiful “Encounter” theme when Ashitaka first sees the feral San. Then there’s the evocative New Age chimes as Porco Rosso encounters a ghostly fleet of planes. Child visions of the holy are suggested by the burst of music announcing the angelic Sheeta’s “landing” at the start of Laputa and the wait at Totoro’s bus-stop, when awesome woods and darkened shrines are seen through a nervous girl’s eyes. All the melodies in this paragraph have a lullaby quality. Both Sheeta’s introduction in Laputa and San’s in Mononoke involve harp music, giving those moments an ethereal texture.

The “holy” tag also applies, in different ways, to the poignant music as Kiki sees the painting Ursula has made of her – a more central moment than it sounds. Then there’s the child’s song when Nausicaa communes with the Ohmu. Child choruses also figure importantly in Laputa, making the connection between innocence and purity. Not that childish themes always have serious intent. A favourite anime song is the Hisaishi-scored “Sanpo” that opens Totoro, sung by an adult (Azumi Inoue) but an invitation for every child in the audience to join in. One mark of a true Ghibliophile is to be able to sing the lyrics in Japanese. “A-ru-ko, A-ru-ko, Watashi wa genki…” The words are by Rieko Nakagawa, but Hisaishi’s infectious melody is the thing.

Another Hisaishi trait can be described as his elegance. This is especially true of his more elegiac passages – think of the wanders through Nausicaa’s cleansed underworld and the ruins of Laputa, or the piano pieces underlying the forlorn relationships in Porco and (a non-Ghibli example) Robot Carnival’s “Presence.” The loveliest instance is also from Porco, as Gina recalls her first flight, a wonderful marriage of sound and picture. A close second is the requiem for Nausicaa, if you forgive its sampling of Leonard Bernstein’s “Somewhere” from West Side Story.

Jumping back to Nausicaa’s start, the pervasive electronic score after the film’s opening titles does more to establish the alien world than a dozen pages of dialogue. The soft notes blend with the chirps and cries of unfamiliar creatures, creating a complex soundscape. It’s an example of Hisaishi’s “minimalist” music. Early in his career, he was inspired by American composers such as Philip Glass and Terry Riley. In particular, Hisaishi has cited Riley’s 1969 piece, “A Rainbow in Curved Air”; its influence on Nausicaa is obvious.

“My base is still minimal music,” Hisaishi said as recently as 2015. “To express various scenes in a film I of course use melodious music but I also use a lot of minimalist approaches. In that sense I think of myself as a minimalist ultimately.” In his earlier Scorelogue interview, Hisaishi said, “I just happened to start out as a modern composer who was immersed in severe dissonant sounds for the longest time. I also happened to be allowed to compose some melodic pieces as well. In terms of being allowed to achieve this range, I believe (Takeshi) Kitano and Miyazaki just pulled it out of me.”

In Mononoke, the gorgeous music when Ashitaka first enters the kodama-haunted forest is the fruit of Hisaishi’s experimentation with the pentatonic scale, a five-note scale characteristic of traditional Japanese tunes and Irish folk-music. Human environments are represented by graceful orchestral pieces. Think of the music for Nausicaa’s valley home; dawn over Pazu’s village in Laputa; the jovial drive to the new house in Totoro; the flight to the city in Kiki; and the industrious female factory in Porco. As for Mononoke, the brief passage following Ashitaka’s welcome to Irontown suggests all those frontier towns in Hollywood Westerns.

Beyond these categorisations, there are so many pieces of music that are just plain good. My own favourites include the dynamic theme as Nausicaa escapes from the Pejite ship, dodging enemy bullets; all of the Laputa “rescue” sequence, from the powerful robot theme to Pazu’s catch of Sheeta; the mournful wonder of a wizard’s toy-strewn cave in Howl; the Wagner-spoofing empowerment as Ponyo sprints the waves; and the inhuman, shimmering beauty of Kaguya’s heavenly horde.

Then there’s Mei’s pursuit of the first Totoro (listen for the mini-melody with the butterfly). It’s one of Hisaishi’s best examples of “Mickey Mousing” the soundtrack. Another is the lovely, near-wordless sequence in Wind Rises, where Jiro throws paper planes for Naoko. It’s more elegant than the madcap Totoro, but has the same humour and buoyancy.

Then there’s Kiki’s metronomic bicycle; the anguished strings as Kaguya flees from her palace home; the exuberantly tumbling “Night-Time Coming” when darkness descends in Spirited Away; and the martial music when Porco comes ashore from Gina’s island. Then there are the majestic main themes for Laputa and Mononoke, and the playful waltz that defines the romance of Howl.

In 2020, Kotaku asked Hisaishi if he would be scoring Miyazaki’s upcoming film How Do You Live?, and if he had seen any footage from it. “No comment,” Hisaishi said.

Andrew Osmond is the author of 100 Animated Feature Films. The soundtracks of Studio Ghibli are being released on vinyl by Anime Limited.

Leave a Reply