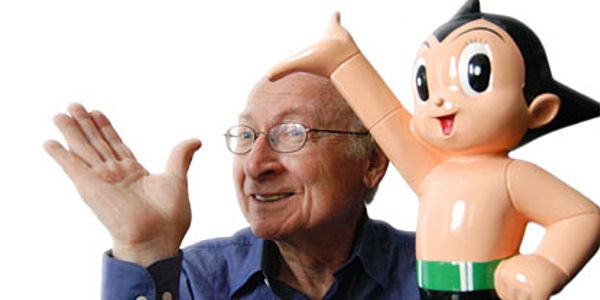

Fred Ladd (1927-2021)

August 15, 2021 · 2 comments

Fred Ladd, who died on 3rd August at the age of 94, met anime in 1963, when he was phoned by a New York company asking if there was potential in a foreign TV cartoon. The company was NBC Enterprises, a small outfit that rather hoped people would confuse it with the better known NBC channel. The foreign cartoon was Osamu Tezuka’s Tetsuwan Atom, about a hero boy robot. Ladd had a track record in localising foreign cartoons for America, but had never dealt with Japan.

In his memoir Astro Boy and Anime Come to the Americas, Ladd recalled how, after watching the cartoon’s first episode, he started thinking how it should be modified. He cited the very first scene. A boy, Tobio, is driving happily in his futuristic car when he’s involved in a fatal crash. Notably, Ladd thought the tragedy itself would be acceptable for American viewers. What concerned him is that in the original, Tobio is plainly driving carelessly. “It is difficult for an American audience to sympathise with a reckless driver,” Ladd wrote.

That’s why, in the Americanised Tetsuwan Atom, renamed Astro Boy, Ladd added voice-over narration to stipulate the car is being “steered” by the hi-tech highway. In other words, Tobio isn’t driving at all, and the accident is a terrible malfunction. Ladd’s version also removes the implausibility of a child driving a car. “American audiences sympathise with innocent victims; we can understand the father’s grief when his good son is lost in an accident that should never have happened,” Ladd wrote.

To today’s anime fans, this is like rewriting Fullmetal Alchemist so that the Elric brothers only try reviving their mum because they’re satanically possessed. It’s a point of honour among anime fans to condemn such “localised” adaptations. Three decades after Astro Boy, Ladd was involved in the DIC dub of Sailor Moon in 1995. He loved its characters, how human they felt, but he was “astounded to see cruelty to children portrayed so graphically in what was, in fact, a kids’ show.” That put Ladd at loggerheads with what he described as “cadres of highly vocal fans” who’d seen the original anime.

Ladd, though, had been around when foreign, non-Anglophone media was a new frontier. He was born Fred Laderman in the city of Toledo in Ohio in 1927 – one year before the birth of Astro Boy’s creator, Tezuka. From childhood, Ladd was fascinated by animation. He didn’t just do impressions of Mickey Mouse and Betty Boop; he hoped he could write for animation one day, but not draw it: “I can draw stick figures, nothing more.”

Although Ladd’s university degree was in radio programming, by the 1950s he was working in an advertising agency and writing commercials animated by Shamus Culhane Productions, founded by the eponymous Hollywood animator. (There are examples of the studio’s commercials here.) However, Ladd’s first experience of buying foreign media was in live action. He purchased stock footage of wild animals, which was compiled into a nature documentary series called Jungle.

That series was shown in Europe. “At that time,” Ladd said, “some of the countries has blocked funds (their dollars could not be exported), so we took the payment in the form of animated cartoons – in effect, barter. That’s when I had to learn how to dub, in a hurry!” These weren’t Japanese cartoons, but European ones. Many were cut into five-minute segments and shown on TV under the heading Cartoon Classics, which ran to over 300 episodes.

A more complex case was The Space Explorers (trailer) distributed as both a film and serial, which mixed footage from three different films, two Russian and one German. It’s a precursor of sorts to the likes of Robotech (which didn’t involve Ladd).

When Ladd first encountered Astro Boy, he was in the middle of work on an American-European cartoon film, animated in Brussels. It was called Pinocchio in Outer Space, on which Ladd was the producer and writer. Coincidentally, it paralleled Japanese cartoon films of the time – it came out in 1965, the year Toei’s Gulliver’s Travels Beyond the Moon opened in Japan. Also, as Ladd noted, his Pinocchio film featured a character called Astro – a flying space whale!

Ladd dubbed Astro Boy for the American market at the Titra Sound Studios on Broadway. He recalls the first English translations he received from Tezuka’s Mushi studio were hard to understand – “I actually checked a globe looking for the Himiraya Mountains, before realising that many Japanese pronounce an L as an R.” Ladd’s dub cast consisted of just three actors, Billie Lou Watt (who voiced Astro Boy), Gilbert Mack and Cliff Owens. The dubs were created at breakneck speed but with, Ladd remembered, a warm camaraderie between the tiny team.

Ladd’s “localising” approach was vindicated early. Of the first batch of Tetsuwan Atom episodes sent by Mushi, six were rejected for broadcast by NBC. Consequently, Ladd flew to Japan in 1964, at the end of the city’s Olympics, to meet Tezuka in person. Ladd recalled that at first Tezuka suspected he was a spy for NBC, but the artist warmed up quickly when he realised Ladd wanted to support his creation. For his part, Ladd explained NBC could not accept, for example, an episode about vivisection, or a story where a criminal hides in a church and scratches a message on the eyeball of a Christ figurine.

The dubbed Astro Boy was a ratings hit in America, and Ladd was soon involved in further anime imports. He adapted the English-language “pilot” of 8th Man, though the full series was dubbed in Florida by other hands. He then became involved with another robot series, Tetsujin 28, renamed Gigantor in America. As NBC Enterprises wasn’t interested in the show, Ladd and his business partner Al Singer formed their own corporation to handle it, Delphi Associates.

The Japanese Tetsujin 28 included multi-part stories, but that was unacceptable for a series being syndicated to American stations, which might show them in any order. Consequently, Ladd worked with the anime studio, TCJ, to re-shoot parts of the episodes. Ladd recalled, “We were replacing TCJ’s cliffhanger ending with our own new ending… Every Gigantor programme that was originally ‘To Be Continued’ comes to its own natural end.”

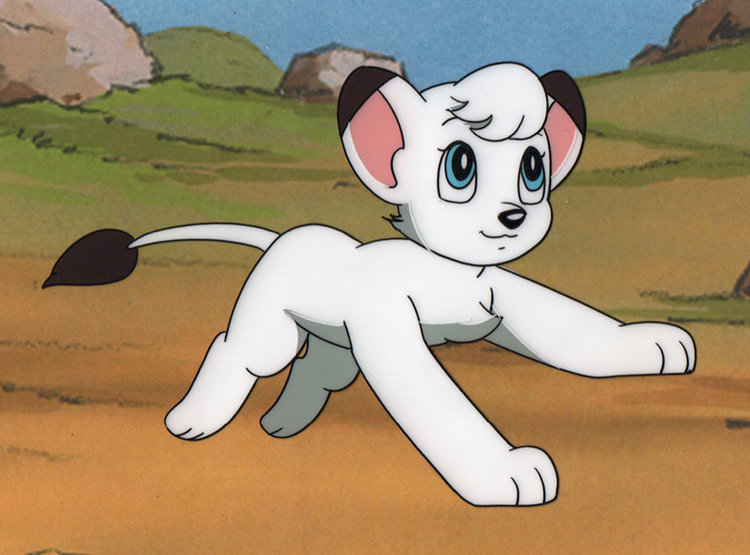

Ladd then handled Kimba the White Lion for NBC. This was the dub of Tezuka’s first colour series, Jungle Emperor. Ladd originally pushed for the lion – Leo in the original – to be named Simba, the Swahili word for lion, as he thought it sounded strong and virile. However, the name was turned down as too generic for merchandising, hence “Kimba,” though Ladd disliked it. Decades later, Ladd supported the argument that Kimba plainly inspired a hero called Simba – that is, Disney’s Lion King.

Following Kimba, Ladd tried to interest NBC in Tatsunoko’s anime Space Ace. While this had been made in black and white in Japan, Tatsunoko re-rendered an episode in colour for the American pitch. NBC turned it down, but this foreshadowed a huge project for Ladd in the late 1960s and into the 1970s – colorising vintage Hollywood cartoons, to be shown on American television.

Ladd worked with companies in Seoul, converting hundreds of monochrome toons starring the likes of Porky Pig, Krazy Kat and Popeye. One Japanese cartoon converted this way was Tezuka’s 1965 film of Treasure Island. The Anime Encyclopedia notes that the Seoul colourists “ensured that it was the South Korean flag, not the Japanese one, that the animals accidentally raise in a throwaway gag.” By Ladd’s account, these projects caused a surge in animation in South Korea, and helped the country become a sub-contracted powerhouse for cartoons round the world.

Ladd was also involved in matchmaking anime studios with dub outfits for projects he couldn’t do himself, as was the case with Marine Boy and Speed Racer – Ladd called the latter “The Big One that got away.” In the 1970s, however, Ladd handled the dubs of three cinema anime films by Toei, though he himself argued they weren’t anime; he reserved the term for TV and video productions. The films were the seminal The Little Norse Prince, directed by Isao Takahata, and the comedies Puss in Boots and Animal Treasure Island (not to be confused with Tezuka’s Treasure Island).

Of such titles, Ladd said, “Japanese timing is remarkably – and surprisingly – like American timing. I could see that in Tezuka’s first anime series in 1963. I saw it again in the three Toei features… Whereas European animators time their on-screen actions somewhat slowly, introspectively, the Japanese pace their animated movies much faster – with zip and verve! That may help explain why anime has become so popular in the West. With snappy English dialogue applied in the dubbing process, a Japanese cartoon can look and sound as though it were made entirely in Hollywood.”

Also in the 1970s, Ladd was offered the job of dubbing Battle of the Planets, Sandy Frank’s version of Tatsunoko’s Gatchaman. He turned it down on hearing that it would be scripted by an animator with no lip-sync dub experience. In the 1980s, though, Ladd would handle an alternative dub of Gatchaman, Turner Broadcasting’s G-Force: Guardians of Space.

Ladd also racked up credits on non-anime cartoons. He co-wrote and co-produced the 1972 musical feature Journey Back to Oz, in which Dorothy was voiced by Judy Garland’s daughter, Liza Minnelli. In fact, Ladd worked on this long-gestating film back in the 1960s, and used some of the recording techniques he picked up to help dub the singing animals in Kimba.

In the 1980s, Ladd wrote for TV cartoons including MASK and The Incredible Hulk. On the anime side, he dubbed religious-themed series by Video Japonica, which were released in America as Bible Stories: Tales from the Old Testament and The Life of Buddha. Into the 1990s, Ladd was revisiting an old robot friend, dubbing the colour series The New Adventures of Gigantor. He was also brought onto the DIC version of Sailor Moon, taking over from another legend of localisation, Robotech’s Carl Macek.

By then, Ladd already knew about anime fans, while those fans recognised him as a key pioneer. Ladd would recall, “More than once, as a visitor to (an anime club) meeting, I found myself in a Q and A session, being asked questions about matters in which the fans were far more knowledgeable than I – they remembered details in my scripts that I, myself, had forgotten!”

Asked if he preferred old or new anime, Ladd was unequivocal. “I prefer the old series… not because of nostalgia or because the original old stories were shot in artsy black and white, but because the older shows were character-driven… Now the shows that I see coming from Tokyo are driven largely by merchandise – trading cards and video games and variations thereof. Story seems to have taken a backseat to merchandise.”

Jennifer

August 24, 2021 8:24 am

Thank you, Andrew Osmond, for your fine-honed posting about Fred Ladd. Very much appreciated.

Andrew Osmond

August 27, 2021 8:27 am

I'm very glad you liked it!