Blind Beast

October 21, 2021 · 0 comments

By Tom Wilmot.

As the 1960s wore on, Japanese filmmaker Yasuzo Masumura survived in a studio system in decline. Financial strictures meant that the director’s projects had scaled down in recent years, though the cinematic explorations at the core of his work remained in sharp focus. A prime example of this is his 1969 film, Blind Beast, which is now made available on Blu-ray through the folks at Arrow Video. While not quite a late career masterpiece, this adaptation of famed author Edogawa Rampo’s novel certainly marks a high point in Masumura’s filmography, refining many of the hallmarks that have since become synonymous with his work.

Aki (Mako Midori) is a young nude model who, after a brief encounter at an art gallery, is kidnapped by the obsessive and blind Michio (Eiji Funakoshi). A passionate sculptor, Michio is fixated on Aki’s body, which he can feel intimately through his enhanced sense of touch. Trapped in the twisted artist’s workshop, Aki desperately tries to escape both Michio and his mother (Noriko Sengoku), while the self-proclaimed artist attempts to sculpt her figure and bring to life a new art form.

The Daiei studio production model saw many films based on literary works given the green light, and this approach, as well as the studio’s aim to lure in audiences with more risqué content, is how Blind Beast came into being. Initially serialised in the Asahi national newspaper between 1931 and 1932, “Moju: The Blind Beast” was written by the highly influential Edogawa Rampo and can be categorised, along with many of the author’s other works, under the bracket of ero guro nansensu (erotic grotesque nonsense). Masumura’s film is just one of many silver-screen adaptations of Rampo’s works, though it’s perhaps the one that captures the perverse nature of his extreme stories most accurately. The director’s focus on sexuality had intensified throughout the sixties, with explicit endeavours such as Irezumi (1966) and Red Angel (1966) marking darker explorations of sensuality. Thus, the pairing of Masumura’s intimate direction with Rampo’s shocking erotica proves to be a match made in heaven, as Blind Beast is the perfect storm.

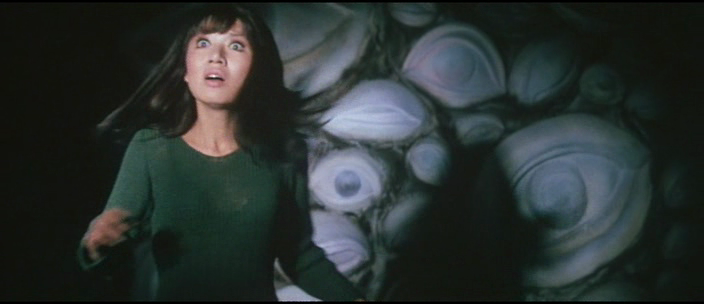

Significant financial constraints were placed on Masumura for the film’s production, though you’d find this hard to believe given the quite magnificent set design. The demented collage of sculptured female body parts that fill Michio’s workshop makes for a hellscape that is instantly recognisable. The work of art director Shigeo Mano is phenomenal, with the surreal statues being a major part of what makes the film an almost hallucinatory experience at times. The way that this space is initially lit is brilliant, with each twisted wall getting its own special reveal. The eventual unveiling of the two giant, naked sculptures in the middle of the workshop completes the disorienting décor of this isolated chamber of insanity. That Masumura’s initial grand vision of a larger workshop could not be realised is a shame, although it must be said that Blind Beast’s enclosed setting does induce a strong feeling of claustrophobia.

Anyone familiar with Masumura’s work will note that Blind Beast does not share the excesses displayed in his earlier films, such as Giants and Toys (1958). From the small cast of only three actors to the restricted setting, it’s a testament to the director’s versatility that the film is consistently varied in its visuals. Much in the same way that the limited space does wonders for the isolated atmosphere, the scaled-down narrative lets Masumura hone in on familiar cinematic themes with greater intensity. His examination of sexuality as a tool is prominent here, as the director toys with the power balance between the sensually obsessed Michio and an increasingly desperate Aki. The way Aki feigns physical affection to gain control over Michio falls in line with Masumura’s previous depictions of female characters who become empowered through their sexual hold over others. Where Blind Beast goes one step further compared to the director’s prior work is with the deep dive into sadomasochism that dominates the final act. The cringe-inducing finale borders on the comical in moments, though its study of sexual taboos and the limits of physical pleasure makes for a fascinating exercise in debauchery.

The only thing missing from Blind Beast to make it a complete Masumura film is the gracious presence of Ayako Wakao, who was so often the director’s muse. Her absence paves the way for the fantastic and relatively fresh-faced Mako Midori to take the role of Aki. Making her screen debut some six years earlier, Midori had worked with, and greatly impressed, Masumura once before on his 1968 film The Great Villains. Her casting proves an inspired choice, as where Wakao’s depiction of such a sensual character might have been overly familiar to audiences, Midori injects a touch of wild energy into the role. Opposite Midori is the always excellent Masumura and Daiei regular Eiji Funakoshi, who’s somewhat cast against type as the frightening Michio. One can look deeper into Michio’s madness and say it captures the image of a misunderstood artist who is desperate to bring people around to his way of seeing beauty. When looked at through this lens, there are clear parallels between Michio and the iconoclast that is Masumura – a defiant member of the studio system tearing down the traditional ideals of Japanese cinema.

Offering a comprehensive introduction to both the film and Masumura is Japanese cinema expert Tony Rayns, whose knowledge of the director seemingly knows no bounds. The Sight & Sound writer provides extensive background on Masumura in an accessible manner, discussing everything from his European influences to early filmmaking experiences. On the subject of Daiei, Rayns outlines the dire financial situation faced by the studio in the late 1960s, which was partly responsible for the production of “disreputable” films that would generate notoriety. Rayns’ interpretation of Blind Beast as a Masumura re-reading of the original Rampo novel is an astute one, with the commentator arguing that the film lends itself to the director’s typical focus on female empowerment.

Fulfilling the audio commentary duties for this Arrow release is Asian cinema scholar Earl Jackson, who takes an analytical approach. Extensive breakdowns of specific scenes, notably Aki’s awakening in Michio’s twisted workshop, provide valuable insight into Masumura’s directorial process and subtle storytelling. There’s a lot of information to take in here, as Jackson zips through interesting snippets on the film’s three actors, the vital role of gender in Masumura’s films, and screenwriter Yoshio Shirasaka’s approach to adapting literary works.

The sensuality at the centre of the narrative is explored at length by Japanese literature and visual studies expert Seth Jacobowitz in his accompanying video essay. The scholar raises the question of whether Michio should be considered a monster or an aesthetic genius, though it would take some convincing to be assured that the would-be sculptor isn’t out of his mind. Jackobwitz’s comments are complemented by an enthralling written essay by Dr Virginie Sélavy. The Electric Sheep magazine founder makes a compelling argument that Blind Beast is a further example of Masumura’s cinema showing the liberation of its subjects from the various pressures of Japanese society. Sélavy’s refreshing reading of the director’s films offers yet another perspective on his diverse body of work.

It’s easy to see Blind Beast as a culmination of Yasuzo Masumura’s filmography throughout the 1960s. It isolates the key focal points of the director’s more sexually charged films, those being obsession, perversion, and control, and blends them into a sensory experience like no other. While not as shocking as it undoubtedly was upon release, the film nonetheless raises uncomfortable questions concerning the limits of sexual desire, which are presented in a strikingly surrealist manner. For those keen to delve further into Masumura work, Blind Beast is essential viewing. Even in the broader realm of Japanese fantasy-horror and erotic cinema, the film is a landmark piece that deserves to be re-visited.

Blind Beast is released in the UK by Arrow Video.

Leave a Reply