Books: Art of Castle in the Sky

December 29, 2016 · 0 comments

By Andrew Osmond.

The Art of Castle in the Sky may be the final large-format Ghibli art book to be translated into English… at least for a while. Over the years, the art books for all Miyazaki’s films from Totoro onward have been published by VIZ Media (the Wind Rises book came out in 2014). The Japanese Art of Nausicaa hasn’t been done, but VIZ chose to translate the lovely Nausicaa Watercolor Impressions instead, adding “The Art of” to the cover of the English edition.

The Art of Castle in the Sky may be the final large-format Ghibli art book to be translated into English… at least for a while. Over the years, the art books for all Miyazaki’s films from Totoro onward have been published by VIZ Media (the Wind Rises book came out in 2014). The Japanese Art of Nausicaa hasn’t been done, but VIZ chose to translate the lovely Nausicaa Watercolor Impressions instead, adding “The Art of” to the cover of the English edition.

Of course, it’s possible that having done all the Miyazaki titles, VIZ may turn to other Ghibli films. So far, it’s only tackled Arrietty, but several more films have had sturdy art books in Japanese, including Oscar nominees Princess Kaguya and When Marnie Was There. Less likely (but we can dream), there are the Japanese “Roman Album” books for the Ghibli films. They’re not as picture heavy as the Art Books, but are full of staff interviews and other invaluable info.

When I wrote my own small book on Spirited Away, some kind Japanese friends translated parts of that film’s Roman Album for me, which had real revelations. However, translating such a text-heavy book from Japanese might be prohibitively difficult for Viz, given the presumably modest market.

When I wrote my own small book on Spirited Away, some kind Japanese friends translated parts of that film’s Roman Album for me, which had real revelations. However, translating such a text-heavy book from Japanese might be prohibitively difficult for Viz, given the presumably modest market.

I was delighted, though, to see The Art of Castle in the Sky, based on my own favourite Miyazaki film. I’m guessing anyone reading this review already knows the film itself, and probably why this US edition doesn’t have “Laputa” on the cover (if not, see here). The best steampunk film ever, Laputa’s influence lingers in films like Yasuhiro Yoshiura’s Patema Inverted (which Yoshiura described as his venture into “the world of Laputa and the boy-meets-girl story”) and the excellent French cartoon April and the Extraordinary World. Oh, and Laputa is the favourite animation of Makoto Shinaki.

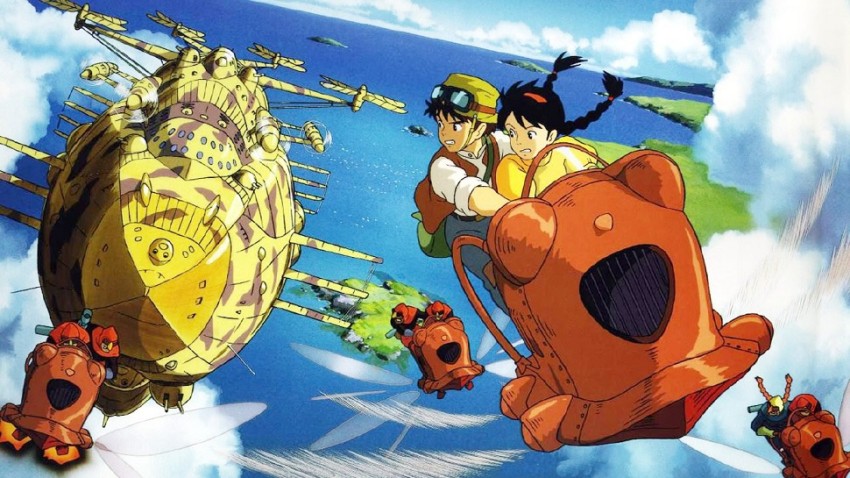

If you’ve bought any of the other Ghibli art books, then Laputa follows the same form – hundreds of stills from the film, plus a fair number of other drawings. Some of the pages break a moment of animation into its individual frames – for example, Pazu catching the floating Sheeta at the start (and then being staggered by her weight), or the kids using the levitation crystal together to float to safety. The cartoony fight in the town gets two pages, with Miyazaki saying he pushed the animator, Yoshinori Kanada, to make the scene more reckless and “manga-like.”

Conversely, there are a few near- or full-page images showing off backgrounds, such as the brief, sublime glimpse of much of Laputa’s castle-city submerged underwater. Other stills are postcard sized. All the pics are arranged in chronological order, roughly like a comic strip, though with no speech-bubbles and the explanatory captions tucked away neatly at the sides.

As usual, though, it’s the preparatory drawings, not the stills, which are most interesting. We get blueprints for the flying machines, of course. The pirate ship Tiger Moth once resembled a giant Laputan robot; Laputa itself would have once consisted of two castles, one stuck upside-down on the bottom. As for the characters, Pazu seems to have always looked like Pazu, barring a drawing where he dresses like Ma Dola’s sky-pirates. Sheeta, though, went through a range of possible looks.

One version is close to Lana in Miyazaki’s 1970s series Future Boy Conan. Other sketches show Sheeta as a blond with a Princess Leia hairdo. Yet another drawing gives her orange-red hair and a red dress, described as “the daughter of pirates” – perhaps Miyazaki was thinking of characters like Kathy in Animal Treasure Island and Tera in Future Boy Conan. He commented he wanted to make Sheeta solidly built (with, we learn, heavy thighs!), hence perhaps the joke about Pazu misjudging her weight. Oh, and if you’re wondering, her name comes from the Greek letter “theta.”

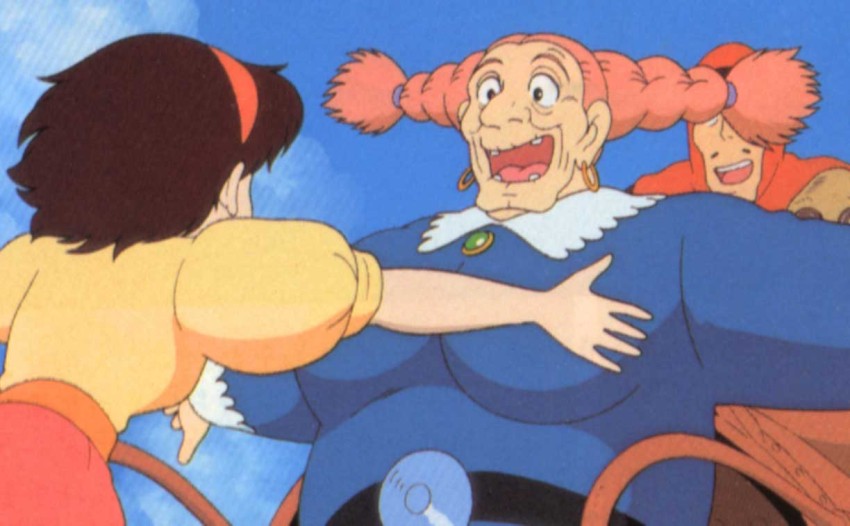

Of the adults, the pirate queen Ma Dola is described by Miyazaki thus: “Rather than the warm, kind mom figure, she’s the sort of mother who’ll give a bad kid a kick and do what she can to help if she seems something in you… Unparalleled appetite, magnificent greed, robust good health.” Meanwhile Muska is contrasted with Miyazaki’s previous villains. “Lepka (the heavy in Future Boy Conan) and Cagliostro (in Castle of Cagliostro) are, in a sense, complete men. In contrast, it seems to me that Muska is not quite finished… I settled on a longer, thinner, sort of vegetal face.”

The book has many evocative concept sketches of particular scenes, but more striking are the illustrations Miyazaki drew for a Japanese novelisation of the film. They’re very close to the on-screen images, but with an extra level of hand-drawn and shaded delicacy. It’s like glimpsing images from an alternative cartoon of Laputa, close to some of the work by Richard Williams.

There’s an interesting discussion of the problems animating the “flaptors,” the pirates’ zippy mini-flying vessels with buzzing insect wings. The text is slightly confusing – two sentences seem contradictory – but the upshot is plain. After trial and error, the only way that the artists could convey the buzzing wings was by smudging images with a dry brush and then using “tricks,” such as stopping the wings momentarily, to convey how the machine flew. One wonders if CGI would have made this easier, or if it would have created a synthetic object, spoiling the look of the film.

As for smaller bits of info, there’s an abundance of them. We learn, for example, that Uncle Pom – the old, solitary miner – was an amalgam of two great animators, Yoshifumi Kondo (the future director of Whisper of the Heart) and Yasuji Mori (a legend of Toei animation and Miyazaki’s mentor). Miyazaki: “The personality of Pom is that he’s shy in front of people and can’t talk. He’s someone who would rather spend time with the rocks underground than talk with people.”

Other info-bites include the revelation that Miyazaki was tempted to skip Pazu playing his trumpet reveille at sunrise, but was persuaded to keep it by Osamu Kameoka, author of the novelisation (the heroine of Your Lie in April plays the same tune in the series’ first episode.) One scene Miyazaki did tighten was the prologue on the airship. Originally he’d considered a chase where Sheeta clambers over the structure of the vessel, trying to evade the pirates. But he decided this was dawdling; “She’s going to fall anyway, so I ended up just having her go on and fall!”

On the same page, we learn Miyazaki hadn’t intended “Slag Ravine,” Pazu’s mining home, to be as deep and massive as it turned out. That was down to a female layout artist, Toshiro Nozaki. “I had been thinking of something a little gentler,” Miyazaki reveals, “but then I felt like this was good the way it was.” The book also points up obvious things you might have missed. I’ve seen the film umpteen times without registering that Pazu had built his hut on a disused stone blast furnace.

One disappointment is that there’s very little in the book about Miyazaki’s research visit to Wales which helped inspire the early scenes. But we do learn that Slag Ravine wasn’t just Wales; the town streets were informed by Miyazaki’s research on English houses for his series Sherlock Hound. In addition, when Pazu buys supper in his first scene, the shop is shown with an outside hearth, based on one Miyazaki had seen in China.

One disappointment is that there’s very little in the book about Miyazaki’s research visit to Wales which helped inspire the early scenes. But we do learn that Slag Ravine wasn’t just Wales; the town streets were informed by Miyazaki’s research on English houses for his series Sherlock Hound. In addition, when Pazu buys supper in his first scene, the shop is shown with an outside hearth, based on one Miyazaki had seen in China.

The opening pages are especially informative. The Nausicaa Watercolor Impressions book mentions Miyazaki had had a flying castle idea for a long time – there’s one in a sketch he drew in the early 1980s, before Nausicaa. Yet Laputa was apparently nowhere in his thoughts when Nausicaa was released. Miyazaki was perplexed by what he’d made – for example, he disliked Nausicaa’s religion-tinged ending, but many of the film’s fans loved it.

For a while after Nausicaa, Miyazaki tried sketching out a film to be directed by Takahata – a teen drama set in Yanagawa, a Kyushu city famed for its canals. In broad outlines, it resembles From Up on Poppy Hill – indeed, it’s possible Miyazaki had already read the source manga. As in Poppy Hill, the emerging story centres around a historical mystery; a lost canal, tied in with the secret of a beautiful girl’s birth. Some Ghibli fans may have already guessed what became of the project. It transmogrified into a live-action, non-fiction documentary, directed by Takahata, called The Story of Yanagawa’s Canals.

There were other possibilities for animation, though. Miyazaki recommended his colleagues to read British children’s books like Minnow on the Say by Philippa Pearce, about two boys seeking treasure in Cambridgeshire, and Colonel Sheperton’s Clock, an adventure story by Philip Turner. Around this time, the new Ghibli studio also sought the rights to an American fantasy, Ursula Le Guin’s Earthsea, without success.

Miyazaki was also cooking up more story ideas – a “Princess Mononoke” story very different from the eventual film (details); a Sengoku period drama; and an odd idea called My Neighbor Totoro. But the Sengoku idea would have meant finding artists who could animate horses, a tough call. Totoro was judged “a bit mellow” and possibly too sharp a contrast with Nausicaa. This was the time when Ghibli’s parent company, Tokuma Shoten, was keen on Miyazaki making Nausicaa Part 2.

In the end, Miyazaki plumped for making, in his words, “Treasure Island (in the sense of an adventure story with girls and boys).” His proposal specifies a film aimed at elementary fourth graders – he’d been surprised to see kids that age going to Nausicaa, which he’d meant for older viewers. He also commented on the place of an old-school adventure story. Miyazaki described Laputa as a contrast to “serious, dramatic gekiga comics,” saying it would aim to “help resurrect traditionally entertaining manga- or cartoon-style films.”

This connects to Miyazaki’s concerns about the way anime was going in the mid-1980s. “The future of animation is threatened by the fact that for most films being planned today, the target age is gradually creeping upward. More and more animated films are being made to cater to niche interests…” Writing in late-1984, Miyazaki may have been thinking of Macross: Do You Remember Love? and upcoming films like The Dagger of Kamui and Vampire Hunter D.

“It is important for us not to lose sight of the fact that animation should above all belong to children,” Miyazaki proclaimed, “and that truly honest works for children will also succeed with adults. Pazu [the film’s name wasn’t settled] is a project to bring animation back to its roots.” As for otaku, the kind of people reading his continuing Nausicaa strip in Animage magazine, Miyazaki was blithe about them. “I am certain that hundreds of thousands of older anime fans will come to see this film no matter what, so there is no need to overtly cater to their tastes.”

Yet Miyazaki later said he failed in some of his ambitions. When he finished the Laputa script, he commented, “I’ve long thought I wanted to make an old-school adventure story, but the era we’re in now, it’s no longer possible.” It seems Miyazaki thought this because of how his story ends, with Laputa revealed to be no simple treasure island. His comments are strange for anyone, like me, who thinks of Laputa as a quintessentially old-school adventure. But then, the author of the original Treasure Island wasn’t sure if such yarns resonated in “modern” times, and that was a century earlier! (Read RL Stevenson’s epigraph to his novel here.)

By the way, the Toei company conducted a survey to find out who saw Laputa in the cinema in Japan. It reported that the audience was two-thirds male, one-third female… and that the average age of the viewers was nineteen.

The Art of Castle in the Sky is out now.

Leave a Reply