Akio Jissoji: The Buddhist Trilogy

September 3, 2019 · 1 comment

By Jasper Sharp.

It is a ballsy act for a company to put out a four-film box set of titles made almost half a century ago that have never had any form of home video release outside Japan, all made by a director whose name is unknown outside the rarefied circles of Japanese film specialism. This is, however, exactly what Arrow has done with the much-anticipated, long-delayed release of Akio Jissoji: The Buddhist Trilogy on its Arrow Academy sub-label, devoted to bringing “cinephiles prestige editions of new and classic films from the greatest filmmakers across the globe.”

It is a ballsy act for a company to put out a four-film box set of titles made almost half a century ago that have never had any form of home video release outside Japan, all made by a director whose name is unknown outside the rarefied circles of Japanese film specialism. This is, however, exactly what Arrow has done with the much-anticipated, long-delayed release of Akio Jissoji: The Buddhist Trilogy on its Arrow Academy sub-label, devoted to bringing “cinephiles prestige editions of new and classic films from the greatest filmmakers across the globe.”

Although packaged as a trilogy, there are actually four films, here. The original collection of This Transient Life (1970), Mandala (1971) and Poem (1972) was originally scheduled for June 2018, but Arrow has more than generously atoned for the year-long hold up (due to issues licensing the HD masters) by adding a fourth title, It Was a Faint Dream (1974).

Furthermore, this isn’t exactly the first time any of the films have been seen outside Japan. This Transient Life won the Golden Leopard at the Locarno International Film Festival at the time of its original release. More recently, it was included within the programme of a 2011 retrospective at the British Film Institute dedicated to The Art Theatre Guild of Japan, or ATG, the idealistic distribution-production company that sustained art-house cinema in Japan for several decades following its establishment in the early 1960s. That said, the point remains that up until now the films have been effectively unavailable for closer scrutiny.

And then there’s the director himself. The name of Jissoji is one that seems to pop up in a number of markedly different contexts, which has tended to give the impression of him as a man in the margins, a director whose seemingly scatter-shot yet surprisingly small output makes him a remarkably difficult one to pin down to any one filmmaking environment or movement.

The two Jissoji films that have thus far reached home-viewing markets outside Japan have been ArtsMagic’s DVD of Tokyo: The Last Megalopolis (1988), a sprawling apocalyptic sci-fi fantasy set during an alternate Taisho era (1912-26) featuring art design by the legendary H. R. Giger and career comebacks from the 1960s cult performers Shintaro ‘Zatoichi’ Katsu and Jo Shishido, and Mondo Macabro’s release of Prosperities of Vice (1988), an adaptation of the Marquis de Sade transplanted to 1920s Japan. The former was one of the biggest-budgeted spectacles the industry turned out during Japan’s bubble decade. The latter, released a mere six months later, was a low-budget erotic film released by Nikkatsu shortly after the discontinuation of its Roman Porno adult line.

What the two works did share was their setting in an era often viewed as Japan’s belle époque, also evoked for Jissoji’s subsequent adaptations of the celebrated mystery writer Edogawa Rampo, Watcher in the Attic (1994) and Murder on D Street (1998), suggesting a fascination with the kind of decadence and musty eroticism that this interwar period came to symbolise. Interestingly, by this point the director a well-known enough name in his homeland to endorse a four-tape straight-to-video anthology series released by Bandai Visual across 1992 entitled Akio Jissoji’s Mystery Mansion.

But then, just as you think you are getting some sort of grip on Jissoji’s persistency of vision, you realise that not only did he cut his teeth working alongside Godzilla SFX maestro Eiji Tsuburaya creating such seminal tokusatsu TV series as Ultraman, Ultra Q and Ultra Seven in the late 1960s, but that his association with this kind of material persisted across the subsequent decades. Jissoji helmed theatrical outings of Ultraman in 1979 and Ultra Q in 1990, and just prior to his final directing credit for the first section on the portmanteau of Natsume Soseki stories, Ten Nights of Dreams (2006), he is credited as direction supervisor on that legendary low-fi tokusatsu takedown, Calamari Wrestler (2004). When he passed away due to stomach cancer in 2006, aged 69, he was working on a new movie version of Silver Mask, based on the kids TV show that first aired around the time of the releases of the initial films in his Buddhist trilogy (it was completed by Mitsunori Hattori).

The notion of parallel tracks in the career of a man who is also known as a passionate train buff in Japan seems apt (he appeared in a documentary on the subject in 2001). However, the lack of availability of these key early-career titles up to this Arrow release has left an enigmatic absence with which to link the seemingly disparate aspects of Jissoji’s filmography. The Buddhist Trilogy is therefore welcome in throwing the rest of this output into relief, proof that there is more to Jissoji than rubber-suited TV superheroes and sexed-up adaptations of Taisho-era penny dreadfuls.

The notion of parallel tracks in the career of a man who is also known as a passionate train buff in Japan seems apt (he appeared in a documentary on the subject in 2001). However, the lack of availability of these key early-career titles up to this Arrow release has left an enigmatic absence with which to link the seemingly disparate aspects of Jissoji’s filmography. The Buddhist Trilogy is therefore welcome in throwing the rest of this output into relief, proof that there is more to Jissoji than rubber-suited TV superheroes and sexed-up adaptations of Taisho-era penny dreadfuls.

Themes of impermanence, physicality, carnality, suffering and desire infuse the four films in the package. Though a late addition, It Was a Faint Dream sits comfortably alongside the ‘official’ trilogy – although it is not exactly clear whether the other three films were originally seen in Japan as representing a trilogy as such, or whether this grouping has been imposed retroactively. What we can say is that all of the titles can be described as elliptical, experimental and thoroughly odd: none markedly more so than any of the others, and yet all with a feel quite distinctly different from one another.

If the synopses of the films are as vague in Arrow’s packaging and promotion of the set as they have been in the rare instances of previous writing about them, it is undoubtedly because the titles in question don’t lend themselves well to synopsising. For example, Roland Domenig’s description of This Transient Life in the catalogue for the 2003 ATG retrospective he curated in Vienna (which formed the basis of subsequent programmes elsewhere such as the aforementioned BFI season in 2011) merely claims “it explores the bedrock of the Japanese psyche and ponders the questions of what happens to a person when Buddhist suffering and sexual desire merge”, without mentioning the film’s focus on the taboo of incest.

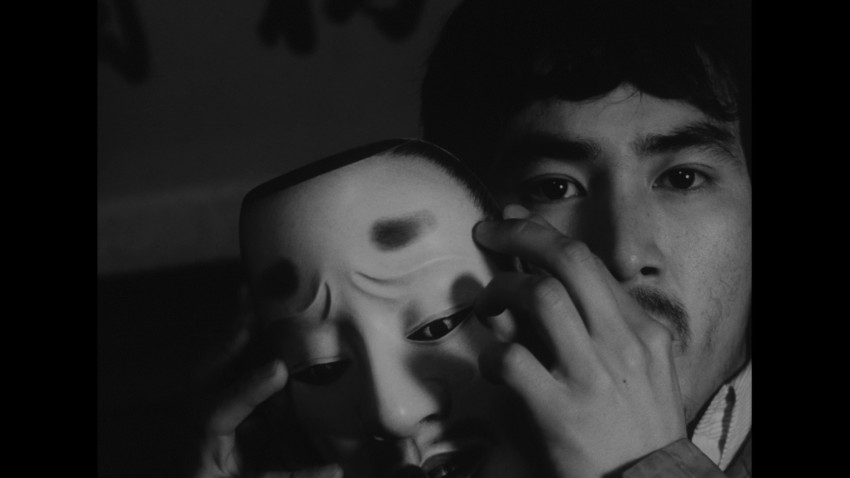

This Transient Life is actually the easiest in the set to describe. Domenig’s later review for Midnight Eye, published in 2004, goes into more detail about its tale of a young man, Masao, obsessed with Buddhist sculptures, who falls for his sister, Yuri, in a big way, much to the chagrin of the young student lodging beneath the roof of the siblings’ parents and a further love rival in the form of a local acolyte priest who also has an eye on her. The film is beautifully shot in striking monochrome and is undeniably sexy, no less so than in the scene of the consummation of the brother and his comely sister’s transgressive passions in which Noh masks play a large role. It is likely that it is this aspect, rather than an interest in any putative Japanese or Buddhist content, that is likely to provide the main lure for viewers of any cultural background.

Ditto Mandala, the intent of which is less clear. It is described by Anton Bitel’s liner essay as “a fragmentary tale of the very different directions taken by two angry young men in their struggle to find, or change, their place in the world… full of jarring symbols, stilted dialogue, unapologetic misogyny and an endless array of alienation effects… a nexus of ideas and associations interweaving religion, politics and anthropology to create an image of empty human strivings.” It is as good a definition as one could hope for a film that expresses sophisticated ideas about time, expectation, contentment and living in a turbulent political moment within a scenario involving a mystic sex cult that espouses rape as an act of revolution.

Mandala is the only of the trilogy shot in colour, making atmospheric use of a raw-grained film stock with a colour palette of cool blues and deep greens. It looks absolutely startling, but for me the poetic treatment of the repeated sexual assaults on the beach, rather than rendering them as the acts of violence that they undeniably are, reminded me very much of the work of Koji Wakamatsu from the 1960s and early 1970s, such as Chronicles of an Affair (1965) or Running in Madness, Dying in Love (1969): that is to say, films that have aspirations to make philosophical, social and political statements within the expectations of the eroduction sexploitation genre, and thus are helplessly hamstrung by the sexual politics of a bygone age.

Mandala is the only of the trilogy shot in colour, making atmospheric use of a raw-grained film stock with a colour palette of cool blues and deep greens. It looks absolutely startling, but for me the poetic treatment of the repeated sexual assaults on the beach, rather than rendering them as the acts of violence that they undeniably are, reminded me very much of the work of Koji Wakamatsu from the 1960s and early 1970s, such as Chronicles of an Affair (1965) or Running in Madness, Dying in Love (1969): that is to say, films that have aspirations to make philosophical, social and political statements within the expectations of the eroduction sexploitation genre, and thus are helplessly hamstrung by the sexual politics of a bygone age.

One might tenuously argue that rape is being used symbolically rather than as spectacle here, but even if we make the distinction between the act and representations of the act, the centrality of rape as a narrative conceit within the film essentially boils down to male filmmakers using women’s bodies to make a point about power relations and morality. As Bitel rightly points out, ‘most of today’s viewers will struggle to separate this unpalatable part of the film from its political, philosophical and theological content. Rape sullies everything here, and adds, in a not entirely welcome way, to the challenges of viewing’.

Bitel’s essay is a wonderful example of the importance of being cognisant of the pitfalls inherent in picking apart the complexities of these films – and they are indeed complex films. Attempts by non-Buddhists trying to isolate the Buddhist aspects of the trilogy run the danger of sounding like the writer in question has just ransacked a library, and is culturally distancing themself from their less palatable elements.

With incest and rape now ticked off the list, Poem proves the least contentious of the three in terms of content, but by far the most opaque in terms of intent. If Mandala’s blend of Wakamatsu-meets-Robbe-Grillet at least followed some sort of narrative logic before spiralling out into complete esoteric weirdness, then Poem (presented in its 120-minute theatrical cut and a 137-minute extended version) is even more cryptic in its portrait of Jun, a houseboy who absorbs himself in the art of calligraphy in his downtime between patrolling the household, flashlight in hand, where two scheming brothers dwell.

Poem is perhaps the purest distillation of Jissoji’s vision in the trilogy, and Espen Bale’s essay does a good job of exploring the bearings of Zen aesthetics on its cinematic form. For much of the runtime there’s no clear idea as to where the film is going or what, indeed, it is really about. Nevertheless, the camera’s positioning and movements express a worldview where the ephemerality and meaningless of existence are key to the meaning, where characters behave, act and interact completely independently of any human perspectival anchor or moral evaluation. It is quite fascinating.

The other extras in the package – two essays by Tom Mes and the characteristically vivacious audio introductions and scene-specific commentaries of David Desser, author of the first English-language book on the Japanese New Wave, Eros Plus Massacre (1988) – are less focussed on the meanings of the films than their context within the director’s own career, Japanese cinema history, and specifically within the output of ATG.

(I should add here there is no contextual exegesis at all for It Was a Faint Dream, a haunting Tale of Genji-esque portrait of life, death, and scandalous passion within the cloistered confines of Imperial Court in 13th century Kyoto. Also filmed in colour, Jissoji’s fourth and final work for ATG is beautifully shot, and seemingly more straightforward than the other the films, and to me perhaps the most intriguing. A real treat.)

Just to end this review with a bit of context, ATG was originally formed with the intention of introducing high-quality foreign art cinema to Japan, as well as providing exhibition possibilities for independent directors such as Hiroshi Teshigahara, Kaneto Shindo and Susumu Hani in Japan. It began providing production financing for Japanese films in 1967 with Shohei Imamura’s A Man Vanishes, and is perhaps best known for funding the more artistically ambitious and challenging works of Nagisa Oshima, including Death by Hanging (1968) and Diary of a Shinjuku Thief (1969).

Just to end this review with a bit of context, ATG was originally formed with the intention of introducing high-quality foreign art cinema to Japan, as well as providing exhibition possibilities for independent directors such as Hiroshi Teshigahara, Kaneto Shindo and Susumu Hani in Japan. It began providing production financing for Japanese films in 1967 with Shohei Imamura’s A Man Vanishes, and is perhaps best known for funding the more artistically ambitious and challenging works of Nagisa Oshima, including Death by Hanging (1968) and Diary of a Shinjuku Thief (1969).

Two things worth pointing out at this juncture is that as well as providing filmmaking opportunities for directors such as Oshima who had left the commercial studio system, it also gave directors from outside the film industry the chance to make their first features. Jissoji’s connection to ATG came via Oshima who, always with one eye on popular culture, was impressed enough by the younger television director’s work on Ultraman to give him the opportunity to direct the 30-minute short When Twilight Draws Near (1969). As Jissoji’s first work for ATG and his first feature-length film, This Transient Life represents ATG’s role in fostering the first generation of Japanese filmmakers who cut their teeth in television before making their debuts. It is prime early example of the rupture with Japanese cinema’s studio era.

The second point of interest, which seldom gets emphasised, is the way in which ATG positioned the whole concept of what constituted art cinema in Japan within a well-established European canon of directors such as Bergman, Buñuel, Cocteau and Cassavetes. Save for rare examples like Satyajit Ray who had already found favour in Europe, there were no Asian films or filmmakers represented within ATG’s release roster, as the company promoted its output within a predominantly Eurocentric auteurist framework, in which its Asian neighbours might as well not have existed.

This much is evident from Arrow’s previous boxset release from 2015, Kiju Yoshida: Love + Anarchism, with Kiju Yoshida’s work for ATG often described as bearing a stylistic kinship with Michelangelo Antonioni. Jissoji’s ATG films represented here certainly fit such auteurist discussions, although it is more difficult to think of a foreign counterpart (some have suggested Carl Dreyer or Robert Bresson, although these two of course never directed kids superhero movies). With running times of over the two-hour standard, the films are all arguably longer than they need to be, but don’t suffer unduly through their lengths, and share a visual style that is highly individualistic and inextricably linked with their director’s vision.

Or are they? A whole monograph could be written about Jissoji and his work, and Arrow’s release of The Buddhist Trilogy at least makes this more of a possibility than it ever was before. However, as I have already strained the conventional word-count for a review of this nature [A little bit – Ed.], I’ll conclude by observing that much as we could argue that these films represent an aspect of his career quite distinct from his Ultraman adventures and the erotic-grotesque-nonsense of his Rampo adaptations, all but one of the films bear the visual hallmarks lent by the cinematographer with whom Jissoji would work for virtually all of his career, Masao Nakabori. The only exception is Mandala, shot by Yuzo Inagaki (although he is also credited alongside Nakabori and a third cinematographer, Kazumi Oneda, as sharing camera duties on This Transient Life).

A not inconsiderable degree of Jissoji’s remarkable stylistic consistency must be attributed to Nakabori’s stunning approach to the visuals, with a masterful use of natural light and compositions that often confine the action and details within little windows that comprise a small part of a much larger span of the screen; the characters, for example, are often crammed into the top quarter while the rest of the image is devoted to the textures of the floor or other internal architectural features, or sometimes plunged into complete darkness. Most strikingly in It Was a Faint Dream, large areas of the screen are obscured by blurry filters or prismatic sprays of colour.

Interestingly, while Inagaki’s main cinema credits of any significance beyond Mandala are for the 1972 kaiju film Daigoro vs. Goliath (1972), the big-screen celebration of perky popsters Mie and Kei in Pink Lady’s Motion Picture (1978), the most notable deployment of Nakabori’s unique approach to the camera comes in another much later example of art-house auteurism, which is Hirokazu Kore’eda’s Maborosi (1995), which by some strange cosmic collision of fate, has also makes its UK Bluray debut this August.

Nakabori’s contribution to Jissoji’s vision certainly means that even if one doesn’t catch all of the meaning of these remarkable yet admittedly challenging films, they scream out to be re-watched, contemplated and savoured. Some might debate the extent to which the director himself might be considered a forgotten or neglected genius, but on the evidence presented here, his was certainly a singular and potent vision that deserves further consideration than it has been afforded so far. The biggest shame is it never happened in Jissoji’s lifetime.

Akio Jissoji’s Buddhist Trilogy, in… er… four parts, is released on Blu-ray by Arrow.

Jean Williams

September 3, 2019 1:02 pm

Although the Arrow set is decent, the fact it failed to mention the inclusion of the fourth film anywhere on the packaging, nor how it's linked to the other three/four in the "Buddhist Trilogy" series, and simultaneously fails to explain why there are two versions of "Poem"; what the differences are between the two edits, nor if one is the preferred version over the other, this year-long delay is a bit laughable to be honest. It feels like a rushed job. The picture is reasonable, but there is still issues with some scenes being dark, undetailed and/or not as decent looking (for a Hi-Definition Blu-Ray) as they should be. Overall, it's not one of their best editions - no matter how great it may be to see these rarities. Definitely a case of "Must do better next time".