Books: Anime Fan Communities

March 16, 2016 · 0 comments

Andrew Osmond on a study of transcultural flows and frictions

Animation travels. It’s good at it, often better than live-action. Animation is amenable to dubbing and localising, and its foreign origins often go unnoticed, at least by child viewers. Perfect Blue director Satoshi Kon put it simply. When he was growing up in Hokkaido, “I loved animation, all of it, whether it was Japanese or whether it came from overseas.”

Animation travels. It’s good at it, often better than live-action. Animation is amenable to dubbing and localising, and its foreign origins often go unnoticed, at least by child viewers. Perfect Blue director Satoshi Kon put it simply. When he was growing up in Hokkaido, “I loved animation, all of it, whether it was Japanese or whether it came from overseas.”

Such pliable mobility has consequences. For starters, cartoons can mutate considerably from one country to another. A famous example is Britain’s beloved The Magic Roundabout, which was very different from the French original, Le Manege Enchante, because of the changed scripts and characters. There can be backlashes against imported animation, especially concerning its impact on children. In France, there was an outcry in the 1980s at the anime imports in kids’ TV slots, such as Fist of the North Star (or Ken le survivant). More recently in Britain, a polemical film called for “British programmes for British kids,” using animation from another nostalgic institution, The Wombles. You can see the film here; and yes, that’s Bernard Cribbins, voice of the Wombles, on the soundtrack.

Sandra Annett’s book is called Anime Fan Communities: Transcultural Flows and Frictions. Fan communities are less the subject of the book than its destination – the phenomenon of Japanese animation gaining fervent fans in far-off places and cultures, like Britain and America. The book is a half-and-half split, with the first hundred pages looking at the early history of world animation. Some of the discussion deals with cartoon viewers, including the kids who avidly love, say, The Jetsons, but these chapters aren’t about fandom as most people understand it. It’s the book’s second half that takes some observations from the first and applies them to case studies from animation (largely anime) fandom.

Throughout the book, examples are paired up in the argument as mirror images. Annett starts by looking at the animation movements between Japan and America in the years before World War II. On the one hand, she examines an American Betty Boop cartoon by the Fleischer studio, specifically aimed at Japanese viewers, called “A Language All My Own”. She then sets this against a Japanese cartoon called “Tengu Taiji” which features, Annett claims, an unofficial Betty Boop clone. Moving on to World War II animation, Annett considers Disney cartoons aimed at South America, and Japanese cartoons about liberating Asia, and how each side wooed the ‘ethnic’ peoples cartooned on screen.

Throughout the book, examples are paired up in the argument as mirror images. Annett starts by looking at the animation movements between Japan and America in the years before World War II. On the one hand, she examines an American Betty Boop cartoon by the Fleischer studio, specifically aimed at Japanese viewers, called “A Language All My Own”. She then sets this against a Japanese cartoon called “Tengu Taiji” which features, Annett claims, an unofficial Betty Boop clone. Moving on to World War II animation, Annett considers Disney cartoons aimed at South America, and Japanese cartoons about liberating Asia, and how each side wooed the ‘ethnic’ peoples cartooned on screen.

Later chapters compare the way television is reflexively portrayed in TV cartoons, looking at two contrasting sci-fi cartoons: America’s The Jetsons (the 1963 series) and Japan’s Cowboy Bebop. In The Jetsons, TV creates corporate consumer addicts; in Cowboy Bebop, it reflects the lonely, separated audiences of postnationalism gone sour. Annett, borrowing a phrase from globalisation theorist John Tomlinson, describes this state as a “plurality of isolations.”

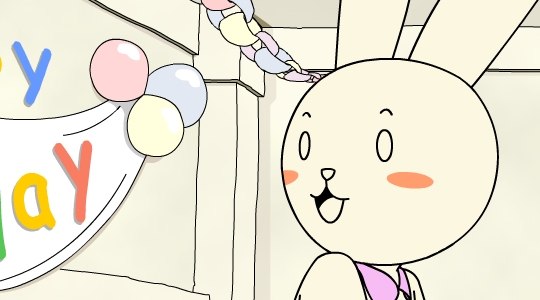

The last big pairing, over sixty pages, is between two recent online fandoms; for a South Korean web toon, “There She Is!!!” (first episode here), about the star-crossed love between a cat and a rabbit, and for the better-known Japanese franchise Hetalia. Both series, despite their disarming cuteness, have provoked some politicised arguments, relating to South Korea’s identity and history. (Anyone with a passing knowledge of Japan’s colonisation of Korea in the last century may guess why the cute spoofing of history by a Japanese artist could make people angry.)

The last big pairing, over sixty pages, is between two recent online fandoms; for a South Korean web toon, “There She Is!!!” (first episode here), about the star-crossed love between a cat and a rabbit, and for the better-known Japanese franchise Hetalia. Both series, despite their disarming cuteness, have provoked some politicised arguments, relating to South Korea’s identity and history. (Anyone with a passing knowledge of Japan’s colonisation of Korea in the last century may guess why the cute spoofing of history by a Japanese artist could make people angry.)

At this point, I think I must slip into the first person. On the one hand, this book is not ‘for’ me; it’s a heavily academic text, assuming knowledge of a theoretical literature I haven’t studied and know nothing of. The first line of the introduction reads, “Friction, as Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing reminds us in her 2005 ethnography of global connections, is not just about slowing things down.” For the outsider, this is as unwelcoming as a book which starts, “We Americans.”

However, unlike some academic texts I’ve tackled, I found I could generally stay afloat, which testifies to Annett’s admirably lucid prose. Moreover, I found the book very interesting, enlightening in its insights and extremely useful, given my own interest in anime as a part of world animation. I was especially pleased Annett thinks it’s worthwhile to compare anime with Disney. For more than a decade, many writers on anime have only mentioned the Disney tradition as the playground to be outgrown or the straitjacket to be broken. Or, for more left-leaning commentators, as the corporate-sexist-imperialist dragon to be slain.

Annett is plainly an expert on both world animation and anime. My only ‘factual’ nitpick is the way she seems, perhaps unintentionally, to conflate TV animation, particularly in its early years, and ‘limited’ animation. She writes that many commentators dismiss “the limited animation of TV cartoons as commercialised rubbish,” as if TV animation was disliked by critics because it was limited. In fact, there are many acclaimed cinema cartoons – for example, “The Dover Boys,” “Gerald McBoing Boing”, “The Dot and the Line”, Richard Williams’ “The Little Island” and Bob Godfrey’s “DIY Cartoon Kit” – which are celebrated specifically for their use of limited animation. It may be that critics of a certain generation have a narrow view of what limited animation can do, but to suggest they’re blind to it is untrue.

Annett is plainly an expert on both world animation and anime. My only ‘factual’ nitpick is the way she seems, perhaps unintentionally, to conflate TV animation, particularly in its early years, and ‘limited’ animation. She writes that many commentators dismiss “the limited animation of TV cartoons as commercialised rubbish,” as if TV animation was disliked by critics because it was limited. In fact, there are many acclaimed cinema cartoons – for example, “The Dover Boys,” “Gerald McBoing Boing”, “The Dot and the Line”, Richard Williams’ “The Little Island” and Bob Godfrey’s “DIY Cartoon Kit” – which are celebrated specifically for their use of limited animation. It may be that critics of a certain generation have a narrow view of what limited animation can do, but to suggest they’re blind to it is untrue.

Beyond that, my disagreements should be taken as less criticisms than a sign that the book is doing its job of engaging the reader. I’m not convinced, for example, that the Betty Boop-ish figure in the Japanese film “Tengu Taiji,” mentioned above, is really meant to be Betty Boop. Annett claims that the implicit joke is to have Betty no longer performing “alluring Orientalist femininity, but a parodic martial masculinity asserted in overblown heroic gestures.” For me, that’s like saying Tezuka’s Astro Boy is really supposed to be Mickey Mouse in a robot suit. There’s a resemblance and a real influence, but that’s not the same as a parody. But readers can judge the cartoon for themselves; the Boop-ish character appears three minutes in.

I’m also unconvinced by some of Annett’s arguments about the “ethnic cute” cartoon figure which recurs through the book (predictably, it looms large in the Hetalia discussion). The idea is introduced through the early Disney cartoon, “Little Hiawatha”, a Disneyfication of the life of Native Americans. For Annett, the film’s “colonial discourses” are revealed through Hiawatha’s child appearance and his eventual befriending of animals, which infantilise and animalise him. But how much is this colonial discourse, and how much a reflection of Disney’s already established conventions of cartooning and storytelling? For me, a more interesting question is why classic Disney films draw minority and foreign characters as (cutesy) humans, while their white American characters are animals – Mickey, Donald and Goofy.

I’m also unconvinced by some of Annett’s arguments about the “ethnic cute” cartoon figure which recurs through the book (predictably, it looms large in the Hetalia discussion). The idea is introduced through the early Disney cartoon, “Little Hiawatha”, a Disneyfication of the life of Native Americans. For Annett, the film’s “colonial discourses” are revealed through Hiawatha’s child appearance and his eventual befriending of animals, which infantilise and animalise him. But how much is this colonial discourse, and how much a reflection of Disney’s already established conventions of cartooning and storytelling? For me, a more interesting question is why classic Disney films draw minority and foreign characters as (cutesy) humans, while their white American characters are animals – Mickey, Donald and Goofy.

Perhaps this connects to a remark of Mamoru Oshii (Ghost in the Shell) in a different part of the book, where he says provocatively, “Japanese animators and cartoonists unconsciously choose not to draw ‘realistic’ Japanese characters if they wish to draw attractive characters.” If linking Disney and Oshii seems a bit of a stretch, the whole book encourages such leaps, though there are limits. The last chapter of Anime Fan Communities is presented as an “analysis” of the crazy dream parade scenes in Satoshi Kon’s film Paprika. Annett may be being tongue-in-cheek, but her analysis – which purports to map Paprika’s parade onto the argument presented through the book – had me shaking my head in admiration. It also had me thinking of Room 237, the wonderful documentary about fans of Kubrick’s The Shining and the outer limits of criticism.

Annett’s tone tends to assume agreement, and that the reader recognises certain things as self-evident; for example, the limitations of a nationalist worldview, and the need to supercede it. There’s a startling moment (the start of Chapter 2) where she describes the “unadulterated jingoism” of a Disney propaganda cartoon. It appears from the text that it’s jingoistic because it shows Donald Duck being grateful that he’s living in 1943 America, rather than in 1943 Germany. This seems to be taking cultural relativism to terrifying extremes – though a glance at the actual cartoon (called “Der Fuhrer’s Face”) does more to justify Annett’s description. Hint: look at Donald’s pyjamas in the last scene, or rather try not looking at them.

If Annett finds nationalism bad, she seems equally clear on the good to be found in transculturalism. Towards the end, she writes of the duty of reflective fans, to “confront their complicities in the gendered, ethnic and economic forms of inequality that make up media culture.” She writes with apparent approval of the fan practice of “calling out” (for discriminatory or oppressive behaviour) and of anti-oppression generally. But I wish – and I call myself out on my own biases – that she would occasionally acknowledge the ‘frictions’ between, say, progressive identity politics and other values, such as free speech and expression. As luck (and a quick google) would have it, there’s a recent cartoon-related case which exemplifies such frictions. Perhaps Annett could discuss it in her next book.

Andrew Osmond is the author of 100 Animated Feature Films.

Leave a Reply