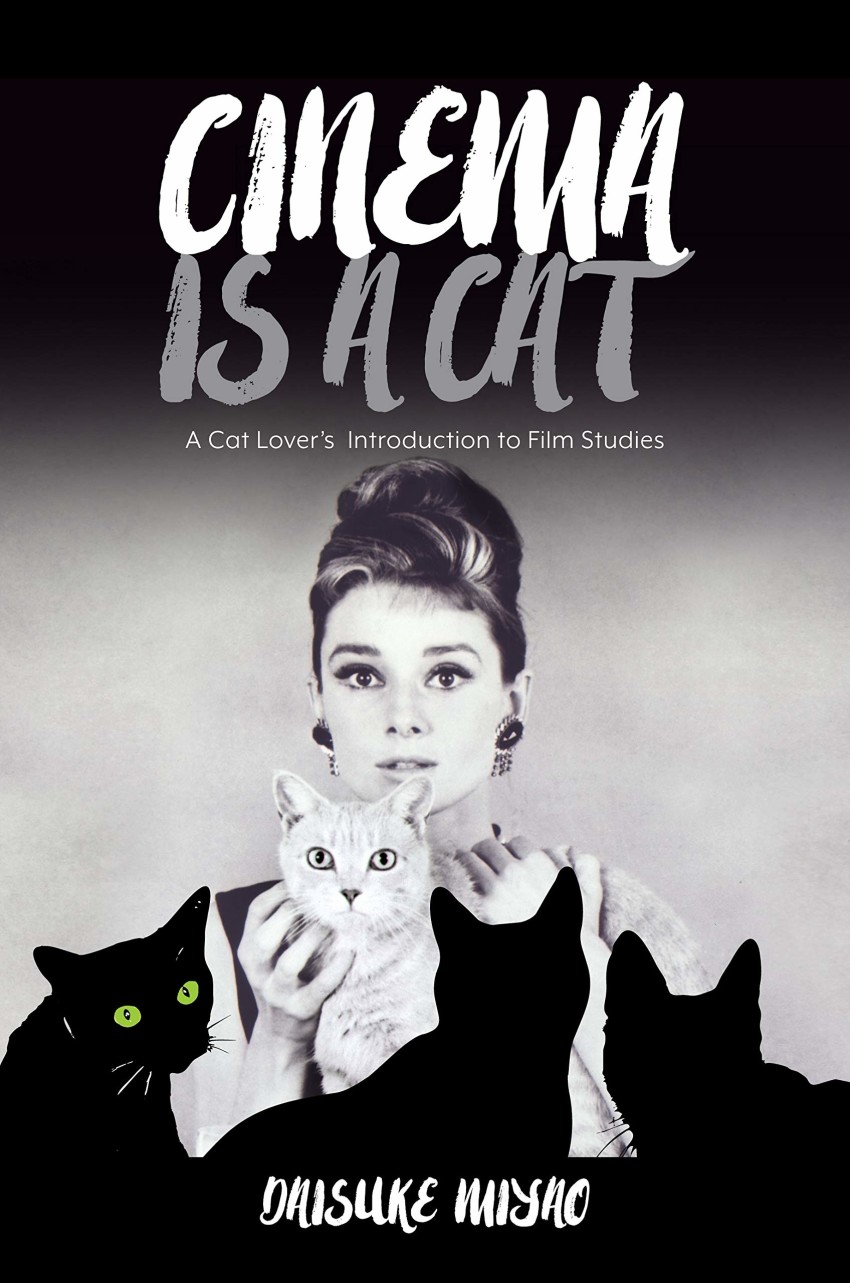

Books: Cinema is a Cat

April 1, 2020 · 0 comments

By Jasper Sharp.

Cinema is a Cat: A Cat-Lover’s Introduction to Film Studies, as its subtitle highlights, is less a scholarly survey of cats in the movies than a cat-led guide as to how to conduct cinematic analysis. Yes, you read that right. This is a book that casts a curious cat’s eye across a variety of titles in which felines play a part, in order to introduce such key areas in film studies as aesthetics, authorship, race, gender, genre and historical specificity.

Cinema is a Cat: A Cat-Lover’s Introduction to Film Studies, as its subtitle highlights, is less a scholarly survey of cats in the movies than a cat-led guide as to how to conduct cinematic analysis. Yes, you read that right. This is a book that casts a curious cat’s eye across a variety of titles in which felines play a part, in order to introduce such key areas in film studies as aesthetics, authorship, race, gender, genre and historical specificity.

Despite the pedigree of its author, Daisuke Miyao, less than half of the focus is on Japanese works. The first four of the nine (of course!) individual chapters look at Classic Hollywood titles, including Josef von Sternberg and Marlene Dietrich’s first American collaboration Dishonored (1931), and Alfred Hitchcock’s To Catch a Thief (1955).

This cues up the second part in which the gaze moves eastward across two little-discussed Japanese live-action titles, Shozo, a Cat and Two Women (1956) from the industry’s Golden Age heyday and the more recent Samurai Cat (2014), as well as a sole anime title in the form of the 1997 feature Jungle Emperor Leo, and one South Korean film Take Care of My Cat (2001). In the epilogue, Miyao considers The Cats of Mirikitani (2006), a documentary about an aged cat-loving street artist who was one of the thousands of American-Japanese civilians caged up in U.S. internment camps during World War 2.

Miyao attributes the motivation for this approach to film theory to a rescue cat named Dica, adopted by his future partner whom he came to know when he first moved from Japan to New York to study film in the mid-1990s. It was through Dica that Miyao first noted an affinity between cats and film, with both characterised by an essence that he sees as elusive, undefinable and “phantomlike.” When Dica died in 2008, Miyao was prompted to reflect upon his relationship with cinema and his feline muse. The first Japanese-language version of this book appeared in 2011.

Miyao attributes the motivation for this approach to film theory to a rescue cat named Dica, adopted by his future partner whom he came to know when he first moved from Japan to New York to study film in the mid-1990s. It was through Dica that Miyao first noted an affinity between cats and film, with both characterised by an essence that he sees as elusive, undefinable and “phantomlike.” When Dica died in 2008, Miyao was prompted to reflect upon his relationship with cinema and his feline muse. The first Japanese-language version of this book appeared in 2011.

Miyao’s notable English-language publications – Sessue Hayakawa: Silent Cinema and Transnational Stardom (2007), about Hollywood’ first major Asian star of the silver screen, and The Aesthetics of Shadow: Lighting and Japanese Cinema (2013) – come highly recommended for their informativeness and clarity of writing and for bringing a fresh perspective on such areas of star formation and film technology on the development of national and transnational film cultures. Elements of both of these studies find their way into this substantially reworked and expanded English-language edition of Cinema is a Cat.

It might seem an eccentric prospect, but Miyao’s strategy of using feline characteristics (such as “cats like dark or small spaces”, or “cats are always moving”) to discuss the history, methodologies and terminologies of film studies works surprisingly well in providing an accessible entry to the subject that can also be recommended to a non-academic readership. After all, academia is rife with scholars attempting to force certain films into specific conceptual frameworks like a toddler trying to cram round pegs into square holes. Why shouldn’t a cat-led approach to film analysis be any less valid or viable than the critical apparatus of Saussure, Deleuze or Lacan? Cat-centric language and observations based on their innate behaviour is considerably more familiar to ordinary mortals, after all, and as Miyao points out, cats have been an omnipresent part of moving-image culture from at least as far back as the 30-second short The Boxing Cats, produced in 1894 for Thomas Edison’s Kinetoscope device. One barely needs to mention the prevalence of cat memes and videos on YouTube or other social media platforms.

The opening chapter on Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961) to introduce the importance of composition and colour in articulating the film’s characters and their plights should allay fears about the approach. Miyao draws attention to the way director Blake Edwards’ frames the character of Holly Golightly, played by Audrey Hepburn, throughout the film as if she were a cat: she stays out all night and sleeps all day; she regularly pesters the landlord of her apartment block, Mr Yuniyoshi (in a notorious racially insensitive turn by Mickey Rooney), to let her in after coming home without her key; and there is her continuous upwards and downwards movement, whether climbing through windows to use the emergency fire escape or leaping on to her kitchen counter to reach a bottle on the top of a cupboard.

Cynics might initially see such analogies as stretching things a bit, and perhaps even pointless. The fact Holly’s former husband is a veterinarian might be seen as a red herring, especially when one considers his specialism is in horses. Miyao goes on, however, to draw attention to the ways in which Holly shares her living space with her own cat, paying close attention to their interactions and matching behaviours within the same frame. They drink milk from the same bottle from the fridge, and at one point we also see her drinking an identically coloured White Russian cocktail from a Martini glass. In various scenes, Holly also climbs on men’s shoulders, seemingly just as often as her cat does.

Cynics might initially see such analogies as stretching things a bit, and perhaps even pointless. The fact Holly’s former husband is a veterinarian might be seen as a red herring, especially when one considers his specialism is in horses. Miyao goes on, however, to draw attention to the ways in which Holly shares her living space with her own cat, paying close attention to their interactions and matching behaviours within the same frame. They drink milk from the same bottle from the fridge, and at one point we also see her drinking an identically coloured White Russian cocktail from a Martini glass. In various scenes, Holly also climbs on men’s shoulders, seemingly just as often as her cat does.

There is a crucial idea underpinning all of these observations in a film about a high-class call-girl and her author love-interest Paul, another “kept man”, produced in an era when new ideas about morality, sexual liberation and female emancipation were percolating beneath the censorship restrictions of the Hollywood production code (all these aspects were present in Truman Capote’s source novel of course). That is the idea of confinement. While Holly is portrayed as free and independent, she occupies a social environment dominated by men upon whom she ultimately relies for this freedom. Miyao provides numerous examples as to how this confinement is articulated visually through Holly’s positioning, like the cat who shares the same domestic space with her, within small square frames or darkened areas within the larger widescreen image.

Breakfast at Tiffany’s focus on framing segues into a discussion of lighting in Jacques Tourneur’s Cat People (1942), which also draws attention to other social and historical aspects such as the way the narrative attempts to “tame” the foreign cat woman as an American subject at a time of war, when ideas of nationhood were paramount. To Catch a Thief (1955) looks at editing, progressing from the basic equation between chase, action and narrative to introduce more sophisticated ideas about point-of-view shots and Laura Mulvey’s theories of the gendered gaze, again using the cat as an entry into the discussion (they “never stop watching and are always conscious of being watched”).

Miyao’s overview of the various topics of interest within film studies swerves into more sophisticated areas as it moves to its Asian examples. His discussion of Shozo, a Cat and Two Women (1956), directed by Shiro Toyoda, shows the pitfalls of applying a Western academic discipline, which has evolved with its roots firmly planted in its own cultural products, to those of another industry with its own traditions and practices. This little-seen drama is considered in the light of the work of the author from whom it was adapted, Junichiro Tanizaki, and his changing relationship to cinema and Western culture in the early decades of the twentieth century; the rivalry and respective career crises of its two main female stars, Isuzu Yamada and Takako Irie, both considered at the top of their game in the 1930s; the focus in the film on these aging actress’s physicality and corporeality in a post-war era when Japanese women were being presented in a very different fashion; and the lingering shadow of the homegrown ‘ghost cat’ genre with which both had become associated. A film that might be seen by foreign viewers coming at it cold as a straightforward literary adaptation thereby takes on the patina of something darker and more complex, in a similar vein to What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? , while the idea of genre purity is questioned, framed as something constantly changing and open to hybridisation. A bit like a cat breed, in fact.

The chapter on Jungle Emperor Leo (1997) also looks at the cultural and industrial factors that have shaped the aesthetic of the anime industry, which the film stands as a representative of, by way of comparison to a much more famous American counterpart, The Lion King (1994). The Disney film was accused by certain anime fans back in the day of seeming that little bit too close for comfort to Kimba, the White Lion, the Tezuka manga and animated TV adaptation, which ran up until 1966 and aired around this same time on US television. In turn, the subsequently-produced Jungle Emperor Leo feature, though officially based on this manga source material, curiously deviated from Tezuka’s original narrative in a number of regards to bring it closer towards the coming-of-age template of the more recent Disney hit.

The chapter on Jungle Emperor Leo (1997) also looks at the cultural and industrial factors that have shaped the aesthetic of the anime industry, which the film stands as a representative of, by way of comparison to a much more famous American counterpart, The Lion King (1994). The Disney film was accused by certain anime fans back in the day of seeming that little bit too close for comfort to Kimba, the White Lion, the Tezuka manga and animated TV adaptation, which ran up until 1966 and aired around this same time on US television. In turn, the subsequently-produced Jungle Emperor Leo feature, though officially based on this manga source material, curiously deviated from Tezuka’s original narrative in a number of regards to bring it closer towards the coming-of-age template of the more recent Disney hit.

Miyao outlines a simple history of a Japanese animation industry that has always been in dialogue with the larger and more established American one, arguing that Toei Animation was established in the 1950s as a conscious rival to Disney, with its eyes also on international markets, rather than an isolated alternative. He goes on to interrogate the history of Western linear perspective in Japan, the ‘Superflat’ aesthetic spearheaded by Takashi Murakami in the 2000s, and the Studio Ghibli luminary Isao Takahata’s claims (rather daft, in my opinion) that manga and anime’s antecedents can be traced back to twelfth-century illustrated handscrolls known as giga in order to raise questions as to how “Japanese” Japanese animation really is.

Tezuka’s limited animation style is likened to the Hokusai Manga (1814-78), the series of sketchbooks that, curiously enough, features a preponderance of cats amongst the other depicted creatures. Miyao proposes that Tezuka, following Hokusai, attempted to create still images that individually capture movement rather than create the illusion of movement through the succession of realistic still images. Tezuka’s work “inevitably created awareness of how movements are created in animation” and “Like the work of Impressionist painters… challenged the supremacy of photographic realism.”

One might find one’s brows furrowing in dissent at some of these points. Takahata and Tezuka both cut their teeth at Toei Animation in the 1950s, so both would have been in a position to realise the strong bearing of budgetary constraints rather than artistic heritage in the evolution of the anime style. Miyao’s mention of the influence of Japanese artists on the French Impressionists in the 19th century does however flag up a forthcoming publication by the author scheduled for August 2020 and entitled Japonisme and the Birth of Cinema, and suddenly the central argument comes into focus. Whether there is something intrinsically Japanese about anime can be debated till the cats come home. What is not debatable is the way that anime is currently one of the country’s most visible cultural exports and has adopted a central role in the “Cool Japan” promotional project.

Which leads us to the final chapter on Samurai Cat (2014), a silly and not particularly well-known live-action film that did the festival circuit a few years back. The film is of interest to Miyao in providing an example of a genre, the chanbara samurai film, specific to this particular national industry. The genre’s formulation also is used to show how the Japanese film industry adopted a strategy of self-exoticism and self-orientalisation in the immediate post-war era of the 1950s when the likes of Rashomon and Seven Samurai first gained traction in the West, with filmmakers exaggerating or over-playing those cultural or aesthetic elements that were different from American or European films – much like anime in the 21st century, in fact.

Cinema is a Cat is a clear and concise read that lays out its agenda in a sprightly and unashamedly playful fashion, signposting a lot of areas for further exploration while never getting unduly bogged down in the nitty-gritty. The terminology and theoretical concepts should be familiar enough to those already ensconced within the academic world, although this won’t hamper any enjoyment of Miyao’s idiosyncratic approach in applying them. For those curious outsiders to university film departments, however, it feels like being let in through the cat flap into a domain of seemingly impenetrable jargon and ideas.

Jasper Sharp is the author of The Historical Dictionary of Japanese Cinema. Cinema is a Cat: A Cat Lover’s Introduction to Film Studies is published by the University of Hawaii Press.

Leave a Reply