Books: Harryhausen’s Lost Movies

February 2, 2020 · 0 comments

by Jeremy Clarke.

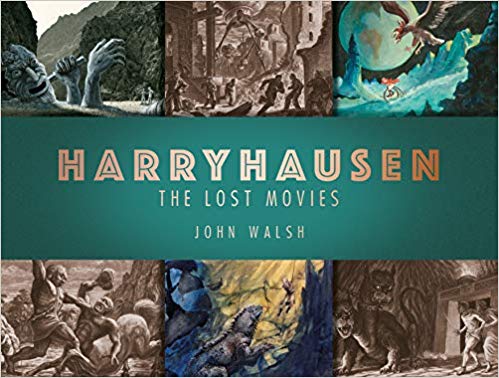

There’s nothing else quite like the filmography of stop-frame animator and special effects maestro Ray Harryhausen (1920-2013). A new book, Harryhausen: The Lost Movies, is an undeniable treasure trove for those familiar with his films, which include such gems as Jason and the Argonauts and One Million Years B.C. and incorporate fantastical, stop-frame animated creatures and additional bravura special effects into live-action movie narratives.

There’s nothing else quite like the filmography of stop-frame animator and special effects maestro Ray Harryhausen (1920-2013). A new book, Harryhausen: The Lost Movies, is an undeniable treasure trove for those familiar with his films, which include such gems as Jason and the Argonauts and One Million Years B.C. and incorporate fantastical, stop-frame animated creatures and additional bravura special effects into live-action movie narratives.

Compiled by documentary film maker and author John Walsh from over 50,000 items in the Ray and Diana Harryhausen Foundation archive, this coffee-table book sets out to provide an overview of the film maker’s oeuvre through his various unmade projects, lavishly illustrated with photographs and drawings.

In several short introductions, heavyweight film directors Guillermo del Toro, John Landis and John Boorman lament the many unmade projects that seem inevitably to litter a film-maker’s career. Ray Harryhausen was not a director, although many of his films, particularly those initiated with his regular producer Charles Schneer, bear the unmistakable Harryhausen stamp far more than the mark of the directors he and Schneer hired to work on them.

In several short introductions, heavyweight film directors Guillermo del Toro, John Landis and John Boorman lament the many unmade projects that seem inevitably to litter a film-maker’s career. Ray Harryhausen was not a director, although many of his films, particularly those initiated with his regular producer Charles Schneer, bear the unmistakable Harryhausen stamp far more than the mark of the directors he and Schneer hired to work on them.

Walsh sensibly divides the lost movies into three categories. Unused Ideas – movie ideas that Ray created from a storyline using artwork, sculptures and (in some cases) test footage that never made it to the screen; On the Cutting Room Floor – concepts or scenes cut from or unrealised in movies he actually made; Turned Down By Ray – films he was offered but refused.

This might lead you to expect the book to be divided accordingly into three sections. However it instead follows the well-worn template of going through someone’s filmography in chronological order. The first chapter contains a number of unmade films by Harryhausen’s mentor Willis O’Brien (1886-1962), the special-effects genius behind the 1933 King Kong. When Ray first met him in 1939, O’Brien was working on War Eagles, set largely in a lost valley where Vikings ride giant eagles to repel a rampaging allosaurus herd. Harryhausen always wanted to make his own version after the original production got cancelled (its most prominent modern vestige is a novelisation, written by none other than Robotech’s Carl Macek).

An early inspiration came in the form of three illustrations for O’Brien’s unmade, pre-Kong outing Creation, which Ray found in an art store in Los Angeles where he grew up. The image of a pterodactyl flying off with a woman in its claws would later inspire scenes in One Million Years B.C. (1966) and The Valley Of Gwangi (1969). Ray would work with O’Brien on stop-frame gorilla picture Mighty Joe Young (1949), the budget overruns on which put paid to O’Brien’s proposed follow up Valley of the Mist, two pieces of Ray’s artwork for which are lovingly reproduced in the book.

Many films are covered in part of a page or a double-page spread. King Kong, O’Brien’s best known work, which Harryhausen always wanted to remake, gets six pages. RKO were reluctant to part with the rights as they didn’t want another studio to do a remake. Nevertheless, they licensed the property to Japan’s Toho in the sixties for King Kong vs. Godzilla (1962) and King Kong Escapes (1967) and looked set to do a similar deal with Britain’s Hammer Films following the latter’s success with One Million Years B.C. – Harryhausen had relocated from Los Angeles to London in 1960 to take advantage of a superior travelling matte process at Rank Film Labs.

When the Kong rights deal fell through, Hammer opted instead for another dinosaur picture, When Dinosaurs Ruled the Earth (1970) which Harryhausen turned down as he was busy on The Valley of Gwangi. The film benefited from excellent effects and stop-frame work by Jim Danforth, an animator who, like Harryhausen, had worked on George Pal’s Puppetoons series. Danforth’s assistant David Allen made his own version of a couple of scenes from Kong which he eventually reanimated for a highly regarded Volkswagen commercial. Hammer also proposed a One Million sequel called When the Earth Cracked Open, which was never made.

When the Kong rights deal fell through, Hammer opted instead for another dinosaur picture, When Dinosaurs Ruled the Earth (1970) which Harryhausen turned down as he was busy on The Valley of Gwangi. The film benefited from excellent effects and stop-frame work by Jim Danforth, an animator who, like Harryhausen, had worked on George Pal’s Puppetoons series. Danforth’s assistant David Allen made his own version of a couple of scenes from Kong which he eventually reanimated for a highly regarded Volkswagen commercial. Hammer also proposed a One Million sequel called When the Earth Cracked Open, which was never made.

Other projects not to reach the screen include a 1940s version of Dante’s Inferno inspired by the drawings of the great nineteenth century artist and illustrator Gustav Doré (1832-1883), who Ray greatly admired, accompanied in its entry here by an atmospheric Doré image of souls in torment. A decade later, Harryhausen made models and shot test footage for a version of Baron Munchausen, Rudolf Erich Raspe’s collection of stories about a teller of tall tales. This property has been filmed by such fantasy luminaries as French film pioneer Georges Méliès, Czech trick-film maker Karel Zeman and Monty Python animator-turned-film-director Terry Gilliam. Ray built models of the Baron and shot footage of him talking to a giant face, as well as making a number of preproduction paintings.

The two rich seams of the Arabian Nights’ Sinbad stories and Greek mythology led to two series of films. The Sinbad films can be seen as having their roots in Harryhausen’s SF epic 20 Million Miles To Earth (1957) where an early drawing of the gargantuan alien fighting an elephant looks suspiciously like the ever-popular cyclops from The 7th Voyage Of Sinbad (1958), but with two eyes rather than one.

Reading between the lines, Harryhausen and Schneer may have toned down their narratives over the years to keep the censors happy and service a family audience. The Golden Voyage of Sinbad (1973) originally had a much darker opening in which a tiny homunculus pours acid over the face of the sleeping Grand Vizier, scarring him and causing him to wear the golden mask to hide the resultant scars. The homunculus, mask and burned face survived into the film, but the acid attack didn’t. A similar fate befell an intriguing proposed origin sequence in Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger (1977) wherein a magically-powered bronze automaton Minoton is brought to life by several mysterious, mouthless Shadow Men. A further proposed film Sinbad Goes to Mars was never made, but artist Chris Foss, who also worked on both Alien and Jodorowsky’s Dune, produced some breath-taking colour sketches during its preproduction phase.

Reading between the lines, Harryhausen and Schneer may have toned down their narratives over the years to keep the censors happy and service a family audience. The Golden Voyage of Sinbad (1973) originally had a much darker opening in which a tiny homunculus pours acid over the face of the sleeping Grand Vizier, scarring him and causing him to wear the golden mask to hide the resultant scars. The homunculus, mask and burned face survived into the film, but the acid attack didn’t. A similar fate befell an intriguing proposed origin sequence in Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger (1977) wherein a magically-powered bronze automaton Minoton is brought to life by several mysterious, mouthless Shadow Men. A further proposed film Sinbad Goes to Mars was never made, but artist Chris Foss, who also worked on both Alien and Jodorowsky’s Dune, produced some breath-taking colour sketches during its preproduction phase.

Harryhausen wanted to shoot his highly regarded, multiple skeleton fight on Jason and The Argonauts (1963) in twilight but ended up setting it in broad daylight to avoid an X certificate. His final feature Clash of the Titans (1981) had its most memorable scene changed for a very different reason when actor Harry Hamlin, who plays Perseus, insisted on cutting off Medusa’s head with his sword as in the original Greek myth rather than beheading her accidentally with his flying shield as scripted. The subsequent unmade Aeneid adaptation Force of the Trojans attempted a more faithful filmic interpretation of Greek myth and happily is today once again under development under the banner of the newly formed Ray Harryhausen Films Ltd. That’s a more optimistic outcome than the one which befell Harryhausen’s proposed, entirely stop-frame series The Story of Odysseus, which was in development 1996-1998 at Manchester-based animation house Cosgrove Hall before being cancelled.

Harryhausen: The Lost Movies by John Walsh is published by Titan Books.

Leave a Reply