Books: Perfect Blue

September 1, 2018 · 0 comments

By Andrew Osmond.

It’s said that bad books make good films (and vice versa). Perfect Blue makes that case forcibly. Satoshi Kon’s film version is a landmark in animated horror, subjecting a vividly sympathetic protagonist to fiendish mind-games. But the source book is plain bad, descending into infantile guignol that’s less perverted than pre-potty trained. Going from Kon’s film to the book is like going from Psycho to Blood Feast.

It’s said that bad books make good films (and vice versa). Perfect Blue makes that case forcibly. Satoshi Kon’s film version is a landmark in animated horror, subjecting a vividly sympathetic protagonist to fiendish mind-games. But the source book is plain bad, descending into infantile guignol that’s less perverted than pre-potty trained. Going from Kon’s film to the book is like going from Psycho to Blood Feast.

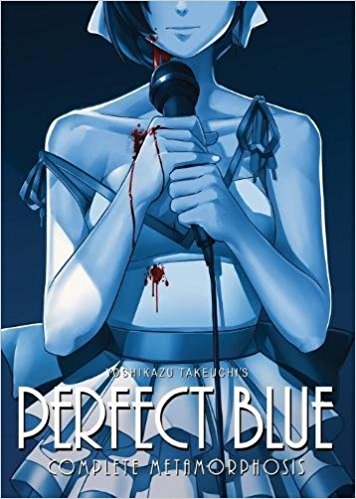

Written by Yoshikazu Takeuchi, the book was originally published in 1991. More than a quarter-century later, it’s now available in English from Seven Seas Entertainment. Its English title is Perfect Blue: Complete Metamorphosis, though its Japanese subtitle, Kanzen Hentai, can also be read as Total Pervert.

In interviews, Kon and his scriptwriter Sadayuki Murai stressed how much they changed the book. Kon never even read it; he was given a script adaptation by its author, Yoshikazu Takeuchi, which the Madhouse studio let Kon and Murai change as they wished. They were only required to use the elements of an idol singer and a stalker, and keep it a horror story. Madhouse was good at selling horror anime abroad; its Wicked City and Doomed Megalopolis were both book adaptations.

The Perfect Blue book is indeed very different from the film. True, the main character is still Mima Kirigoe, a Tokyo-based idol singer with a cutesy persona. As in the film, she’s harassed by a demented fan and stalker who’s outraged that she’s perverting her wholesome image. Certain other elements remain in the film, such as Mima doing a heavily sexualised photo-shoot, and a climactic encounter on a dark studio stage.

But so much else is vastly different. In the book, Mima is a lone singer, not part of a group. She doesn’t act in a TV series called Double Bind, and the book has none of Kon’s edifice of mirrored realities, mixing and collapsing. Mima has no mental breakdowns; she never doubts her identity, sanity or reality. There are no phantom Mimas appearing to her or anyone else. Today, the book reads like a version of Psycho without mother complexes, or a Jekyll and Hyde where the title characters are different people.

In the book, Mima is more angered than scared by the stalker, promising to “beat the living daylights out of him”. She’s not retiring from singing; she’s merely changing her image, because (the book claims) cute idols are being trumped by sexy ones. She has only minor reservations about the racy photoshoot, no trauma or guilt about doing it, and there’s no equivalent to the “pseudo-rape” at the film’s centre. Online harassment isn’t an issue in 1991; her stalker relies on letters and phone calls.

The book’s other characters share names with ones in the film, but that’s about all. Tadokoro, Mima’s manager, and Murano, the photographer, are bland nice guys, while Rumi, Mima’s female assistant, is similarly nondescript, in extreme contrast to the film.

There’s also a woman called Eri, who’s entirely different from her film namesake (the lead actress in Double Bind). In the book, Eri is an idol singer and a paid-up b****, who wants to take Mima down for no convincing reason. Her tactics are even wonkier. She’s so determined to hurt Mima’s reputation that she, er, beds a sleazeball entertainment reporter, unworried that she’s just landed a front-page scoop right in his lap!

There’s also a woman called Eri, who’s entirely different from her film namesake (the lead actress in Double Bind). In the book, Eri is an idol singer and a paid-up b****, who wants to take Mima down for no convincing reason. Her tactics are even wonkier. She’s so determined to hurt Mima’s reputation that she, er, beds a sleazeball entertainment reporter, unworried that she’s just landed a front-page scoop right in his lap!

At least the book’s stalker character has some of the traits of the film’s Me-Mania, though he calls himself “Darling Rose”. (Minor spoilers follow.) In the book, he feels like a Crayola version of a character in Silence of the Lambs. Perfect Blue was published the same year as the film, probably too soon to be influenced by that, but the Thomas Harris novel was already acclaimed. However, there’s another plausible film influence – see below.

The book’s stalker also seems influenced by the real horror of Tsutomu Miyazaki, arrested in 1989, who’d preyed on little girls. In the book’s first chapter, the stalker abducts a preteen girl from a playground. He’s described as having huge numbers of videotapes in his room; this recalls the press reports of Tsutomu Miyazaki hoarding a huge video collection, causing him being dubbed “the Otaku Murderer”.

But in an afterword, Takeuchi stresses that the book’s stalker is a “extreme, twisted” fan, and outs himself as a “pop idol superfan, though not twisted or obsessive, of course.” It seems a deliberate effort to dissociate his story from the bogeyman image of otaku that proliferated in Japan after Tsutomu Miyazaki. It may also be why, early in the story, we learn that Mima and Rumi are anime fans, and Mima collects laserdiscs of Toei and Ghibli films.

As for “idol” culture, Takeuchi himself mentions in his afterword that he listens to Noriko Sakai, who was a teenager when she sang the opening theme to Gunbuster. But we’re told in the book that the idol Eri “sold her sex appeal far more than her cuteness” and that “modern fans were looking for the woman in the idol.” This sits very oddly with developments since 1991. By the time that AKB48 was rising in the 2000s, cuteness and sexiness seemed mutually dependent, entwining with “moe” culture in anime. Even a female group like Perfume, their teens long behind them, still project virginal cuteness today.

On the other hand, the book suggests that even if idols in 1991 were more adult, it was still taboo for them to be seen with a boyfriend. In the course of the story, two women make ridiculously dangerous decisions when the stalker presents them with compromising photographs. More than twenty years later, this issue would define the image of Japanese idols abroad, thanks to the “apology video” featuring Minami Minegishi of AKB48.

These background issues are far more interesting than the story. The writing is bland, even when describing things that are meant to be erotic or appalling. Whereas Kon’s film is shocking, the book’s simply laughable. The stalker refers to one of his victims as a guinea pig, and some of the grue is reminiscent of the infamous Japanese horror film series of the same name.

The last two chapters beggar belief, and it’s impossible to read the conclusion with a straight face. “Doesn’t that hurt?” Mima asks when she’s confronted with a vision out of Un Chien Andalou. “Of course it hurts!” comes the irritable reply. Tommy Wiseau could have hardly wrecked things better, and he would be ideal casting for the Darling Rose in a more faithful version of the book.

In his afterword, Takeuchi pays generous tribute to Kon’s film, “the delight at seeing my own work nurtured and transformed into something so splendid”. And indeed, the anime got the author recognised by fans worldwide, as the man who wrote the book that inspired Perfect Blue. Unfortunately, now that his book is available in English, Takeuchi’s reputation may be about to take a knock.

Perfect Blue: Complete Metamorphosis is published by Seven Seas.

Leave a Reply