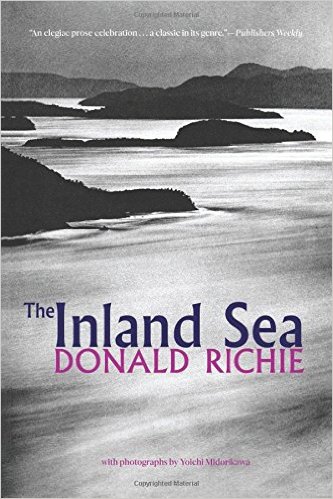

Books: The Inland Sea

July 24, 2017 · 0 comments

By Jasper Sharp.

If it weren’t for Donald Richie’s and Joseph L. Anderson’s invaluable The Japanese Film: Art and Industry (1959), the first book-length study on the subject in the English language, or Richie’s monographs The Films of Akira Kurosawa (1965) and Ozu: His Life and Films (1974), one wonders what the state of overseas appreciation or understanding about Japanese cinema might be. Curiously, Richie never regarded himself a film critic, but in more general terms as a writer, and more specifically a commentator and chronicler of the country that was his home for over 60 years until his death, aged 88, four years ago on 19th February 2013.

If it weren’t for Donald Richie’s and Joseph L. Anderson’s invaluable The Japanese Film: Art and Industry (1959), the first book-length study on the subject in the English language, or Richie’s monographs The Films of Akira Kurosawa (1965) and Ozu: His Life and Films (1974), one wonders what the state of overseas appreciation or understanding about Japanese cinema might be. Curiously, Richie never regarded himself a film critic, but in more general terms as a writer, and more specifically a commentator and chronicler of the country that was his home for over 60 years until his death, aged 88, four years ago on 19th February 2013.

Over the decades, Richie held court over such diverse topics as Japan’s history, literature, food, fashions, fads and phallic iconography. However, never one to play down his own presence in these mediations between East and West, some of his finest writing was on subjects with which he had a more personal acquaintance, such as Public People, Private People: Portraits of Some Japanese (1996) – the lyrical collection of character sketches of ranging from the esteemed novelists Yasunari Kawabata and Yukio Mishima, through movie icons like Toshiro Mifune and Zatoichi-star Shintaro Katsu, to the notorious pre-war femme castratrice who inspired Nagisa Oshima’s In the Realm of the Senses (1976), Sada Abe. He also wrote a candid memoir, The Japan Journals: 1947-2004 (2005), a gaijin’s-eye account of Japan’s dramatic post-war reconstruction, and social changes spanning the period since he first arrived as an early-20-something clerk typing inventories for the US occupying forces, through to the early years of the new millennium.

Considered his best work by many, including the author himself, is The Inland Sea (1971), a poetic travelogue detailing several months in the late-1960s spent voyaging amongst the islands and coastal towns of the stretch of water that separates three of Japan’s main islands, Honshu, Kyushu and Shikoku. Stone Bridge Press’s 2015 reissue, the fourth edition since its original publication, not only serves as a reminder of just how good Richie the writer could be, but also how good travel writing can be – something of a dying art in this global age when anyone can hop on a plane or train to an alien land and immediately post their thoughts and impressions on social media before they’ve had time to ferment.

Personally, I found it a fascinating work to revisit: not only was The Inland Sea published the same year I was born, but its author was around the same age as I am now when he wrote it. Clearly feeling very much the outsider after almost 20 years in Japan and smarting from the wounds left by a failed marriage to the American writer Mary Evans, there’s an understandable air of meditative mid-life melancholy. “I want to observe what people were like when they had time and space,” he writes of his break from the bustle of Tokyo, “because this will be one of the final opportunities.” The landscapes and seascapes of the area provide a natural foil for the author’s reflections on where both he and a country on the cusp of a new era of prosperity were headed.

“It is perhaps significant that the Japanese have long thought of it mainly in terms of navigability (a sea within straits) because – lying at the mercantile crossroads of the nation – it has always been something to get across rather than merely to enjoy,” he begins, in a narrative that sees him hopping across islands, musing upon his encounters with fishermen, innkeepers, war widows, schoolgirls and bored tour guides who, “cut off from each other and from the mainland … are like mountain villagers separated from the next village by whole ranges. They know much of their own island and nothing of the next, though it is framed daily in their bay.”

“It is perhaps significant that the Japanese have long thought of it mainly in terms of navigability (a sea within straits) because – lying at the mercantile crossroads of the nation – it has always been something to get across rather than merely to enjoy,” he begins, in a narrative that sees him hopping across islands, musing upon his encounters with fishermen, innkeepers, war widows, schoolgirls and bored tour guides who, “cut off from each other and from the mainland … are like mountain villagers separated from the next village by whole ranges. They know much of their own island and nothing of the next, though it is framed daily in their bay.”

Richie was responsible for introducing the concept of mono no aware to the West, that vague term (so often identified as a hallmark of the films of Ozu) used to express the transience of “things”, of natural phenomena such as the passing of the seasons. It is therefore no surprise that ideas of impermanence and metaphysical journeys should so permeate his written aesthetic. There’s an unembarrassed, self-confessed romanticism to his portrait of the island peoples thus far untouched from the “froth of novelty” he describes as contaminating the urban-based culture of the mainland. To Richie, the beauty of the region is tinged not so much by its past, but an awareness of what lies in the future. “Already the modern mainland is reaching out, converting each captured island into an industrial waste; already the fish, once so abundant, are leaving their annual paths, maintained over the centuries, and seeking clearer depths,” he writes. “In a few decades, however, the ruin will be complete.” At the same time, prior to his departure from the Honshu, he also notes “the excitement of watching change. Old and new in these small provincial cities continue to exist side by side, and the new is often built directly beside, rather than directly on top of. One may, for a time, compare; for space, see history in the gap. Very attractive to a heritage-starved, history-parched American.”

The Inland Sea is also testament to another important historical juncture, wedged between the pervasive myths of Ruth Benedict’s occupation-era anthropological study of the country she’d never even visited, The Chrysanthemum and the Sword: Patterns of Japanese Culture (1946), and Edward Said’s much-needed kick up the jacksie to centuries of white Eurocentric attempts at fixing foreign cultures in words and concepts, Orientalism (1978) – a book not specific to Japan, but certainly applicable to those writing about it. Richie’s explorations of the country’s timeless hinterlands perhaps might best be viewed as the flipside to Roland Barthes’ ludic attempt at articulating Japan through the language of semiotics in Empire of Signs (1970), published just before The Inland Sea, and based on a solitary trip to the country the Frenchman made in 1966. Rather than cold academic abstraction and bafflement, Richie very much foregrounds his own role in bringing this far-flung land closer to an imagined readership. Nevertheless, his ruminations about “Japan” and “the Japanese”, both in this book and elsewhere, might all too occasionally come across as tendentious and more than a little vacuous. His claim that “the Japanese are resolutely of the here and now, and this, to be sure, limits them” is one such nonsensical attribution that a writer of such stature would never get away with today. His later assertion that “Asia does not, I think, hoard and treasure life as we do” can be seen as particularly contentious given the rhetoric of some of his compatriot contemporaries surrounding the Vietnam war that was then in full swing.

Indeed, Richie has certainly courted his share of criticism over the years from more scholarly voices for his more superficial and essentialist readings of the country, but one also should keep in mind that he was never a scholar. His output was that of the self-educated, non-institutionalised first-person voice of the individual, now all but supplanted by the professionalised classes of academics, cultural gatekeepers and tastemakers. But while certainly guilty to a degree of “othering” the inhabitants of his adopted homeland, he was also not afraid of othering himself as a man for whom writing was not only integral to his process of trying to understand Japan, but also his place within it. As he confesses, “I live in this country as the water-insect lives in the pond, skating across the surface, not so much unmindful as incapable of seeing the depths.”

Richie’s voice is very much at the heart of his narrative – affable, rhetorical, rhapsodic and elegiac by turns – as he wends his way through the region’s traditional fishing villages, shrines, temples, a series of lacklustre tourist attractions and other varied locales like a secluded a leper colony and the village where Keisuke Kinoshita’s filmed Hideko Takamine in Twenty-Four Eyes (1954). As such, The Inland Sea is best read not as an anthropological or sociological account of a land and its people, but as an impressionistic stream-of-consciousness from a particular individual in a particular place at a particular point in time, a meditation on temporal and physical transition by a stranger in a strange land for whom the journey represented the furthest point of flight from his provincial birthplace in Lima, Ohio. It is a wonderful reminder of the joys of taking oneself out of one’s usual element, of the comfort of strangers, of drifting without fixed destination, and of those fleetingly satori moments of mindful self-awareness that snatch the solitary traveller, succinctly expressed at one point by Richie’s enunciation: “I am happy – happier than I have been for weeks or months… And I am happy because I am suddenly whole and know who I am. I am a man sitting in a boat and looking at a landscape.”

The Inland Sea by Donald Richie is published by Stone Bridge Press.

Leave a Reply