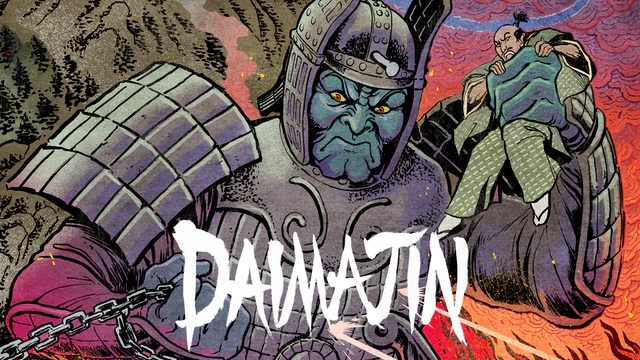

Daimajin

September 3, 2021 · 0 comments

By Tom Wilmot.

Despite a studio system in decline, monster movies continued to roar on into the Japanese film industry of the 1960s. While icons like Godzilla, Mothra, and many other gargantuan creatures dominated screens through studio Toho, rival studio Daiei threw their hat in the ring with the enduring Gamera series. However, while Daiei’s Tokyo studio churned out giant turtle movies aimed at kids, the Kyoto base was cooking up the Daimajin trilogy. With every entry shot and released within eight months during 1966, the films make up an overlooked if short-lived series. Much like Daiei’s Gamera films were last year, Daimajin has been given the full Arrow Video treatment, with the label releasing a colossal set worthy of the fearsome god.

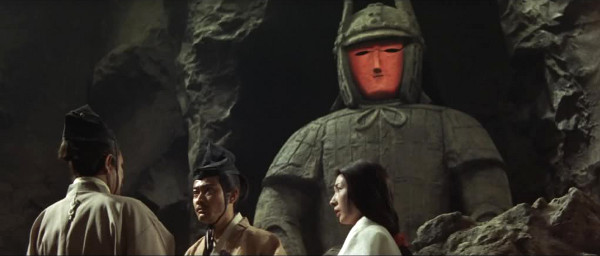

The plot of each Daimajin film is strikingly similar, with the same general framework being used for the entire series. The first two entries are the most alike, with the basic plot involving a distinctly evil faction taking control of an otherwise peaceful clan. The subsequent misdemeanours of this invading force, often quite sadistic, are met with unsuccessful resistance from the desperate locals, who look to their local god for salvation. Marking a slight change in direction, the third movie focuses on a group of village children who cross the cursed Majin mountain in a brave attempt to save their enslaved relatives. In every film in the trilogy, judgment comes courtesy of Daimajin, an ancient god in the form of a giant statue that wreaks merciless havoc on the overtly evil forces. It’s worth noting that each film takes place during the Sengoku (warring states) period of Japanese history, a chaotic 150 years or so during which numerous clans battled it out for power before the rise of the Tokugawa shogunate in the early 17th century.

First-time viewers of the franchise will be sure to notice that it takes an awfully long time for the titular god to make his explosive appearance. In fact, it’s not usually until around the last fifteen minutes that justice is served in one destructive form or another. However, far from being a drag until this climax, the Daimajin films are instead engaging chanbara (swordplay) flicks in their own right. You could even argue, as some experts do in the supplementals, that the movies belong more to the chanbara genre of samurai action films in which Daiei specialised, than the kaiju genre that often saw the featured monster dominate the screen from start to finish. In the first two entries of the franchise, in particular, there’s a fair amount of intrigue and entertainment to be found in the form of daring rescues, peasant rebellions, and thrilling samurai skirmishes. While most of these encounters see our heroes ultimately fail, they all help build-up to what tends to be an immensely cathartic finale.

In all three films the climactic appearance of Daimajin and the subsequent carnage that ensues is ferociously entertaining. The stern-looking god blasts apart everything in his path, whether it be fragile wooden gates, unavailing canons, or an array of terrified samurai. Daimajin’s triumphant arrival is gratifying in every entry, with the vengeful statue using several supernatural abilities to strike down evildoers, including conjuring whirlpools and calling down lightning. Wrath of Daimajin even sees the first use of the kami’s giant sword, which is hugely satisfying given that it’s left painfully untouched for the first two films. Without spoiling too much, the villains get their comeuppance in each movie, usually in a surprisingly violent manner that involves some form of poetic justice. While the antagonist’s demise is brutal in all three films, it’s arguably most enjoyable in Return of Daimajin, as the two warlords bringing misery to our heroes are especially despicable.

Of course, I would be remiss to discuss the Daimajin films without touching on the special effects, which come courtesy of seasoned SFX director Yoshiyuki Kuroda. One of the reasons that the Daimajin series came to fruition in the first place is because of the ambitions of Daiei to rival the tokusatsu (special effects) movies of other studios, specifically Toho. Thanks to the careful approach employed by Kuroda and a focus on achieving realism rather than just showcasing the special effects, the Daimajin films feature some of the most impressive visuals of the Showa era’s monster films. The detailed miniatures, seamless integration of blue screen and live-action, and the restraint shown regarding Daimajin’s appearances all work to make the vengeful god a far more convincing entity than one might expect from a 1960’s monster franchise. Even the more outlandish visual effects, such as the parting of the water in Return of Daimajin, are remarkably well-executed for the time, especially considering the production constraints Daiei would have had in comparison to a contemporary Hollywood studio.

Any Daimajin box set worth its salt would have an array of bonus features that further explore this mostly overlooked chapter in kaiju cinema, and as always, Arrow Video deliver. An introduction from critic Kim Newman touches on some of the influences behind the Daimajin series, notably the legend of the Golem, with Julien Duvivier’s 1936 film Le Golem being of particular inspiration. Newman also discusses the viability of the series and notes that the films are less of a trilogy in the traditional sense, as the narratives aren’t connected. One could indeed watch the movies in any order and not be confused, although you could argue that the progression of Daimajin’s abilities between films does add some level of continuity to the series.

Next up is a deep dive into the trilogy’s special effects through a video essay put together by Ed Godziszewski. The Japanese film historian takes us through the origin of Daimajin’s appearance, with the initial look coming from ancient ritual statues in Japan, called haniwa. Perhaps the most amusing detail behind the kami’s design is that his prominent cleft chin was directly inspired by none other than Kirk Douglas, though I can’t see much more resemblance to the golden age Hollywood star. Godziszewski also raises the curtain on more of the technicalities behind bringing Daimajin to life, paying special attention to the ¥10 million blue screen installed by Daiei that was, somewhat ironically, never used again once the trilogy was complete.

Further insight into the making of the Daimajin films is provided via a fascinating interview with the charming Professor Yoneo Ota, director of the Toy Film Museum in Kyoto (an institution well worth looking up for those interested in film history). Ota served as an equipment handler on Return of Daimajin during the summer of 1966 and was even involved in the resurrection of a Daimajin statue that, at one time, could be found at the entrance of Daiei’s Kyoto studio. As well as providing an interesting account of how Daiei Kyoto operated at the time of the Daimajin trilogy’s production, Ota also highlights the importance of storyboards to the making of the film. Remarkably, some storyboards for Return of Daimajin have survived and are available in this release as part of a side-by-side comparison with the final footage.

Also included in the set is an extensive archival interview with cinematographer Fujio Morita, who worked intimately on all three Daimajin films. The late cameraman, who passed away in 2014, worked on many features during his long career, including as an assistant cameraman on Akira Kurosawa’s Rashomon. He discusses everything from childhood memories of Nikkatsu’s old Kyoto studio to the difficulties posed by the Daimajin trilogy. The cameraman infamously worked himself into the ground during the production of the films with the project taking a significant toll on his health. This almost ninety-minute interview offers a wonderful look back at the career of one of Daiei’s greatest cinematographers.

There are also three audio commentaries included in Arrow’s set, with each film in the trilogy being given the complete supplemental treatment. Covering the first entry is Japanese film expert Stuart Galbraith IV, who talks about how the year of the trilogy’s release, 1966, was a significant one for tokusatsu media in general, what with the television debuts of Ultra Q and Ultraman, as well as several other fantasy film releases. In addition, Galbraith pays special attention to many of the lesser-known actors in the film and provides revealing quotes from performers involved in the production, including the likes of Yoshihiko Aoyama.

The commentary for Return of Daimajin is a joint effort from former Midnight Eye editors Tom Mes and Jasper Sharp. Both cinephiles have a deep understanding of the different periods of Japanese cinema history and do an excellent job of placing the Daimajin films within the context of their era. The most interesting tangent explored during their conversation focuses on the oddly neglected 1961 film Buddha, which marked Japanese cinema’s first foray into 70mm. Sharp, in particular, is in his element when discussing the more obscure features that are intimately connected to the fabric of Japanese film history.

Providing the commentary for Wrath of Daimajin is All the Anime’s very own Jonathan Clements. In a rather shocking revelation, Clements details that roughly 40 minutes of footage was lost from the film due to an accident at the developing lab just before the end of production. With this in mind, it’s a wonder that Wrath of Daimajin made it to Japanese theatres at all, let alone in a coherent state.

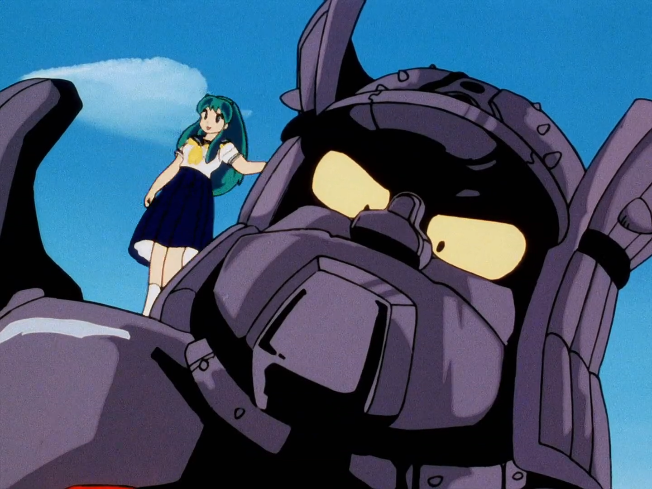

The release is rounded out by a mightily thick booklet that contains a selection of behind the scenes stills and a whopping seven informative essays that celebrate various aspects of the trilogy. Everything from the booming score from legendary composer Akira Ifukube to further details behind the special effects is discussed, as Clements and Godziszewski also lend their writing talents to add to their on-disc supplementals. Anime fans will be most interested in reading Kevin Derendorf’s record of Daimajin’s place in popular culture over the years, with the vengeful god appearing in various manga series and even showing up in an episode of the much-beloved Urusei Yatsura anime (specifically episode 162).

There are those who may pine for Daimajin’s return, with the brevity of the series perhaps being one of its most surprising aspects. A television adaptation of the first film did make its way to the small screen in 2010, but a feature return doesn’t seem likely any time soon. However, if these three movies are the only ones that will ever see the fearsome kami grace the silver screen, then they’re entirely worthy efforts. The Daimajin series is a remarkable feat of film in the context of 1960’s Japanese cinema, with the consistency in quality and the talent behind the camera meaning that the franchise is arguably the finest of studio Daiei’s monster films. Arrow Video’s limited edition boxset is a wonderful way to enjoy this unique batch of films, with exceptional effort having been made to make this the most comprehensive Daimajin release to date.

The Daimajin trilogy is released on Blu-ray by Arrow Video.

Leave a Reply