Fuse: Memoirs of the Hunter Girl

January 16, 2022 · 0 comments

By Andrew Osmond.

On one level, you can enjoy Fuse: Memoirs of the Hunter Girl as a cheerful period yarn about a perky girl who comes to samurai-era Tokyo and gets involved in an adventure with werewolves. It makes a very interesting comparison with Keiichi Hara’s Miss Hokusai; both films are set in 19th-century Tokyo, foregrounding the women in the shadows of celebrity male artists. But Fuse is also a fiendishly ‘meta’ movie, mixing authors with their fictional creations and riffing off a tale that’s been told many times before.

On one level, you can enjoy Fuse: Memoirs of the Hunter Girl as a cheerful period yarn about a perky girl who comes to samurai-era Tokyo and gets involved in an adventure with werewolves. It makes a very interesting comparison with Keiichi Hara’s Miss Hokusai; both films are set in 19th-century Tokyo, foregrounding the women in the shadows of celebrity male artists. But Fuse is also a fiendishly ‘meta’ movie, mixing authors with their fictional creations and riffing off a tale that’s been told many times before.

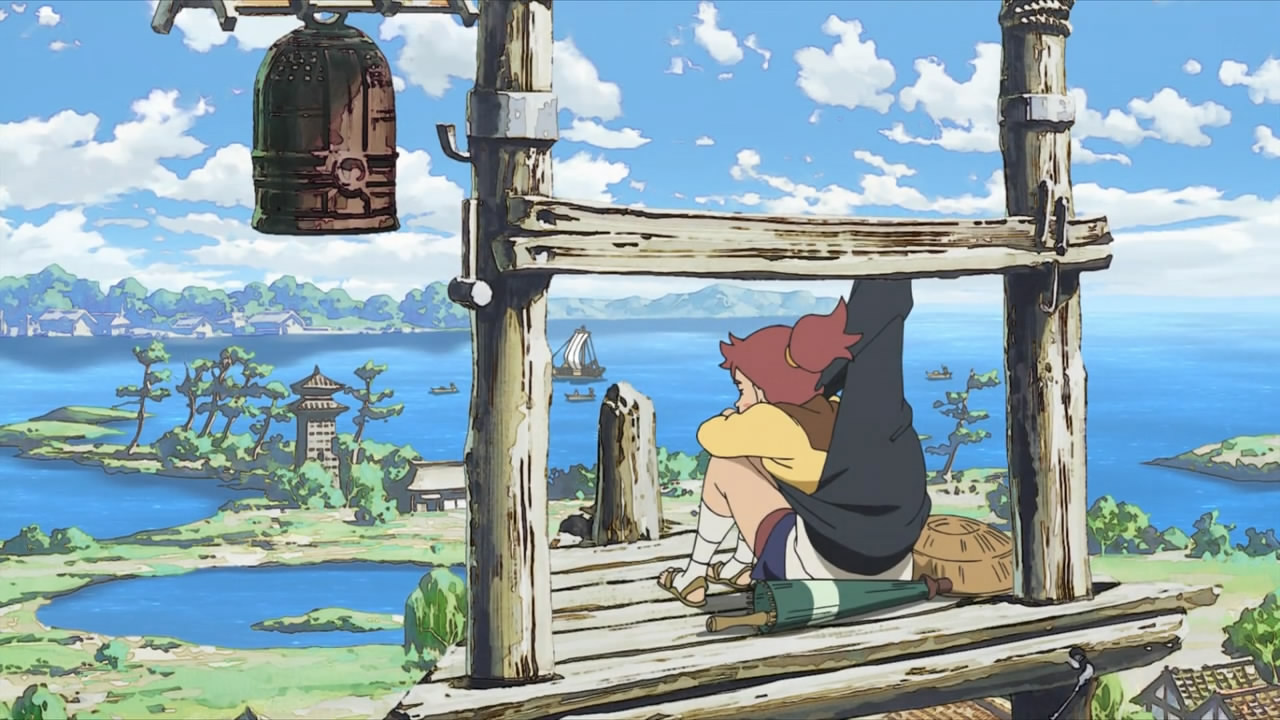

The huntress heroine in Fuse is Hamaji, a teenage girl who’s grown up in the mountains tutored by her grandfather, who’s recently died. She’s been taught to respect the beasts she tracks and kills, to honour their bond with her. Invited by her brother to Edo (the old name for Tokyo), Hamaji finds that the city is being plagued by “Fuse,” werewolves who are tearing their way through the citizenry. (“Fuse” combines the Japanese characters for man and dog.) However, the creatures are being hunted down one by one; of the original eight, only two are left. And as fate would have it, Hamaji soon meets a beautiful pale man who we, the audience, know is one of the last of the Fuse…

The film is directed by Masayuki Miyaji, who was very literally a disciple of Hayao Miyazaki. Miyaji was recruited by the anime legend onto a hothouse course for training up new directors. The course was almost as deadly as hunting werewolves; Miyaji had the task of waking Miyazaki from his afternoon naps! Yet Miyaji was one of the few survivors who passed the course, and became assistant director on the biggest anime film of all, Spirited Away.

And yet Miyaji’s Fuse is its own beast, with only fleeting echoes of Miyazaki and Ghibi. It’s animated by the venerable TMS Entertainment (formerly Tokyo Movie Shinsha), which is a studio that’s worked on scores of overseas production and can take on any style. Fuse was released to celebrate the ninetieth birthday of a literary magazine (Bungei Shinju), but the last thing it suggests is stodginess. It’s a cartooned, caricatured affair, leaning away from conventional cuteness. There’s lots of comic overacting and goofball expressions. Hamaji is a large-thighed tomboy, often taken for male, who looks positively stocky for anime, though there’s a My Fair Lady moment when she’s forced into a feminine kimono.

The brashly cartooned drawing suggests a nonconformist mindset like that behind Giovanni’s Island. Fuse’s unconventional, uncute look also suggests French comics and cartoons, spiced up with bawdy humour and blithe violence. (The film’s opening minutes are startlingly bloody for such a cheery looking film.) One shot takes the viewpoint of a newly severed head, sinking into a noisome ditch; beat that, Sylvain Chomet!

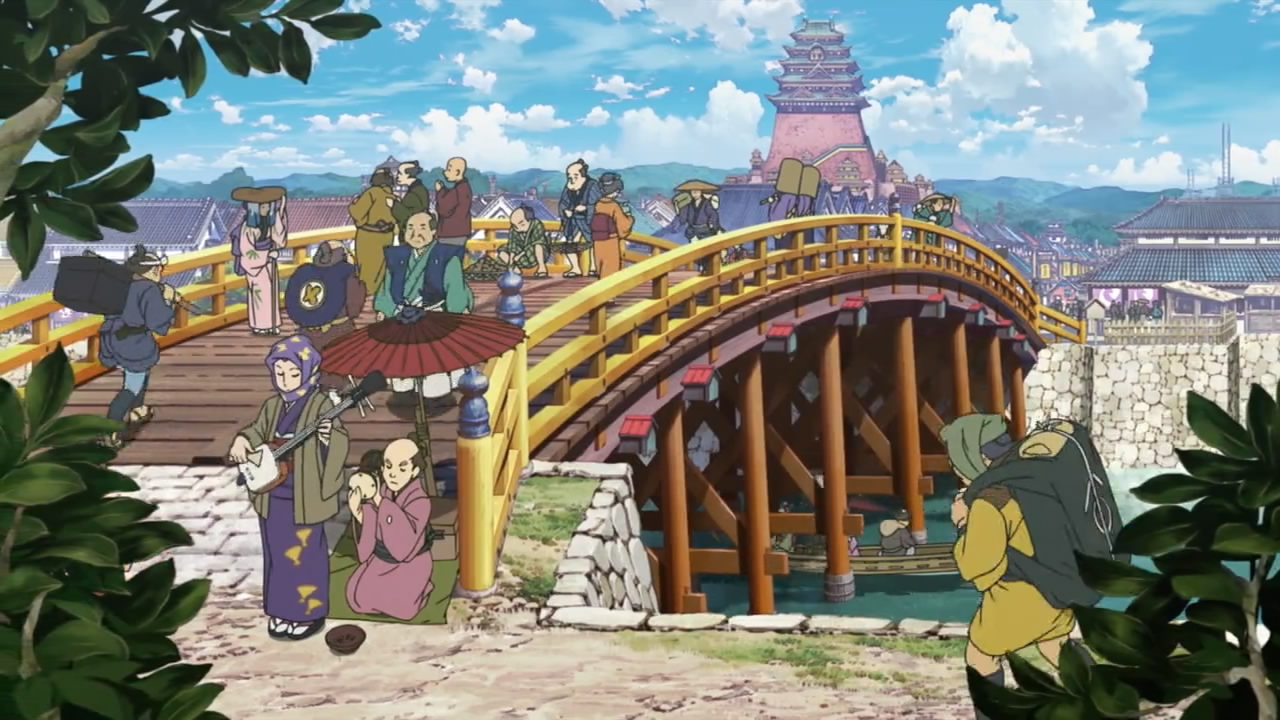

As mentioned earlier, Fuse has inadvertent crossovers with Miss Hokusai, in artistic themes and period backdrops. The films both feature the wooden Ryogoku bridge, as painted by Hokusai; Fuse’s first big battle climaxes there. Both films also feature the fabled Yoshiwara pleasure district, where a Fuse may be hiding out among the prostitutes and courtesans. This part of the film may also remind viewers of an SF classic, Blade Runner, where a hunter stumbles on an exotic woman performer who’s more than she seems.

As mentioned earlier, Fuse has inadvertent crossovers with Miss Hokusai, in artistic themes and period backdrops. The films both feature the wooden Ryogoku bridge, as painted by Hokusai; Fuse’s first big battle climaxes there. Both films also feature the fabled Yoshiwara pleasure district, where a Fuse may be hiding out among the prostitutes and courtesans. This part of the film may also remind viewers of an SF classic, Blade Runner, where a hunter stumbles on an exotic woman performer who’s more than she seems.

But if you’re talking about Fuse, you need to talk about the novel which underpins it, The Hakkenden. Actually it’s not just a novel but a saga, serialised over decades in the nineteenth century (1814 to 1842). It was written by Kyokutei Bakin, a samurai who wanted to instil Confucian virtues in his readers. Part of the story is retold for the film’s characters at a kabuki performance, depicting the forbidden union between a princess and her faithful dog. (Yes, you read that right.) This particular bit of the story – perhaps inspired by a Chinese myth – is echoed in Richard Corben’s US indy comic Rowlf, which was an influence on Miyazaki’s Nausicaa. It may also lurk behind Mamoru Hosoda’s Wolf Children, in which a woman consummates her relationship with a werewolf while he’s in canine form.

The main Hakkenden story is about eight warriors descended from the princess and the dog. These heroic scions can be identified by birthmarks in the shape of eight-segmented peony flowers. The warriors’ adventures have been told a great many times – this is a point stressed within Fuse, which shows the story is already spreading through multiple tellings, ‘counterfeit’ versions, in Edo-era Tokyo.

Depending on their age, Fuse’s Japanese audiences may know Hakkenden from a celebrated TV puppet serial in the early 1970s; a 1983 live-action movie by Kinji Fukasaku (Battle Royale); a video anime version in 1990; and many other versions, taking the story wildly different ways. In this respect, the Hakkenden novel is comparable to the Chinese novel Journey to the West or Monkey, which mutated into everything from campy Japanese live-action TV epics to Dragon Ball.

Depending on their age, Fuse’s Japanese audiences may know Hakkenden from a celebrated TV puppet serial in the early 1970s; a 1983 live-action movie by Kinji Fukasaku (Battle Royale); a video anime version in 1990; and many other versions, taking the story wildly different ways. In this respect, the Hakkenden novel is comparable to the Chinese novel Journey to the West or Monkey, which mutated into everything from campy Japanese live-action TV epics to Dragon Ball.

Fuse is directly adapted from one of the many modern riffs on Hakkenden, a novel by the female author Kazuki Sakuraba, who also wrote the Gosick light novels animated by Bones. The film’s screenplay is by Ikirou Okouchi, who wrote the Berserk films and was one of the main collaborators on Code Geass. Whereas the original Hakkenden was set many centuries ago, in Japan’s “Sengoku” period, Fuse’s story takes place at the time Hakkenden was actually being written. Kyokutei Bakin, the author, appears in Fuse as a supporting character, but the film is more interested in his granddaughter, Meido Bakin, who’s shown as a geek with glasses, giggling as she invents… her own unauthorised riff on Hakkenden,.

In other words, Fuse is a movie that knocks down its own fourth wall and places two writers – Kyokutei and his granddaughter Meido – in a modern mutation of a story that they’re writing – or rather, competing to write! The literary play is done very lightly, more Shakespeare in Love than Charlie Kaufman, but the film repays repeat viewings to catch the subtleties. For example, the story is bookended with images of Meido in her act of creation, putting ink-brush to paper. The film is also looking back at Hakkenden from the perspective of a modern day audience who knows what the next century and a half will bring. Hakkenden, remember, was written a few scant years before Japan opened up to the world, letting in foreign ‘monsters’ as frightening as werewolves and changing the country forever.

Andrew Osmond is the author of 100 Animated Feature Films. Fuse: Memoirs of the Hunter Girl is released in the UK by Anime Limited.

Leave a Reply