Kill la Kill

February 11, 2021 · 0 comments

By Jeannette Ng.

Kill la Kill rests on a panoply of ridiculous puns, the central pair of which work just as well in English due to them being loanwords: “fascist” and “fashion” do sound very similar. The title itself plays on another set of puns that only really works in Japanese: “to kill” (キル kiru), “to cut” (切る kiru) and “to wear” (着るkiru). Which leads, naturally, to an anime about the fight to topple a fascist regime where the primary weapons of war are school uniforms that grant super-powers, and which need to be cut from the bodies of the wearers.

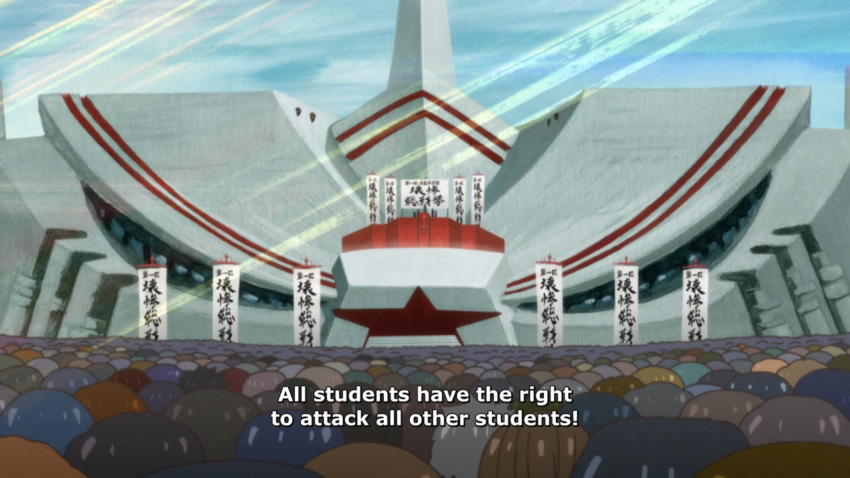

The story begins in a fortress high school, Honnouji Academy, which sits atop a rigidly tiered city with the slums at the bottom. We follow Ryuko Matoi, a transfer student determined to tear the school apart in search for answers regarding her father’s murder. Clothing, power and identity are intertwined in this world but conveniently, Ryuko’s weapon of choice is half a pair of enormous scissors – she here to sever all these connections.

Fashion and fascism may seem randomly unconnected on the surface, but they are very much bound together in the real world. Hugo Boss designed those infamously dapper SS uniforms, after all, and Coco Chanel was a Nazi agent. Moreover, fascism hinges on the aestheticisation of politics, where spectacle and pageantry distract from the horror and loss of fundamental rights, whereas fashion is nothing but aesthetics.

There is nothing subtle about Kill la Kill’s approach to this – the anime literally opens with a history lesson about the rise of the Nazi party, a juxtaposition that becomes all the more stark as the narrative repeatedly returns to those lessons.

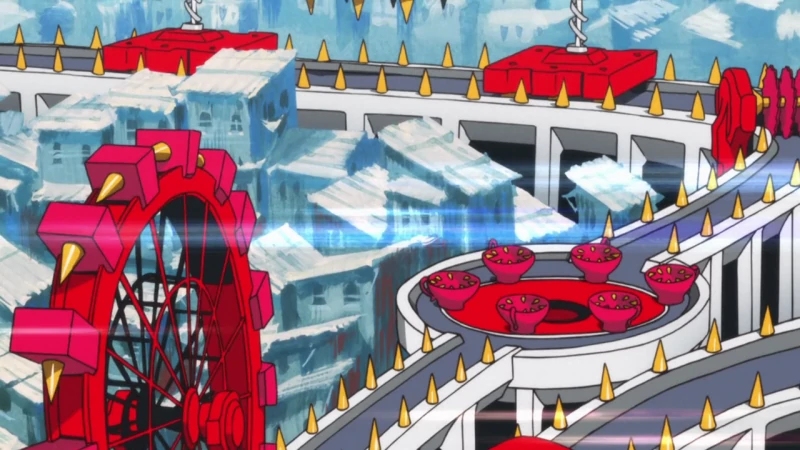

Allegory, metaphor and puns are all made literal in the most blunt and brutal way possible. “No Tardies Day” sees the transformation of the entire city into an obstacle course of death which needs to be traversed by Ryuko and her friend Mako Mankanshoku in order not to be expelled. The privileged students have access to a cable car that allows them to glide above the scrambling unwashed masses in an incredibly visceral metaphor, but some viewers might overlook that in between all the jokes about Ryuko being stuck in rabbit pyjamas too small for her and accidentally flashing everyone.

Which only prompts the central question of any piece of writing about Kill la Kill – is this anime very, very stupid or very, very smart?

For the uninitiated, “fan service” often refers to salacious content, added to endear a piece of media to its fans. It is a term that crossed over into wider western geekery, where it has parallels in referring to a busty female character in children’s media being something “for the dads.”

As bluntly as possible: people (especially men) like putting sexy undressed characters (especially women) in their media, but every now and again, some combination of shame, prudishness and narrative logic strikes and there is a desire to justify the lack of clothes. So, we have Hideo Kojima telling everyone that the assassin, Quiet, must wear a bikini because she breathes through her skin.

This isn’t restricted to Japanese media, of course. DC’s Powergirl has stated that her iconic boob window symbolises her internal emptiness and refusal to be a distaff counterpart to Superman. In Thomas Hardy’s “A Pair of Blue Eyes”, Elfride creates a knotted rope of her undergarments in order to rescue the novel’s hero, Knight, who has fallen off a cliff. She then runs off in only her diaphanous dress, allowing Knight the intimacy of examining her under-things.

So perhaps we should ask a different question of Kill la Kill. Can a piece of art still be an incisive satire when it is committing all of the sins it is simultaneously calling out… just MORE?

“More” is the operative word in Kill la Kill. It piles on philosophical musings and weighty themes atop its narrative contrivance, all in the service of getting its characters into successively more skimpy outfits. And out of those outfits, as the resistance group is named Nudist Beach. Aikuro Mikisugi, the undercover agent posing as a teacher, strips off his shirt in front of streaming sunlight whenever he explains the plot (giving new meaning to the portmanteau “sexposition”). An extremely revealing battle uniform is named “Purity” and is repeatedly called a “wedding dress” by its wearer as she gives a speech about how shame only holds her back.

At once a cheap pun and an excuse to get animated girls into butt-jigglingly tiny outfits, the battle uniforms are also central to an elaborate and convoluted science fiction conspiracy. Which is, as said, the joke. There must always be more explanation and more grandiose speeches.

The puns return in force, not just in the plays on “school uniform” (制服 seifuku) and “conquest” (征服 seifuku), but also in visual accompaniment to the elaborate speeches given by Mako. Every episode or so, against a spot-lit background, Mako gives a big speech and mimes out things that pun with the isolated words in that speech, in between general flailing and crude gestures. One moment she is naked on a sushi boat and the next she is in full armour atop a chibi stallion. The effect is chaotic, hilarious and absolutely absurd. Which are also words that apply to the whole of Kill la Kill.

As a jumble of striking, surreal and unashamedly sexual images, Kill la Kill is unrelenting, even as one gets stylistic whiplash between the pervert humour, the cost-saving stillness of the expositions and then back to the swooping camera work around the frantic fights. Even as its first few episodes appear to set up a simple tournament structure of Ryuko battling each of Honnouji Academy‘s club presidents and sports team captains in turn, the anime swiftly abandons this in the favour of more plot twists, additional antagonists and seemingly random digressions.

Jeannette Ng is the author of Under the Pendulum Sun. Kill la Kill is released in the UK by Anime Limited.

Leave a Reply