Mai Mai Miracle: The Origins

December 19, 2017 · 0 comments

By Andrew Osmond.

In 2009, Mai Mai Miracle’s director Sunao Kutabuchi released an unusual adjunct to his film, a self-published free magazine called The Days Blown By Mai Mai Miracle. It included his account of the origins and development of the story.

In 2009, Mai Mai Miracle’s director Sunao Kutabuchi released an unusual adjunct to his film, a self-published free magazine called The Days Blown By Mai Mai Miracle. It included his account of the origins and development of the story.

As the director explained, Mai Mai Miracle had several starting points. One was a story outline that Katabuchi had come up with himself in 2002. This was shortly after he had directed his first feature film, the family-oriented Princess Arete, in 2001.

The outline, which has obvious similarities to Mai Mai Miracle, runs as follows:

The outline, which has obvious similarities to Mai Mai Miracle, runs as follows:

“The main characters are two girls. One grows up in the country, and the other grows up in the city, without her mother. The country girl comes to town. She talks about the landscape of her hometown, the people, the animals, and so on, to show off various images that influence the city girl, before she moves out.

“The city girl tries to catch up with the friend and gathers up all she could remember of the country girl’s story, trying to make it hers. A while later, they meet again. Although she did not believe she could run that much, the city girl runs. Her liveliness is more precious than anything else.”

“I tried hard to push the project until spring the following year,” Katabuchi wrote. “Every time a project falls through, I feel pain. Such characters who were born and about to be raised disappear into thin air as if they never existed. I feel sorry for them. How many characters do I have to take to the grave as the memory of lost projects?”

Another starting-point was an experience Katabuchi had during this time. In October 2001, he was contacted by a friend, an amateur historian who was researching a fourteenth-century battleground. The site was near Katabuchi’s house and he and his friend went exploring by car. Katabuchi described the experience:

“I drove my little car through winding roads and historically resonant place-names started to appear one after another: Seizoroi Bashi (Full Force Bridge), Seishiga Bashi (Pledge Allegiance Bridge) and Shirohata Zuka (White Flag Mound). On that day, we could trace a 670-year-old road simply by reading the topography… We erased from our minds the new towns that had appeared since the beginning of the Edo Period, leaving only villages that must have existed before. We read the rises and falls of the landscape…

“After seven hours of wandering, by the time we returned home at dusk the whole landscape had changed for us. I felt like I could see two different time periods overlapping. It was a wonderful, exciting feeling.”

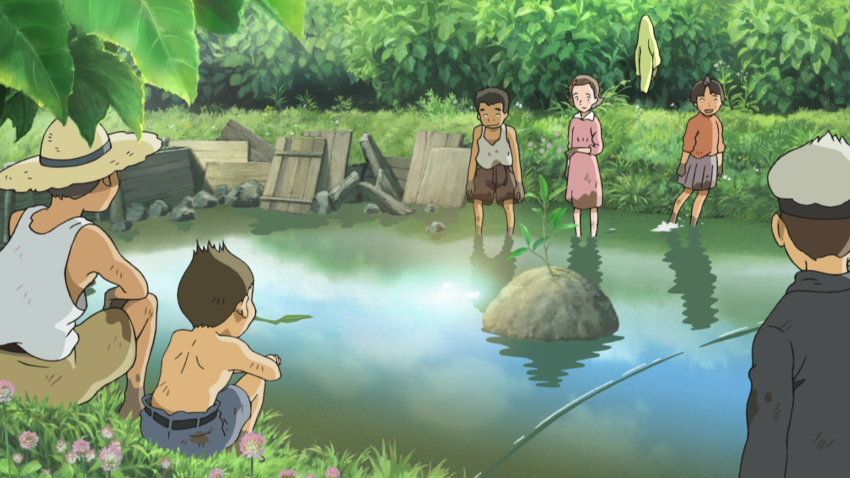

This experience is evident in Mai Mai Miracle’s scenes of Shinko, and later Kiiko, joyously exploring the lost landscapes of their home.

This experience is evident in Mai Mai Miracle’s scenes of Shinko, and later Kiiko, joyously exploring the lost landscapes of their home.

The third starting-point for the film was, of course, Mai Mai Shinko, a book of short stories about a country childhood, by Nobuko Takagi. It was published in September 2004. That November, Katabuchi was invited by the staff of Studio Madhouse to think about an adaptation. Katabuchi read Takagi’s book, and later made notes of his impressions:

“A straight path through swaying green wheat plants.

An isolated house like a ship on the sea.

The world is dominated by green.

Sometimes, white light glimmers from the river or a roof.

Shinko is easily carried away, but that’s just the way she is. She might seem different on the surface…

Maybe if it is like [Akira Kurosawa’s] Dodes’ka-den, it might work. [Made in 1970, Dodes’ka-den was Akira Kurosawa’s first colour picture; one of its characters is a boy who lives on a rubbish dump, immersed in fantasy.]

Leaving the ship-like house, her journey to the riverside, is full of imagination.

A boy, Shigeru, appears and the reverie ends. A bit embarrassing. Slight cheeky revenge towards Shigeru pops into her mind.”

(In the final film, it is Kiiko rather than Shinko who’s embarrassed by the appearance of Shigeru.)

Katabuchi particularly pondered one of the recurring themes in Takagi’s stories – death, and how to approach it in a film which could still uplift the audience. “If we are raising a voice to say that life is not full of sadness,” he wrote, “and that we should embrace the joy of life, in the middle of a nihilistic situation centred on death, we have to turn a negative moment into something somehow positive.”

Eventually, Katabuchi hit on a core for the film. This was an episode involving a goldfish, the eleventh chapter in Takagi’s book. “I felt that it showed the children’s desire to deny that death had happened, when facing it for real for the first time in their lives. Previously, for them, it had only been a distant concept… When they feel it in their body, children try hard to deny death. I might be able to make it into a film using [the goldfish story] as the central core.”

Eventually, Katabuchi hit on a core for the film. This was an episode involving a goldfish, the eleventh chapter in Takagi’s book. “I felt that it showed the children’s desire to deny that death had happened, when facing it for real for the first time in their lives. Previously, for them, it had only been a distant concept… When they feel it in their body, children try hard to deny death. I might be able to make it into a film using [the goldfish story] as the central core.”

However, Katabuchi did not want this episode to be the film’s climax. Instead, he wanted to “throw in a children’s internal adventure like the one in [Rob Reiner’s] Stand by Me.” That film has four boys embarking on a dangerous cross-country expedition; compare the journey of Shinko and Tatsuyoshi in the last act of Mai Mai Miracle. One of Katabuchi’s alternative ideas was to have Shinko run away from home accompanied by an imaginary friend – the James Dean character from the 1955 film East of Eden.

Katabuchi was also making links with his own ‘lost’ story about two girls, and with his own exhilarating drive through history. “[The girls] were recalled and overlaid on Shinko and Kiiko… Kotaro [Shinko’s grandfather] tells Shinko that their wheat fields were once the capital of a country a thousand years ago, pointing at the river that flows at a right angle. I myself traced a road that existed 670 years ago… Shinko, who can tell such story, may be a girl who has the ability to leap a thousand years of time.”

Andrew Osmond is the author of 100 Animated Feature Films. Mai Mai Miracle is released in the UK by Anime Limited.

Leave a Reply