Manga: A Silent Voice

October 12, 2021 · 1 comment

By Jeannette Ng.

I was running out of To Your Eternity (also by Yoshitoki Oima), which I was also absolutely loving, so I thought I’d read about the adventures of Shoya Ishida, repentant class bully. My interest in redemption arcs tends towards the melodramatic and fantastical – grand, blood-drenched villains who discover their heart of gold after have chewed up all available scenery rather than a sixth-grade bully. The idea that A Silent Voice is about a boy who bullied a deaf girl seems rather mundane and faintly off-putting on paper, but it’s one of those emotionally devastating manga character studies that just sneaks up on you.

After a brief framing narrative, most of volume one follows an easily bored Shoya spinning out of control. Nothing holds his attention and his friends are fast outgrowing his rambunctious, daredevil antics, making him all the more impatient and reckless. Shoya seems to think the way to hold onto his friendships is to escalate, to pull bigger, more dangerous stunts, but that only serves to alienate them. Everything is changing and he doesn’t like it. He spends the rest of the volume as this restless ball of reactive emotions. His fascination with the new transfer student, Shoko Nishimiya, quickly turns to a vicious hatred as he comes to blame her for every uncomfortable change in his own life. He is all too ready to embrace being the bully and the power that comes with it. That way, he cannot possibly be himself: a hated outcast.

Bullying is often depicting in teen media, especially in English-language media, as the purview of an elite few. The mean girls, the catty cheerleaders, the violent jocks. There is a pure, almost childish simplicity to those stories, but what A Silent Voice offers, and what I found so compelling about it, is that it offers complexity without ever losing sight of who the victim really is and who is being harmed. It’s not some sort of ridiculous gotcha or role reversal where the bully turns out to be a different kind of victim. It’s not seeking to absolve its characters through misunderstanding or contrivance. Nor is it clumsily making excuses, yanking on heartstrings through a tragic backstory. It’s just giving each of these characters space to speak and show their point of view. Class 6-2 is not a simple hierarchy reigned over by an all-powerful tyrant of a bully who simply needs to be dethroned. Things feel messy, peer pressure is confusing, overwhelming and the sense of self can suddenly be slippery. Each subsequent volume layers on more detail and perspective, flashbacks building on each other, the non-linear narrative carefully controlling each revelation, each epiphany. As the reunited Shoya and Shoko reacquaint themselves with their old classmates, there is an examination of old wounds, old guilt and the question of who is and isn’t complicit. There is a delicate dance of sympathies. Everyone is at once young enough to be forgiven but old enough to know better.

Shoya, especially, is the uncomfortable sort of bully that it is all too easy to see in myself. Every careless, cruel remark I’ve ever made suddenly surfaces in my mind. I always saw myself as pathetically bullied and unliked at school, but being older now, I can also look back and see all the times I’ve been dismissive, sarcastic and mean, however fleetingly. I’d like to think I didn’t give in to those flashes of anger, but knowing I could have is enough.

Though the first volume remains primarily about and from the point of view of Shoya, in the edges of his story, we can glimpse Shoko’s own perspective: her resilience, her optimism and very much the weight of other people’s judgements. Her mother wants to keep her safe, even if it goes against Shoko’s own desires. This is all epitomised in a moment where she asks the hairdresser (who also happens to be Shoya’s mother) to give Shoko a boyish haircut, believing this might stop her being bullied.

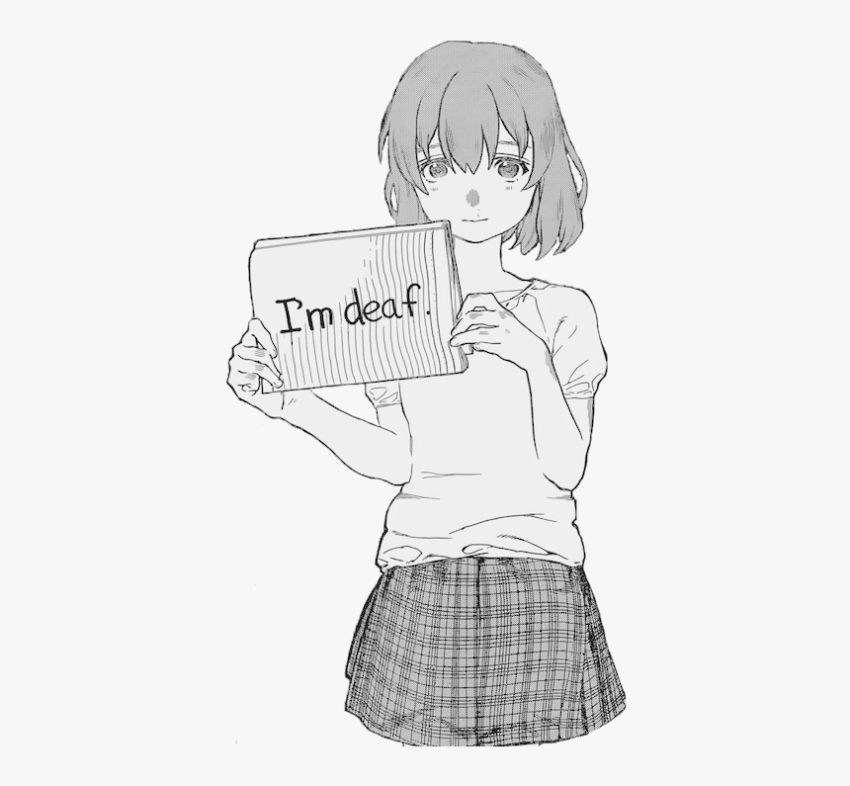

Also thematically significant is the exchange where a teacher proposes that the class learns sign language to communicate with Shoko. The class ends up openly debating why they should learn sign language when writing in Shoko’s notebook seems functional enough and so much more convenient to them. The ableism is obvious and palpable, but it also reiterates the importance of voices, as echoed in the manga’s title. Time and again we return to the question of who does and doesn’t actually listen to Shoko, as well as the voices she preserves in her battered but treasured notebook.

By the second volume, we are back to the present, where a repentant, teenaged and suicidal Shoya has learnt sign language and is trying to make amends, in between brooding over the semantics of friendship. He is clawing his way out of a depressive pit that feels again, all too familiar to me, along with those little coincidences, the flashes of hope and connection that keep you going. Though what is ultimately propelling him is neither, but instead a feeling of guilt. As though in reply to every single “a single act of redemption and then death is too neat and easy, true atonement must be earned through a lifetime of action” think-piece about villainy, Shoya is compelled to live on through his own melodramatic sense of guilt and obligation. Whenever it might seem that the two loneliest people in the universe have found each other – a motif evoked by that double spread of them staring at each other across the darkness of outer space the first time they meet – things get just that little bit more complicated. One more ghost from the past, one more misunderstanding, one more well-meaning interruption. One more buried crush. One more spike of silly, self-sabotaging self-hatred.

A motif of falling recurs in A Silent Voice, starting with Shoya’s care-free, daredevil plunges into the river in the first chapters. Each subsequent fall is far less pleasant, from Shoya being pushed into the river, to Shoko leaping to rescue her notebook and of course, Shoya’s own dark plans to end his life.

The art has a sharpness to it, as well as a compelling, expressive fluidity. Special attention is given over to hands, especially when they are “speaking”. Compare this to the anime version, directed by Naoko Yamada, in which sound, or its absence, became a new theme. What is particularly memorable in the manga are the way certain emotions are starkly expressed. The Xs on people’s faces when Shoya is withdrawn is a strangely visceral way to visualise his sense of isolation. There is a deeply unsettling sense of non-people-ness that is conveyed through those Xs.

In summary, all this sounds utterly melodramatic, but A Silent Voice reads as a surprisingly subdued tale, even with its flashes of comedic shenanigans among the side characters. Shoya’s mother in particular is an absolute delight – there is something that feels very true to me in the way it depicts the struggles with suicidal ideation, depression and that awful climb out of that pit. Especially when you feel like you deserve to be there.

Jeannette Ng is the author of Under the Pendulum Sun. A Silent Voice, the manga, is published in English by Kodansha, and can be found at the Azuki digital manga café.

Nathaniel L Boyce

January 31, 2023 2:39 am

I recently found this movie, and really appreciate your thoughts on it.