No Returns

June 14, 2021 · 0 comments

By Jeannette Ng.

Alice in Wonderland remains a towering influence on fantasy, both in English and in Japanese. Europe-inspired fantasy lands can take on new meaning in a Japanese media fascinated with the strange and exotic West, where even Paris and London can sometimes seem like alternate dimensions. Anime adaptations of English children’s classics, often with undertones of portal fantasy, are plentiful enough to be their own subgenre, including well-known works like Mary and the Witch’s Flower and Howl’s Moving Castle.

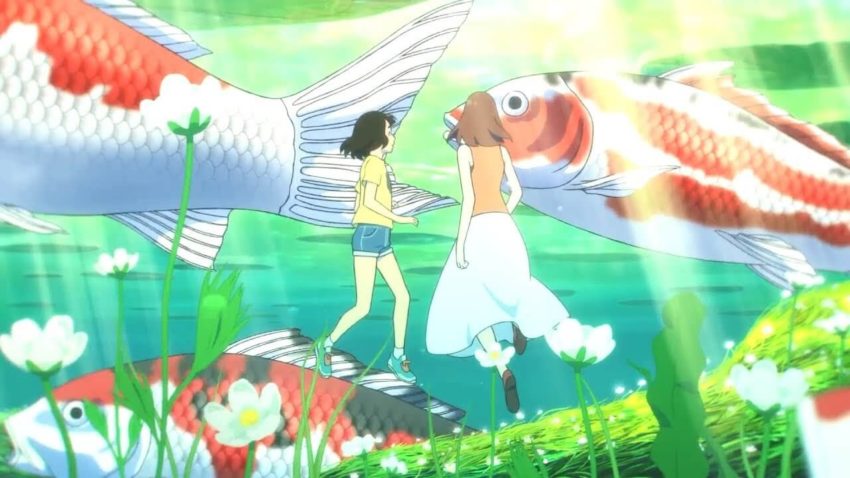

Alice’s effect on Japanese portal fantasy does not merely come through the popularity of its translations or adaptations. It, along with Mary Poppins and the Narnia books, has been cited as a huge influence on the works of the author Sachiko Kashiwaba, who packed her heroines off to parallel worlds in the 1970s and 1980s including the titular Birthday Wonderland (pictured above). Kashiwaba’s other-worldly adventures, which came to dominate the Japanese field, set the tone for much traditional fantasy… until a new generation reared on videogames and manga swarmed in to take over. And many of these younger writers didn’t get the memo about the need to come home again. They wanted to stay in their fantasy world for ever and ever.

Portal fantasies have taken the Japanese light novel, manga and anime genres by storm in the last decade, and it might be said to be experiencing the glimmerings of a renaissance in English, as well. But despite sharing some of the same roots, the genre has taken a rather different evolutionary path in Japanese.

In English, portal fantasy is usually built around a protagonist’s return to their original home (usually contemporary Earth). This compulsion to return provides the initial, if not central, thread to guide the displaced characters through the plot. As they unwittingly trap themselves in another world, they need to first dispatch more immediate and imminent threats, or solve whatever evil is plaguing the other world before they can return. Either way, the engine of the plot remains a desire for a return to the mundane, even as it may run parallel to a desire to explore and experience the strange.

A whole world of reasons lead to this convergence on the Return as important to portal fantasy. There is, for example, the towering influence of Joseph Campbell’s great monomyth which ends with the Hero’s Return from the world of adventure. Especially prominent in children’s fiction is the fashion to write up games of make-believe as adventures that happen to children, such as in J. M. Barrie’s Peter Pan or even Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland.

Sometimes, the protagonist’s journey can mirror the reader’s own literary visit into another world, such as in The NeverEnding Story (written originally in German, but a staple of English-speaking fantasy today — pictured), where the act of reading transports a bored child into the strange and alluring land of Fantasia. Central to The NeverEnding Story is the idea that reading can take us to a whole other world, but all books must end, forcing us to come back to reality. This relationship with other worlds paralleling a relationship with fiction is also seen in Sachiko Kashiwaba’s work, where children revisit adventures that their parents once had and fairy-tale characters stumble from their books to find out what became of their readers.

The Return also features in Japanese portal fantasy (often called isekai, literally meaning “other world”). Serials like Escaflowne, Inuyasha and more recently The Water Dragon’s Bride are all structured around their respective teenage girls falling into fantastical other worlds, trying to get back and stumbling into love along the way. And there are of course the “trapped in a video game” subgenre, spearheaded by the infamous Sword Art Online, which is also often credited for being at the forefront of the crushing dominance of portal fantasy in Japanese light novels and manga. But even within this subgenre we might see a trend that moves away from the importance of the “return”, away from escape to simply surviving and even making a new life within the game world, like Log Horizon or Overlord.

Anime’s most famous fantasy is arguably the Oscar-winning Spirited Away, although it, too, owes something of a debt to the works of Sachiko Kashiwaba. Hayao Miyazaki even began negotiations to adapt Kashiwaba’s novel The Marvelous Village Veiled in Mist in 1998 – a familiar-sounding tale about a troubled young girl finding herself through hard work in a fantastical otherworld. So familiar, in fact, that while Kashiwaba remained discreetly silent on the matter, her illustrator Kozaburo Takekawa accused Miyazaki of plagiarism where he gave up on the Village Veiled in Mist project and instead wrote Spirited Away (pictured). The controversy was complicated by Miyazaki’s open acknowledgement of Kashiwaba as an inspiration, and the publisher’s obvious desire to capitalise on the renewed interest. A new illustrator was brought on and the scandal was quietly brushed under the rug, as the The Marvelous Village Veiled in Mist was now rechristened the book that “inspired” the Ghibli classic.

Despite being the most widely known example of Japanese portal fantasy and having topped many a “best of isekai” list, Spirited Away also stands apart from vast swathes of contemporary Japanese portal fantasy. The distinction emerging seems far less to do with an East versus West sensibility and far more to do with one cluster of coming-of-age stories written for children, and another of escapist power-fantasy tales written for adults and teens.

Unlike most English fantasies, a conspicuously large group of Japanese portal stories feature a set-up in which any return is simply impossible because the central character is already dead in our world. There were rare examples back in the twentieth century in both English and Japanese – C.S. Lewis’s The Last Battle had its leading characters finding a new and eternal abode beyond both Narnia and Earth, and one character does not return from Kenji Miyazawa’s Night on the Galactic Railroad (pictured), for example. But in both those cases, death is the end. In oodles of contemporary light novels in Japan, death is the beginning, and our protagonist awakens in the otherworld as someone else. Instead of falling through a two-way doorway, they are reincarnated into another world, often into a radically different form.

This article isn’t exactly a taxonomy of isekai tropes so I will merely point vaguely at the variants involving protagonists in another world suddenly remembering their past lives after a dramatic fall or illness (My Next Life as a Villainess: All Routes Lead to Doom), as well as the ever popular hero-summoning rituals that fantastical religions seem to be constantly building themselves around (The Rising of Shield Hero, The Saint’s Magic Power is Omnipotent, How a Realist Hero Rebuilt the Kingdom). Summoning heroes isn’t unique to Japanese portal fantasy, of course, as J. V. Jones’ The Barbed Coil has a heroine manipulated through magic to stumble upon the titular coil and fall through worlds.

But this shift away from the Return is what makes the Japanese portal fantasy fascinating to me. The change may seem subtle but it opens up a whole slew of different themes. Many of these protagonists have left their old lives behind, leaving the story to focus wholly on engaging with their new surroundings. It is not that they are offered a choice or that that the two worlds represent a duality of the self or a temporary escape. Ascendance of a Bookworm’s Myne throws herself into the creation of books in a world without printing or widespread literacy (pictured). So I’m a Spider, So What? sees its newly arachnoid heroine gorging herself on dead monsters and learning dark magics for her own survival.

All this frees the otherworld from being a metaphor for childhood wonder or the last step in a journey towards adulthood. There is no lingering look back as the protagonists learn to let go of childish things. Instead, the exile of the protagonist from our world functions more like an invitation to delve deeply into intricate and bizarre lands, living out an entirely separate life. Without the pressing need to return, the indulgence of the power fantasy and escapism is distilled, if not refined.

There are outliers in Anglophone fantasy, of course. Adult characters, often depressed and undergoing some sort of mid-life crisis (or in one famous case, leprosy!), are far more likely to be allowed to make a new life in another world. Terry Brooks’ Magic Kingdom for Sale — Sold! has a lawyer answer an advert only to find himself trying to restore a magical kingdom, something that he has in common with many light novel heroes. L. E. Modesitt’s The Spellsong Cycle sees its heroine transported to another world where her knowledge of music suddenly makes her the most powerful sorceress in the world.

Mundane skills gaining new and powerful dimensions in the other world is also a common trope in Japanese portal fantasy, as the fantasy worlds are often trapped in a medieval understanding of science and society. How a Realist Hero Rebuilt the Kingdom (pictured) has a protagonist make use of his humanities degree, as well as teaching elves about forest management.

Everyday pleasures that we take for granted in the modern world are recontextualised as superpowers. In Another World with My Smartphone has a startlingly self-explanatory premise. Campfire Cooking in Another World with My Absurd Skill features a hero who is not actually good at cooking but can simply order sauces from a Japanese online supermarket.

There is also a thread of celebrating mundane chores and feminine crafts, especially ones that may be felt by the implied reader to be often overlooked. The roots of this reach back to the way fairy tales so often reward and make magical household tasks, as girls cook and clean their way to being the heroine of the story. Sophie in Howl’s Moving Castle and Chihiro in Spirited Away are both iconic for their heroic efforts of cleaning. Birthday Wonderland even has a knitting competition. Baking cakes, crochet flowers and making homemade shampoo bring the heroine of Ascendance of a Bookworm universal praise, but it takes her a while to realise the full worth of her modern knowledge and many of the early arcs are devoted to her learning and negotiating her own worth in a world that is keen to exploit her.

For the other world to act as an allegory for the character, externalising their personal struggles, it often visually or thematically mirrors the real one. The lessons learnt are real and persist even if the worlds themselves do not. In the recent live-action Nutcracker and Four Realms (2018, pictured), Clara repeatedly expresses her need to return home lest her family worry about her disappearance and is reassured by the Sugarplum Fairy that time works differently in the Four Realms. Clara had recently lost her mother and her journey through the Four Realms becomes one of confronting loss as it too is in mourning for her mother, their creator. In Spirited Away, the world of Yubaba’s bathhouse is at first mistaken for an abandoned and bankrupt theme park by Chihiro’s parents, as they stumble upon it whilst moving across the country. Chihiro’s own discomfort over being uprooted from her home by her parents plays out in the spirit world. Birthday Wonderland’s listless Akane struggles with her own confidence as she steps into the role of becoming Wonderland’s chosen one.

In fantasy movies, it is also not uncommon for actors to double up, cast in parallel roles in the fantasy land, underscoring how it acts as an exaggerated or dream version of our own world. The Wizard of Oz memorably does so with Dorothy’s companions also playing her Kansas farmhands. Return to Oz (1985, pictured) has much of the hospital staff also play the villains of Oz and the patients double up as the heroes and Dorothy’s allies. Hospital gurneys and electroshock machines all return in Oz as nightmarish monsters. Labyrinth features a long pan of Sarah’s room all the various books and toys that might be said to have inspired the titular goblin realm. Blink and you might miss a brief glimpse of a photo of Sarah’s dead mother with her real-world boyfriend, played by David Bowie.

Interweaving wonderlands with the real world in this way makes them densely beautiful as metaphors but limits their ability to be their own separate, believable realities. The lessons they teach may be life-changing, but often they stop existing for the reader when the protagonist leaves.

But the removal of the Return breaks this allegory. The emergent trend in Japanese portal fantasy to ignore the Return frees the story to become a power trip, a deep dive into world building, a cheap gimmick to shortcut empathy or even a thought experiment built around identity. The artificiality of game-worlds is deconstructed and interrogated (So I’m a Spider, So What? (below) does this, but so does Yahtzee Crowshaw’s Mogworld in English). Portal fantasies drag their protagonists into visual novels and dating sims in order to shatter predestined paths and stock characters. I’m in Love with the Villainess revels in this as the heroine is besotted not with any of the gamified “capture targets” of a dating sim, but the cruel and petty villainess who bullies her.

The protagonist’s Earth origins can be used to bestow them with knowledge and motivations outside of their new world’s norm, much as the fundamental spirit of Black Adder was that of a cynic from our own time, archly commenting on the foibles of the past. Ascendance of a Bookworm’s author confessed that she hadn’t planned to write a portal fantasy, but when plotting her printing revolution in a medieval fantasy world, it was simply easier to have her character be motivated by memories of libraries in our world and be already familiar the principles of printing. It not only justifies the knowledge but the stubborn proactivity of the protagonist.

This need to return in Portal Fantasy has been repeatedly interrogated by writers, especially as a new renaissance of portal fantasy is underway in English. Most notable is Seanan McGuire’s Wayward Children series, concerned as it is with what happens after the Return. Eleanor West’s Home for Wayward Children is a boarding school set up as a refuge for those who have returned from fantasy lands but cannot acclimatise themselves to the mundane world. Central to Every Heart a Doorway, the first volume, is the soul-consuming yearning to find again the portal that would take them back to where they truly belonged.

A lot of traditional Anglophone portal fantasy is built around the Return because it is about the childish things we away for adulthood. Growing up, to paraphrase Steven Spielberg’s Hook, is an awfully big adventure. But we are no longer in the economic resurgence that lifted up the baby boomers. We aren’t even in the 1990s, which was when Spielberg made Hook. Times have changed. A lot of ink has been spilled on the economic powerlessness of the modern adult and how we are also far more mired in childish things. A lot of us grew up asking how anyone could give up those glimpses of wonder and fantasy, especially in contrast to the world that we have found ourselves inheriting. Perhaps that is why we are seeing a resurgence of portal fantasy in English and why it has crushed almost every other genre in the sphere of Japanese light novels. Much like Sarah at the end of Labyrinth, we simply still have need for them, even as adults.

Jeannette Ng is the author of Under the Pendulum Sun.

Leave a Reply