Planetes

December 6, 2020 · 0 comments

By Andrew Osmond.

Planetes is an anime space series that doesn’t have any giant robot suits. Nor does it have any aliens, androids, cyborgs, terraforming, telepathy, black holes, interplanetary empires, galaxy-spanning travel, chatty computers, cloning, time travel or freakishly gifted adolescents.

Planetes is an anime space series that doesn’t have any giant robot suits. Nor does it have any aliens, androids, cyborgs, terraforming, telepathy, black holes, interplanetary empires, galaxy-spanning travel, chatty computers, cloning, time travel or freakishly gifted adolescents.

Planetes is also widely hailed as one of the best science-fiction anime ever made, winning Japan’s prestigious Seiun SF award for Best Dramatic Presentation in 2005. The source Planetes manga by Makoto Yukimura had already won the Seiun’s comics prize three years earlier, making it a rare case of the same story winning Japan’s top prize in two different media. In both manga and anime form, Planetes can be described as “hard SF” – that is, science-fiction that’s rigorously grounded in real science or carefully extrapolated from it.

The hard SF label can have misleading connotations, suggesting something cold and clinical like 2001: A Space Odyssey. That image was busted in the 2010s by recent, rousing hard SF films like Gravity and The Martian (and perhaps Interstellar, though its “hard” credentials are debatable). But all these films were made years after Planetes, which is an immensely human, humorous series that just works very hard at making its fictional future plausible.

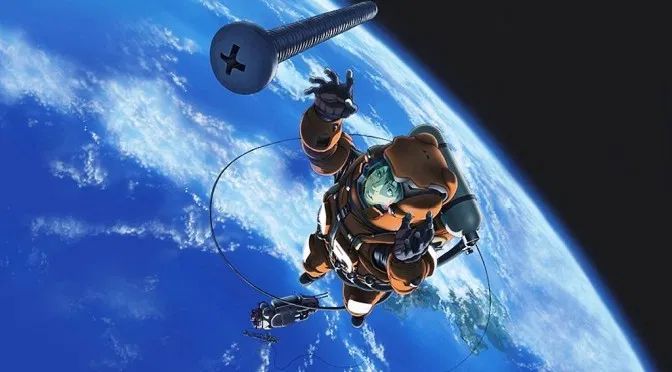

It’s set in 2075, when space exploration has developed greatly, but not miraculously. True, far more people live and work in space than in our time. Space stations are larger and accessible to civilians, even children with parents, once they can get used to floating in low or zero gravity. The floating is lovingly depicted by the animators; the movement feels more buoyant than a swimming show like Free! There are moon settlements; the biggest lunar city is home to 120,000 people, while helium-3 is mined from the moon to address Earth’s energy issues (the same job that Sam Rockwell has in the film Moon).

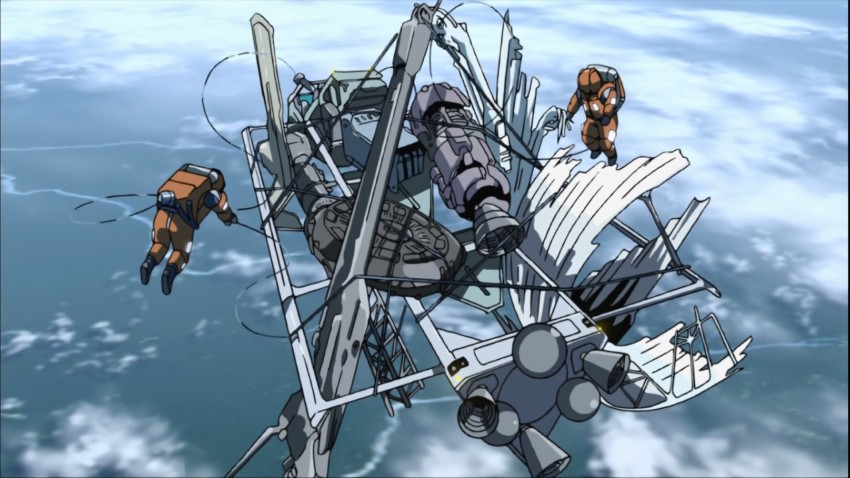

But humans have hardly conquered space, which is still an immensely hazardous frontier. One daily danger is the man-made debris left by previous human explorers. As anyone who’s seen Gravity will know, space debris doesn’t float harmlessly where it was left; it orbits Earth at great speed. Like Gravity, Planetes invokes the Kessler Syndrome, a theory that suggests that as more man-made objects are fired into orbit, eventually they will trigger lethal chain reactions. Colliding debris creates more debris, creating still more collisions.

Planetes focuses on a team of people whose job is to find and dispose of this debris – literally the garbage duty of space. Most of them are unexceptional, at least in terms of qualifications, while their place on the company ladder couldn’t be lower. When the viewpoint character Ai Tanabe, a 20 year-old college grad arriving in space for the first time, tries to find the “Debris Section,” she initially comes to a control room, which is all huge screens and glowing maps of the world. She introduces herself enthusiastically… only to be scolded for being in the wrong place and sent on a lift to the bottom of the station. SF comedy fans may look for a “Beware of the Leopard” sign, though I didn’t see one.

Planetes focuses on a team of people whose job is to find and dispose of this debris – literally the garbage duty of space. Most of them are unexceptional, at least in terms of qualifications, while their place on the company ladder couldn’t be lower. When the viewpoint character Ai Tanabe, a 20 year-old college grad arriving in space for the first time, tries to find the “Debris Section,” she initially comes to a control room, which is all huge screens and glowing maps of the world. She introduces herself enthusiastically… only to be scolded for being in the wrong place and sent on a lift to the bottom of the station. SF comedy fans may look for a “Beware of the Leopard” sign, though I didn’t see one.

Here, Ai finally finds the cramped, dirt-stained Debris Section, mockingly nicknamed the “Half Section” as it has only half the staff that it needs. There’s Lavie, a ridiculously servile company man desperate to please his bosses – he’s also a hammy magician, a fact completely ignored by everyone else. Philippe is an affable, middle-aged marshmallow. Among the more skilled professionals, Yuri is a handsome, kindly Russian man; any suspicion that he might be a potential romantic interest is dispelled by tragic later revelations.

Then there are two women, Rivera, a stone-faced intern who we get to know much later in the series and Fee, a chain-smoking woman pilot. Yes, space workers smoke in Planetes, though in strictly limited enclosed zones, analogous to the designated smoking areas in Tokyo. This may be one of Planetes’ less likely details, given how precious oxygen is in space, but this is a Japanese show; smoking is declining in Japan, but it’s still dying terribly hard.

The Debris section also includes Hoshino, who’s the show’s other main character together with Tanabe. Though he’s about the same age, Hoshino is much more experienced, and very unwilling to suffer accident-prone rookies. That’s especially true when that rookie is Tanabe, who can bang on unblushingly about the power of love as if she’s a New Age therapist or an anime schoolgirl. Tanabe is voiced in Japanese by Yuki Inoue (aka Satsuki Yukino), who’s also Milly in Trigun and Kaname in Full Metal Panic! Hoshino is voiced in Japanese by Kazunari Tanaka, who sadly died in 2016, aged 49.

Despite Tanabe’s idealism, the future in Planetes is not some Star Trek utopia. The inequalities and injustices of the present all remain. Some countries are rich, others poor; millions of people still starve, and the poorest countries are riven by “conventional” wars that leave their people in deeper misery. One series character turns out to have a horrific backstory, involving sexual exploitation. Space flight is political, bound up with global capitalism and hierarchy, a theme which comes to the fore in the series.

But not at first. One big mistake you can easily make with Planetes, especially from its early episodes, is that it’s a dramatically light, cosy comedy about cute characters learning to rub along. And indeed, that’s how many of its early episodes come over, even with all the wonderful worldbuilding. There’s a lot of very broad comedy, starting from Tanabe’s first meeting with Hoshino, who’s casually stripping off his spacesuit at the time.

But not at first. One big mistake you can easily make with Planetes, especially from its early episodes, is that it’s a dramatically light, cosy comedy about cute characters learning to rub along. And indeed, that’s how many of its early episodes come over, even with all the wonderful worldbuilding. There’s a lot of very broad comedy, starting from Tanabe’s first meeting with Hoshino, who’s casually stripping off his spacesuit at the time.

Of course, as any space buff knows, astronauts wear “Maximum Absorbency Garments” during space operations, which is another way to say that they wear diapers. However, Tanabe is so green that she doesn’t realise this until Hoshino’s, ahem, absorbency garment is staring her in the face. It’s a very funny alternative to the zillions of female underwear “jokes” which infest anime, and it’s also grounded in reality.

The same goes for many of Planetes’ early episodes. One especially silly story, for example, has Hoshino and Tanabe visiting the moon city and encountering a tribe of mad ninja movie fans who chase them while performing preposterous stunts… except that these stunts aren’t so preposterous in lunar gravity. Another story has the Debris team hounded by whole armies of lawyers, who are hellbent on selling them life insurance… insurance that the characters certainly need, given the deadly hazards of their work.

Another early episode might have been inspired by the anime of Satoshi Kon. It’s a screwball comedy about various parties chasing each other round a spaceship, including a pickpocket, a band of filmmakers illegally shooting a horror flick (in space, guerrilla film-making lives on!), and a family with a little girl. Except that the family are running away from loan sharks, and the despairing parents are actually planning to kill their child in a group suicide, giving the farce a very dark edge.

And then Planetes starts to change. It would be facile to say that it gets “dark,” but it does start to get deep, and by the later episodes it’s turned into an incredibly intense, audacious drama on both human and SF levels. One of the last episodes has a cliff-hanger that’s viscerally terrifying; it also threatens to annihilate the moral identities of contrasting characters whom we’ve come to care for greatly.

Many anime series deepen dramatically over their run – try comparing the early and late episodes of Fullmetal Alchemist. But Planetes is an exceptional triumph of serial story engineering, in ways you only appreciate by re-watching the early episodes and seeing how much was seeded from the start. One of the show’s few big missteps is its peppily cheery closing theme song, “Wonderful Life,” which fits the show at first but feels wildly mismatched when things deepen later on. However, the opening song, “Dive in the Sky”, is majestically perfect; both were performed by singer-songwriter Mikio Sakai.

I won’t spoil much about the later Planetes episodes, but they’re especially concerned with the ethics of the space programme. On the one hand, it’s easy to dress up space exploration rhetorically (in much classic sci-fi, for example) as an inherently good, heroic endeavour; as an inevitability of evolution; and as a triumph of the human will. But if that last phrase gives you pause, then Planetes gives a lot of time to the counter-case.

I won’t spoil much about the later Planetes episodes, but they’re especially concerned with the ethics of the space programme. On the one hand, it’s easy to dress up space exploration rhetorically (in much classic sci-fi, for example) as an inherently good, heroic endeavour; as an inevitability of evolution; and as a triumph of the human will. But if that last phrase gives you pause, then Planetes gives a lot of time to the counter-case.

Much of the later series revolves around a new, hugely ambitious spacecraft called the Von Braun – and if that name seems too on-the-nose, remember there’s already a moon crater named after him. For readers who don’t know, Von Braun was a historical German aeronautics pioneer, a leading icon of the American space programme. That, though, was the second phase of Von Braun’s career. In the first, he was a card-carrying Nazi who helped design the V-2 rocket which killed thousands in London and across Europe. The glorious heritage of rocket science!

Planetes advances rival perspectives on space travel, via Hoshino and Tanabe. Tanabe, as we’ve mentioned, is the romantic, the idealist; or if you prefer, she’s the soppy fool. She thinks space travel is worthless unless it’s imbued with the finest human values and feeling, primarily love. Hoshino is the rationalist, the realist; or you might think that he’s a juvenile nihilist. For him, space is cold and cruel and cares nothing for “humanity”; therefore the best explorers must be unsentimental and ruthless to survive. It’s a perspective that goes back before space travel; the iconic SF story is Tom Godwin’s 1954 “The Cold Equations,” spoofed in an episode of the anime Nadesico.

Actually, the conflicting views of Hoshino and Tanabe, and the drama that results, recall a much older space series, though some SF fans, especially the “hard” ones, would argue it was really a fantasy. I’m talking about the original 1960s Star Trek, and its endless arguments between logic, as personified by Mr Spock, and humanity, as personified by Kirk and McCoy.

Planetes also makes a fascinating contrast with a much newer screen fantasy. The Marvel film Black Panther put one empowering dream on top of another; it was a superhero film which imagined an African nation with technology far beyond the “first world.” Planetes tackles similar issues, but with the opposite premise. Impoverished nations are still marginalised in the Planetes world, struggling for acknowledgement by the richer powers. In a fictional, war-torn South American country, determined local engineers come up with their own innovations in space technology, but are treated with patronising contempt when they try selling them to the world.

It’s possible to argue that the South American characters are really stand-ins for the Japanese. Japan, after all, has its own post-war narrative of empowerment through selling technology to the world, and older viewers will remember when the Western media used “made in Japan” as a synonym for inferior goods. But in Planetes, Japan is depicted unambiguously as a first world country, as part of the elite, the club shutting out poorer countries. The geopolitics strengthen in the later episodes, which bring a South American-born woman, Claire, to prominence. That’s unusual enough for an anime, but Planetes gives Claire a journey that’s spectacularly dramatic and provocative.

Planetes was animated by the Sunrise studio, home of the Gundam franchise, which combined giant robot fantasies with real SF from the 1970s. Gundam may well have influenced the sympathetic adversaries who emerge in Planetes’ second half. It may also have inspired the show’s climax, which involves a crisis that’ll look familiar to Gundam fans. But Planetes doesn’t just look back to Sunrise’s past glories. The Planetes staff includes a stand-out duo, director Goro Taniguchi and writer Ichiro Okouchi. They would soon pair up again, on a little Sunrise show called Code Geass.

Planetes was animated by the Sunrise studio, home of the Gundam franchise, which combined giant robot fantasies with real SF from the 1970s. Gundam may well have influenced the sympathetic adversaries who emerge in Planetes’ second half. It may also have inspired the show’s climax, which involves a crisis that’ll look familiar to Gundam fans. But Planetes doesn’t just look back to Sunrise’s past glories. The Planetes staff includes a stand-out duo, director Goro Taniguchi and writer Ichiro Okouchi. They would soon pair up again, on a little Sunrise show called Code Geass.

Beyond Sunrise, another Planetes precursor is Gainax’s anime film The Wings of Honneamise, which reimagines the space race on an imaginary world. Like Planetes, Honneamise has characters working in low-status, low-esteem jobs, who might reasonably wonder what’s the point of their work, and a male protagonist wondering what’s the point of his life. Notoriously, Honneamise had a scene of sexual violence that many viewers find indefensible. In Planetes… well, let’s just say more than one woman show their teeth when men force themselves on them. We’re a long way from Captain Kirk.

Planetes also compares to the Patlabor anime franchise of the 1990s, about a police team made up of consummately ordinary working people with believable lives and relationships, even if they do pilot giant robot suits. Like Patlabor, Planetes includes stabs at big business and corporate culture, including a story reveal that an apparently soulless bureaucrat used to be a Steve Jobs-style techno-maverick. You can also link Planetes to the “workplace anime” shows that are flourishing now, set in today’s Japan; for example Sakura Quest, about characters struggling to promote a rural village, or Shirobako, about the people who make anime itself.

Planetes’ SF realism, though, has remained pretty much a one-off in anime, even seventeen years after it was released to thunderous acclaim. Perhaps films like Gravity and The Martian will finally tempt someone else to do something similar. Come to think of it, there’s a prominent anime director who does have a clear interest in space. He came to fame with a fantasy about alien wars and interstellar text messages, but his film 5 Centimeters per Second, was more grounded; it’s partly set around Japan’s real Tanegashima Space Centre, where wide-eyed youngsters watch rockets launch into infinity. He also made a film that hinged on hazardous real objects lurking in space. So, who’s rooting for Makoto Shinkai’s Planetes?

Andrew Osmond is the author of 100 Animated Feature Films. Planetes is released in the UK by Anime Limited.

Leave a Reply