Books: The Atomic Bomb in Japanese Cinema

November 4, 2015 · 0 comments

By Jasper Sharp.

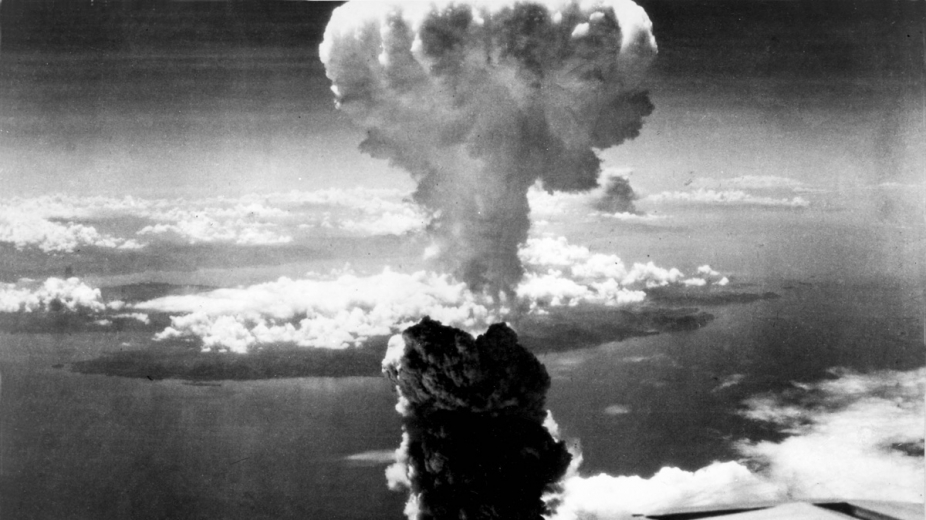

This year marks the 70th anniversary of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki that brought about Japan’s surrender and an end to World War II. The period between the two dates of the blasts, on the 6th August and 15th August respectively, saw the usual intense focus in the international media, reminding us all temporarily of the full horror of nuclear war and why such events must never happen again.

This year marks the 70th anniversary of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki that brought about Japan’s surrender and an end to World War II. The period between the two dates of the blasts, on the 6th August and 15th August respectively, saw the usual intense focus in the international media, reminding us all temporarily of the full horror of nuclear war and why such events must never happen again.

The vast majority of us for whom Hiroshima and Nagasaki are just distant events, both in terms of time and geography, find it nigh-on impossible to imagine exactly what it must have been like to have been caught anywhere near the blasts. The sad reality is that, anniversaries being what they are, while many of the surviving victims are brought out every decade to unburden themselves and relive their traumas through their testimonies and recollections, we won’t see a similar focused period of debate and discussion until 2025. By this time, there will be even fewer survivors, if any at all – personal memory will have disappeared leaving only historical memory, as represented, for example, on film.

The publication of Matthew Edwards’ anthology The Atomic Bomb in Japanese Cinema: Critical Essays is therefore timely – in the UK at least, the mainstream news has already long moved on to other topics. Already this year’s commemorations seemed relatively muted in comparison with previous anniversaries, such as 1995, which saw the release of the Japanese-Canadian co-production Hiroshima (directed by Roger Spottiswoode, interviewed about the project in this book, and Koreyoshi Kurahara), a reconstruction using archive footage, eyewitness accounts and dramatic sequences of the decision making process that led to America’s decision to unleash the devastating power of the A-bomb for the first time in history. On 5th August 2005, the BBC broadcast a new docudrama, also called Hiroshima, directed by Paul Wilmshurst, while the UK saw the long-overdue release of the anime Barefoot Gen (Hadashi no Gen, 1983), directed by Masaki Mori, and its sequel Barefoot Gen 2 (Hadashi no gen 2, 1986), directed by Hirata Toshio, both based on the manga of the same name by Keiji Nakazawa (who was only six years old when the bomb fell on his hometown of Hiroshima), first serialized in Japan in Shonen Jump in 1973.

Alongside issues of the timings of such releases, we might also want to consider how time is represented within the films themselves. Perhaps ironically, given its cartoon format, there are few depictions of the bombing quite as powerful as that of Barefoot Gen. An oppressive air of anticipation lingers over its first half hour, which unfolds almost whimsically as a series of vignettes about the hardships of family life during the waning days of the war. Then, as the dark shadow of the Enola Gay crawls sluggishly over the horizon signalling the final moments of calm before the storm, we see a trail of ants crawling prophetically into Gen’s house. As the bomb detonates, Gen is caught frozen in the act of picking up a stone from the street outside. The split second in which it first became apparent that humans had the destructive power to wipe themselves out at the press of a button during that frozen moment of 8.15am on 6th August 1945 is magnified to chilling effect.

Alongside issues of the timings of such releases, we might also want to consider how time is represented within the films themselves. Perhaps ironically, given its cartoon format, there are few depictions of the bombing quite as powerful as that of Barefoot Gen. An oppressive air of anticipation lingers over its first half hour, which unfolds almost whimsically as a series of vignettes about the hardships of family life during the waning days of the war. Then, as the dark shadow of the Enola Gay crawls sluggishly over the horizon signalling the final moments of calm before the storm, we see a trail of ants crawling prophetically into Gen’s house. As the bomb detonates, Gen is caught frozen in the act of picking up a stone from the street outside. The split second in which it first became apparent that humans had the destructive power to wipe themselves out at the press of a button during that frozen moment of 8.15am on 6th August 1945 is magnified to chilling effect.

As Ian and Dominic Higgins, the British directors of All That Remains, a feature-length animation/live action hybrid currently still in production based on the life of Nagasaki bomb survivor Takashi Nagai (author of such well-known books in Japan as The Bells of Nagasaki [1946] and himself the subject of two previous Japanese films, Hideo Oba’s The Bells of Nagasaki from 1950 and Keisuke Kinoshita’s Children of Nagasaki from 1983) tell Matthew Edwards, the editor and main contributor to The Atomic Bomb in Japanese Cinema, “One of the most powerful scenes of an atomic bombing can be seen in Barefoot Gen, the 1983 animated version. It was nightmarish and surreal – and yet far more vivid and real than any other depiction we had seen. The film became a big influence on us.”

One of the main strengths of the book is that it covers such a wide spectrum of films, both Japanese and foreign, about the bombing. The sheer number of Japanese titles in the filmography at the end should help dispel the notion that the Japanese are themselves uncomfortable talking about the A-bombings, and that films about Hiroshima and Nagasaki are rare.

The timeline of such releases is indeed fascinating – the various treatments over the years have been influenced by a combination of such factors as censorship (between 1946-52, the Allied Occupation suppressed criticism of the bombings by the Japanese), the declassification of secret information, political sensitivities, revelations about the long-term effects of radiation sickness on the hibakusha survivors and the global geopolitical climate, particularly during the Cold War climax of the 1980s.

What also comes across is how filmmakers have wrestled with the technological constraints of conveying in cinema the scale of the devastation wrought by the bomb and the psychological scars of those who witnessed it. Particularly interesting in this regard is Johannes Schonherr’s interview with Go Shibata, a young director born in 1975 with no direct experience of the bombings but who nonetheless, like all Japanese, has grown up under its shadow.

In 1999, Shibata realised the relatively obscure but immensely potent 16mm indie production NN-891102 (pictured) as his graduation project from the Osaka University of Arts. The cryptic title again highlights the criticality of the date and time of this historical and personal turning point (it is an acronym of “Nagasaki Nuclear 8 [August] 9 [the day] 11:02 [the time]”), while the content takes an innovative approach to conveying how the shock of the blast imprinted itself in the nervous systems of its survivors sonically, by depicting a 5-year-old boy who survives the fateful blast and thinks that its sound has been captured on his father’s tape recorder, only to spend the rest of his life obsessively attempting to reproduce it when the tape appears empty.

In 1999, Shibata realised the relatively obscure but immensely potent 16mm indie production NN-891102 (pictured) as his graduation project from the Osaka University of Arts. The cryptic title again highlights the criticality of the date and time of this historical and personal turning point (it is an acronym of “Nagasaki Nuclear 8 [August] 9 [the day] 11:02 [the time]”), while the content takes an innovative approach to conveying how the shock of the blast imprinted itself in the nervous systems of its survivors sonically, by depicting a 5-year-old boy who survives the fateful blast and thinks that its sound has been captured on his father’s tape recorder, only to spend the rest of his life obsessively attempting to reproduce it when the tape appears empty.

There are a lot of films detailed in the 21 essays contained within the 288 pages of this well-meaning and often informative work, although whether one can describe “genbakudan cinema” as a genre, as Edwards does, is a moot point. One could probably talk of a genre of writing tackling the subject though: this latest anthology follows in the wake of, among others, Nuclear War Films (ed. Jack Shaheen, 1978); The Japan/America Film Wars: WWII Propaganda and Its Cultural Contents (eds. Abé Mark Nornes and Yukio Fukushima, 1994); Hibakusha Cinema: Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and the Nuclear Image in Japanese Film (edited by Mick Broderick, 1996); Atomic Bomb Cinema: The Apocalyptic Imagination on Film (Jerome Shapiro, 2002); Atomic Light (Shadow Optics) (Akira Mizuta Lippit, 2005) and Deleuze, Japanese Cinema, and the Atom Bomb: The Spectre of Impossibility (David Deamer, 2014), as well as numerous journal and magazine articles.

Most of the above are academic works, and carry hefty academic price tags to match that will place them beyond the reach of casual readers without access to university libraries. The Atomic Bomb in Japanese Cinema is not an academic book, although it often aspires to be, and falls within McFarland’s usual tactic of pricing it accordingly, as previously noted in this review of Chinese Animation: A History and Filmography 1922-2012. While one remains impressed with the scope of the project, there are a discomforting amount of typos and factual errors that should have been caught by more rigorous peer-reviewing and editing on the side of the publishers. Another downside is that a good proportion of the writing is by non-academics or early career researchers who struggle with the critical vocabulary to put the works discussed into the necessary context or perspective.

Alarm bells immediately go off upon reading such comments as “in a country whose national cinema deals with controversial topics such as rape and violence with misogynist glee” in Edwards’ introduction. This is simply untrue of the vast bulk of Japanese cinema’s output, and yet is a sentiment echoed in Julia Alekseyeva’s chapter ‘Nuclear Skin: Hiroshima and the Critique of Embodiment in Affairs within Walls’ exploring the use of atomic imagery in Koji Wakamatsu’s rather atypical 1965 pinku eiga, which concludes with the author claiming that “in Pink film especially, the gendering of formal elements of the genre remain grossly understudied”, apparently unaware of Donald Richie’s article ‘Sex and Sexism in the Eroduction’ from as far back as 1973, and my own book on the subject Behind the Pink Curtain (2008), which devotes at least a chapter (and an associated bibliography of other research) to this issue.

Being unaware of previous research is one thing, but in other cases it is clear the writers in question haven’t seen the titles they are writing about. It is certainly worth drawing attention to the standout scene in Hiroshi Shimizu’s Children of the Beehive (1948, pictured), the earliest sequence in a fictional feature film to depict the ravaged landscape of Hiroshima, but to claim this crucial plot point is “without any dramatic dialogue or dramatic narrative purpose” flies in the face of what actually happens onscreen.

Being unaware of previous research is one thing, but in other cases it is clear the writers in question haven’t seen the titles they are writing about. It is certainly worth drawing attention to the standout scene in Hiroshi Shimizu’s Children of the Beehive (1948, pictured), the earliest sequence in a fictional feature film to depict the ravaged landscape of Hiroshima, but to claim this crucial plot point is “without any dramatic dialogue or dramatic narrative purpose” flies in the face of what actually happens onscreen.

Elsewhere The Face of Jizo (2004), Kuroki Kazuo’s rather harrowing adaptation of the stage play Chichi to Kuraseba (Living with my Father), is described by Yoshiko Fukushima as a “comedy film”, and its two-handed dramatic structure, in which Rie Miyazawa spends four days in intimate conversations with her father whom is revealed to be the phantom of her imagination after dying in the bomb blast, is described as “a familiar motif in Hollywood since the 1968 horror film Night of the Living Dead.” Tienfo Ho’s ‘Trauma and Witness in Hideo Nakata’s Ring’ presents a particularly tenuous piece of clutching at straws (or maybe cherry blossoms) in its attempt to invoke the circular imagery within the film as “a direct reference to Zen Buddhism” – for all we know, without any citation from Nakata himself, he might have been just as inspired by the tondo circular paintings found in European religious art since prior to the Renaissance.

The quality varies wildly, however, and fortunately there some real standout chapters. Yuki Miyamoto’s ‘Inconceivable Anxiety: Representation, Disease and Discrimination in Atomic-Bomb Films’ examines “representations of bodies injured or made ill by radiation”, (predominantly female ones, as the author points out), drawing comparisons between the depiction of the slow decline and death of the hibakusha heroine of Shohei Imamura’s Black Rain (1989) to the “romantic agony” of tuberculosis victims in mid-eighteenth century literature. In doing so, the film and others like it avoid the horrific truth of radiation sickness and prejudice against hibakusha and “shift the focus from the violence of the atomic bombings to the sadness of a woman with a social stigma who can’t find her romantic partner… a stigma perpetuated, rather than undermined, in the movie’s romantic tropes.”

Another invaluable essay is Mick Broderick and Junko Hatori’s ‘Pica-don: Japanese and American Reception and Promotion of Hideo Sekigawa’s Hiroshima’, detailing the production and censorship circumstances surrounding a 1953 film that is barely remembered today, but which was commissioned by the Japan Teachers’ Union in response to the poor domestic critical reception of Kaneto Shindo’s far better-known Children of Hiroshima (1952), which competed at Cannes in 1953.

Another invaluable essay is Mick Broderick and Junko Hatori’s ‘Pica-don: Japanese and American Reception and Promotion of Hideo Sekigawa’s Hiroshima’, detailing the production and censorship circumstances surrounding a 1953 film that is barely remembered today, but which was commissioned by the Japan Teachers’ Union in response to the poor domestic critical reception of Kaneto Shindo’s far better-known Children of Hiroshima (1952), which competed at Cannes in 1953.

It is with such chapters that the book really shows its value. While we might baulk that there are certain titles omitted from its wider survey of films about the bomb, there are also plenty of relatively unknown titles that do get their dues, and the discourses surrounding many of these, as well as the interviews with their makers, are at times really enlightening.

This is never less so than in Edwards’ interview with the Japanese-American documentary maker Steven Okazaki, who has returned to the subject on several occasions and from different angles with Survivors (1982), The Mushroom Club (1985) and White Light/Black Rain: The Destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki (2007). The early scenes of this final title, in which a number of Junior High school kids fail to recognize the significance of the date 6th August 1945, highlights the real necessity of more films and books on this darkest point in mankind’s history to keep the issue of what happened another lifetime ago from fading from the public eye.

Jasper Sharp is the author of A Historical Dictionary of Japanese Cinema.

anime, atomic bomb, Barefoot Gen, books, film, Hiroshima, Japan, Jasper Sharp, manga, Nagasaki

Leave a Reply