Shinoda’s Silence

December 11, 2016 · 0 comments

By Jasper Sharp.

It has been several decades since Martin Scorsese first professed a desire to film Silence (Chinmoku), Shusaku Endo’s Tanizaki Prize-winning 1966 novel about the persecution of “hidden Christians” (kakure kirishitan) in 17th-century Japan. The story follows the Portuguese Jesuit missionary, Padre Rodrigues, after he is dispatched eastwards from Macao, arriving in 1639 on Japan’s craggy shoreline with his companion Garrpe to search for his predecessor, Padre Ferreira, who disappeared some 20 years previously and is rumoured to have gone native. It is not long before Rodrigues’ own spiritual convictions are put to the test, when their presence amongst the clandestine enclave of Japanese Christians who harbor them in their impoverished rural village is noted by the region’s ruthless overlord Inoue, who sets about trying to torture this ideological interloper into renouncing his faith.

It has been several decades since Martin Scorsese first professed a desire to film Silence (Chinmoku), Shusaku Endo’s Tanizaki Prize-winning 1966 novel about the persecution of “hidden Christians” (kakure kirishitan) in 17th-century Japan. The story follows the Portuguese Jesuit missionary, Padre Rodrigues, after he is dispatched eastwards from Macao, arriving in 1639 on Japan’s craggy shoreline with his companion Garrpe to search for his predecessor, Padre Ferreira, who disappeared some 20 years previously and is rumoured to have gone native. It is not long before Rodrigues’ own spiritual convictions are put to the test, when their presence amongst the clandestine enclave of Japanese Christians who harbor them in their impoverished rural village is noted by the region’s ruthless overlord Inoue, who sets about trying to torture this ideological interloper into renouncing his faith.

With Scorsese’s long-anticipated passion project finally primed for release across the world, the time seems ripe to revisit the previous film version of the story, directed by Masahiro Shinoda and originally released in 1971. Though it played In Competition at the 1972 Cannes Film Festival, it was not until its UK DVD release on Eureka’s Masters of Cinema label in 2007, when Scorsese’s adaptation first looked like it might become an imminent reality, that Silence was finally made widely available outside of Japan.

Novelist Endo’s close involvement in the project, co-scripting alongside Shinoda, undoubtedly played a critical role in bringing the psychological dimensions of his novel to the screen with a perception and intelligence all too rare in modern cinema. That the story’s main theme of blind faith in the face of adversity still has such universal resonance is undoubtedly due to Endo’s own unusual background. Not only was he a Catholic in a country with a Christian population of less than one percent, but a second-generation one; his mother converted to the religion after divorcing and moving back to Kobe from Japan’s puppet state of Manchuria in 1933, and had him baptised when he was eleven. Endo was also one of the first Japanese students in the post-war period to study abroad, researching modern European Catholic literature at the University of Lyons.

Novelist Endo’s close involvement in the project, co-scripting alongside Shinoda, undoubtedly played a critical role in bringing the psychological dimensions of his novel to the screen with a perception and intelligence all too rare in modern cinema. That the story’s main theme of blind faith in the face of adversity still has such universal resonance is undoubtedly due to Endo’s own unusual background. Not only was he a Catholic in a country with a Christian population of less than one percent, but a second-generation one; his mother converted to the religion after divorcing and moving back to Kobe from Japan’s puppet state of Manchuria in 1933, and had him baptised when he was eleven. Endo was also one of the first Japanese students in the post-war period to study abroad, researching modern European Catholic literature at the University of Lyons.

This personal background informing Endo’s novel married well with Shinoda’s own intellectual concerns (and those of many of the New Wave filmmakers) of exploring such ideas of individual and national identity within an international context. The film opens with a montage of 17th-century woodcut prints and an accompanying narration that lays out the historical context, explaining the crisis in Catholicism within Europe that saw the establishment of the Society of Jesus (Jesuits) in Spain in 1534, and this new order’s attempt to expand their base, with the first Jesuit missionary, Francisco Xavier appearing on the southern shores of Japan in 1549 – arriving with him, the voiceover emphasizes, came the gun. Within 30 years, Japan had 200 churches, 75 priests and 300,000 believers, until the Tokugawa shogunate’s imposed its isolationist “closed country” policy of sakoku in 1635 and violently forced the imported faith underground.

With little outside influence, over the following centuries Christianity mutated and hybridized with nativist belief systems. Shinoda’s film evocatively captures the unique tones of this domesticated faith, with the interior scenes of secret worship rendered in a similar flat perspective and reddish palette as the opening woodcuts, drawing attention to such other unique elements as the use of a statue of Kannon by the worshippers as a surrogate for the Virgin Mary, and the deployment by the officials of fumie, wooden icons of Christ on which suspected believers are forced to stamp so as to renounce their faith.

Silence was shot by the legendary Kazuo Miyagawa, best known for bringing his breathtaking touch to the late-career works of Mizoguchi, as well as such other salient titles from Japan’s classical era as Akira Kurosawa’s Rashomon (1950), Yasujiro Ozu’s Floating Weeds (1959) and Kon Ichikawa’s Conflagration (1958). It was one of the first titles the veteran cinematographer worked on after spending the previous decade almost exclusively for Daiei, which had filed for bankruptcy in 1971; the following year he would shoot Baby Cart in Peril (1972), the fourth instalment in the Lone Wolf and Cub series produced by Katsu Pro, the company established by the former star of Daiei’s Zatoichi series, Shintaro Katsu. As well as going on to work on Kurosawa’s Kagemusha (1980), Miyagawa would also film the later Shinoda titles MacArthur’s Children (1984), Gonza the Spearman (1986) and, his final credit, the Japanese-German coproduction The Dancer (1989).

Despite the epic potential of the material, Miyagawa takes a low-key, almost documentary approach, filming in the muted hues of the new Fujicolor stock and adopting a tight televisual 4:3 aspect ratio. At times, his ability to manifest the sublime in the mundane, amply demonstrated in Ugetsu (1953) and Sansho the Bailiff (1954), recalls the poetic realism of The Gospel According to St. Matthew, as rendered in 1964 by Pier Paolo Pasolini. The exterior landscapes within which the Jesuits find themselves are bleak and forbidding, yet strangely beautiful and ethereal, underscoring the sense of dislocation, with the rice paddies in which the villagers toil are crowded right up against the cliffs of the coastline.

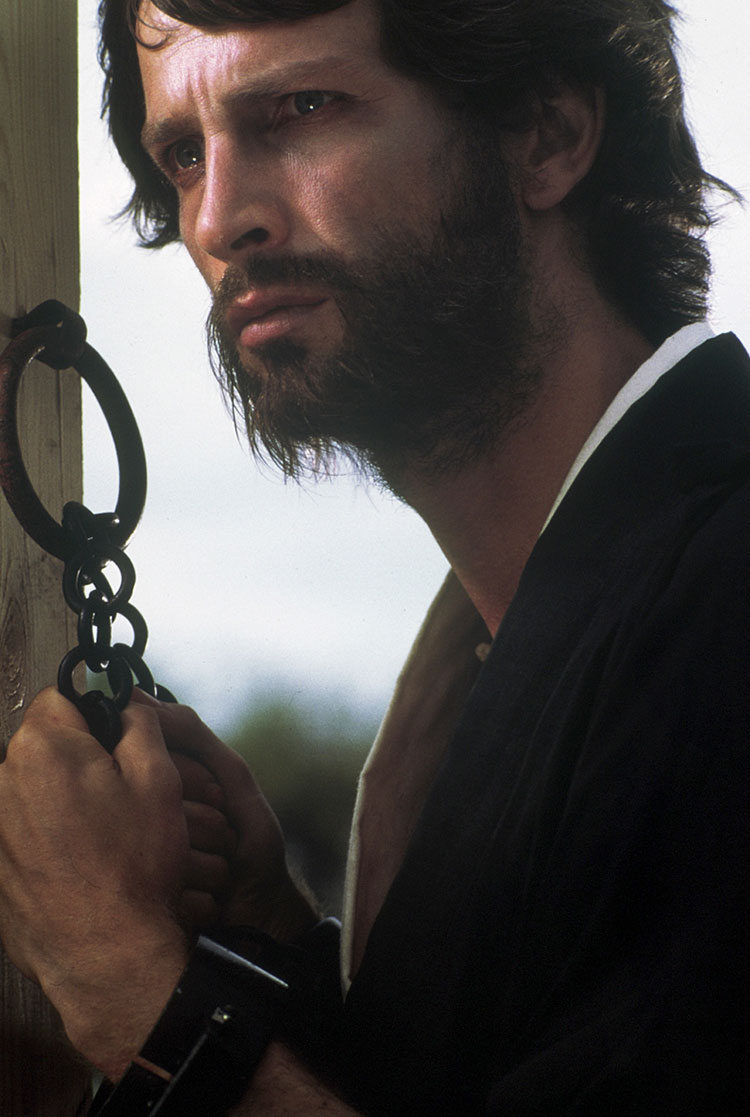

When Padre Rodrigues observes that with the heavy taxes imposed by the local magistrates, the peasants’ lives are no better than their cows or horses, it becomes clear why the authorities are so keen to clamp down on a foreign belief system that is so disruptive to the status quo. Occasionally the imagery veers towards the surreal, as in a sequence in which three of the villagers are strapped to crucifixes as the sea rises around them, to force them into confessing that they are sheltering the Portuguese. Also worthy of note, and fitting given the film’s title, is the masterful use of sound, with the crashing of waves against the shoreline and the omnipresent throb of summer cicadas periodically yielding to a score by the renowned avant-garde composer Toru Takemitsu, a regular collaborator with Shinoda and other New Wave filmmakers, notably Hiroshi Teshigahara’s films such as Woman in the Dunes (1964) and The Face of Another (1966) – a Spanish guitar melody assailed by a discordant pandemonium of traditional instrumentation to suggest the irreconcilable clash of two cultures. David Lampson does an impressive job in the Richard Chamberlain-esque central role, performing in both Japanese and English. One wonders both how he ended up cast in a Japanese film and whatever happened to him subsequently (he seemingly became a novelist, and was credited with co-creating the David Tennant pilot Rex is Not Your Lawyer), although it appears that Don Kenny, who plays Garrpe, continues to live in Japan, working as a translator and actor with a specialist interest in Kyogen theatre.

Silence is a hauntingly effective, slow-burning portrait of one man’s hubris and intransigence that raises fascinating questions as to whether one can ever successfully impose a foreign ideology on a nation and its people, most surely an area of considerable interest to the post-war generation of which both Endo (born 1923) and Shinoda (born 1931) were both a part. It remains to be seen what slant Scorsese brings to the material, but at least we already have one near-flawless adaptation, and one whose reputation can only benefit from the attention the new release will surely bring to it.

Masahiro Shinoda’s Silence is out now from Eureka on its Masters of Cinema label. Martin Scorsese’s Silence is released in the UK on New Year’s Day.

Leave a Reply