The Encyclopedia of Japanese Horror Films

September 20, 2017 · 0 comments

By Jasper Sharp.

Reference books have had to fight their corner harder than most in the internet age. For the subject of film in particular, online sources such as Wikipedia, Rotten Tomatoes or the IMDb (and dare I mention for Japanese film, Midnight Eye) allow instant access to facts or opinions about specific titles you might be looking for. But there’s the rub – how do you look for information about something you don’t know exists?

Reference books have had to fight their corner harder than most in the internet age. For the subject of film in particular, online sources such as Wikipedia, Rotten Tomatoes or the IMDb (and dare I mention for Japanese film, Midnight Eye) allow instant access to facts or opinions about specific titles you might be looking for. But there’s the rub – how do you look for information about something you don’t know exists?

In this respect alone, Salvador Murguia’s Encyclopedia of Japanese Horror Films is certainly a welcome reminder of the advantages of the printed word. Browsing through its 406 pages, you’ll find yourself coming across a host of titles you might never have heard of before, from the All Night Long rape-revenge series to Zombie Self-Defense Force by way of titles such as Teruo Ishii’s Blind Beast vs. Killer Dwarf, Godzilla-director Ishiro Honda’s manic mushroom movie Matango and Shion Sono’s Suicide Circle. The bulk of the entries are on individual films or film series, although there is also a smattering of biographies for salient directors, writers and manga artists, sub-genres such as “erotic grotesque nonsense”, and even one for the Scream Queen Filmfest Tokyo.

As the book highlights, there’s certainly a lot more to Japanese genre cinema beyond the familiar turn-of-the-century glut of J-horror offerings, although some of the titles stretch the definitions of horror: Hiroshi Matsumoto’s scattershot comedy Big Man Japan, Rintaro’s four-part video series Doomed Megalopolis, the anthology of ten Natsume Soseki short stories Ten Nights of Dreams and the Kinji Fukasaku disaster epic Virus are some of the more genre-bending inclusions.

As the book highlights, there’s certainly a lot more to Japanese genre cinema beyond the familiar turn-of-the-century glut of J-horror offerings, although some of the titles stretch the definitions of horror: Hiroshi Matsumoto’s scattershot comedy Big Man Japan, Rintaro’s four-part video series Doomed Megalopolis, the anthology of ten Natsume Soseki short stories Ten Nights of Dreams and the Kinji Fukasaku disaster epic Virus are some of the more genre-bending inclusions.

The advantage of this all-encompassing approach is that anime gets a fair look-in, with entries including the mecha TV series The Big O, the psychedelic arthouse animation Belladonna of Sadness, the Madhouse anthology Neo Tokyo, the Yoshiaki Kawajiri-directed Vampire Hunter D: Bloodlust, and bio entries on Katsuhiro Otomo and Shigeru Mizuki, creator of the massively popular GeGeGe no Kitaro manga series. Some of the more obvious titles, however, seems to have slipped through the cracks, such as Wicked City and Urotsukidoji: Legend of the Overfiend (1987-94).

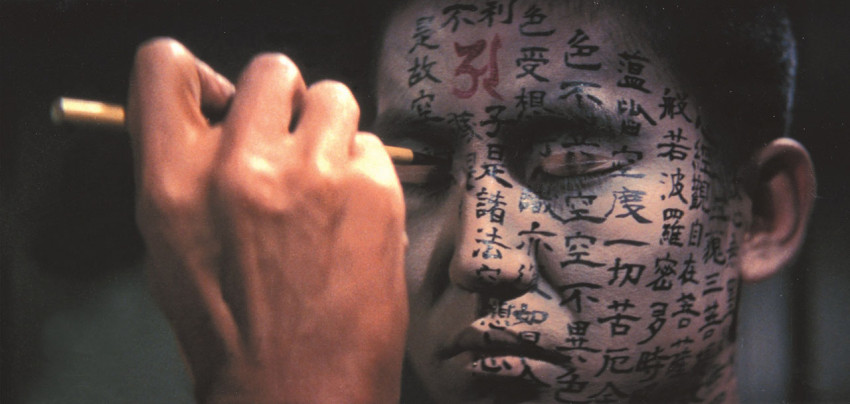

It is, of course, easy to play the “why is this included and that not?” game, but one might question why Yojiro Takita’s Heian-era fantasy Onmyoji and its 2003 sequel get separate entries while there are none for Toho’s take on The Invisible Man, Girl Divers at Spook Mansion, Ghost of the Hunchback, Goke, Body Snatcher from Hell or Wolf Guy. Why are Shinji Aoyama (who has directed only one horror, EM: Embalming) and the Roman Porno director Tasumi Kumashiro (or “porn director”, as he’s described in the text) listed while Hideo Nakata and Teruo Ishii aren’t? Why does Shiro Sano, a prolific performer who has appeared in some horror films but is hardly identified with the genre, justify one of the few entries for actors, but not the iconic Shintoho horror star of the 1950s, Shigeru Amachi?

The occasional wild cards impress. I doubt the B-movie directors Shigeru Mokudo (1901-83) or Ryohei Arai (1901-80), both responsible for a string of ghost cart movies (in the late 1930s and early 1950s respectively), have ever had such focussed attention in the English language till now. However, there is a notable imbalance towards the kind of disposable straight-to-video offerings of the past decade like Big Tits Zombie (pictured below, you’re welcome), Crazy Lips or Tokyo Gore School over older genre classics. Fun as such films may be, they are of questionable interest or historical significance. Drawing attention to lost or overlooked gems is one thing, but in the context of an encyclopaedia, it comes across more as an attempt at rewriting the canon. The immediate impression is that the book was put together by asking a wide range of contributors to write about whatever film or subject they chose rather than being assigned crucial landmarks in Japan’s horror or fantasy cinema. The result is that little sense of history or context comes across, rather like the self-published “Japanese Cinema Encyclopedia” books Thomas Weisser was bunging out in the late-1990s, although less entertaining to read.

To be blunt, the writing here is pretty dry. Each of the entries averages around 2-3 pages in length, with most of the word counts taken up by synopses. Any criticism, as such, is largely of the “say what you see” school and not a lot of the individual writers’ personalities come across. I guess this is a symptom of the way the book was conceived as part of Rowman & Littlefield’s National Cinema series. Having written The Historical Dictionary of Japanese Cinema for the same publisher, I am aware that there is a certain format and a writing style to be adhered to that downplays the voice of the author, and then there’s the difficulties in maintaining any sort of stylistic consistency when you have more than 50 contributors to deal with (although the 2+ pages describing plots for the likes of Attack Girls’ Swimteam vs. The Undead suggest the concision wasn’t high on the editorial agenda). I’m rather surprised a more structured approach to the entries wasn’t demanded, one like Sight & Sound magazine’s, for example, that separates synopses into a 100-word paragraph and leaves the rest for background information and criticism, because some of the entries make for turgid reading, as if the author in question were just trying to fill up an allotted word count.

To be blunt, the writing here is pretty dry. Each of the entries averages around 2-3 pages in length, with most of the word counts taken up by synopses. Any criticism, as such, is largely of the “say what you see” school and not a lot of the individual writers’ personalities come across. I guess this is a symptom of the way the book was conceived as part of Rowman & Littlefield’s National Cinema series. Having written The Historical Dictionary of Japanese Cinema for the same publisher, I am aware that there is a certain format and a writing style to be adhered to that downplays the voice of the author, and then there’s the difficulties in maintaining any sort of stylistic consistency when you have more than 50 contributors to deal with (although the 2+ pages describing plots for the likes of Attack Girls’ Swimteam vs. The Undead suggest the concision wasn’t high on the editorial agenda). I’m rather surprised a more structured approach to the entries wasn’t demanded, one like Sight & Sound magazine’s, for example, that separates synopses into a 100-word paragraph and leaves the rest for background information and criticism, because some of the entries make for turgid reading, as if the author in question were just trying to fill up an allotted word count.

It is a shame because I’ve worked with some of the writers before and know they’re capable of more interesting things. Some of the contributors have already published widely on Japanese horror (Jim Harper, Colette Balmain, Jay McRoy), others fall into the category of early-career researchers from a variety of academic backgrounds, eager to add something to their CVs. But make no mistake, this is not an academic book, despite the hefty cover price. Outside of the encyclopaedia entries, the two-page introduction and the contents (which also includes the Japanese text for the names of the films and directors), the most significant section of the book is the section containing the contributor biographies. There is no suggested further reading section and no in-text citations: there are short bibliographies at the end of some of the entries, though these seldom contain much beyond the name of the film and the production company.

Indeed, it sometimes feels like the author credited for each entry hasn’t even read the sources they reference. I’ll single out the section on ‘pink films’ as an offender because my Behind the Pink Curtain is listed in this entry’s bibliography. I don’t know how many times I have had emphasise, after almost ten years of researching and writing, interviewing many of the genre’s key figures in Japan and poring through original Japanese sources materials, that pinku eiga refers to INDEPENDENT films made by dedicated companies for a dedicated network of adult cinemas. This is not disputable. I can accept to some extent that the Roman Porno productions of the major studio Nikkatsu are superficially connected to the pink film in terms of contents, intent and formula, but when the author includes checklists Seijun Suzuki’s Gate of Flesh and goes on to include RoboGeisha, Helldriver and Gun Woman as recent examples of the genre, one begins to call into question the authority of not just the individual writer, but all the contributors. Pink cinema seems an odd inclusion in a book about horror in the first place, but it would have been justifiable if there were some mention of genuine pink-horror hybrids like Kinya Ogawa’s The Case of the Lusty Living Head and Ghost Story: Dismembered Phantom.

Indeed, it sometimes feels like the author credited for each entry hasn’t even read the sources they reference. I’ll single out the section on ‘pink films’ as an offender because my Behind the Pink Curtain is listed in this entry’s bibliography. I don’t know how many times I have had emphasise, after almost ten years of researching and writing, interviewing many of the genre’s key figures in Japan and poring through original Japanese sources materials, that pinku eiga refers to INDEPENDENT films made by dedicated companies for a dedicated network of adult cinemas. This is not disputable. I can accept to some extent that the Roman Porno productions of the major studio Nikkatsu are superficially connected to the pink film in terms of contents, intent and formula, but when the author includes checklists Seijun Suzuki’s Gate of Flesh and goes on to include RoboGeisha, Helldriver and Gun Woman as recent examples of the genre, one begins to call into question the authority of not just the individual writer, but all the contributors. Pink cinema seems an odd inclusion in a book about horror in the first place, but it would have been justifiable if there were some mention of genuine pink-horror hybrids like Kinya Ogawa’s The Case of the Lusty Living Head and Ghost Story: Dismembered Phantom.

A more significant omission is the complete absence of any illustrative material. Sourcing stills from the major Japanese studios can be a notoriously difficult and expensive business, but this is not necessarily the case for smaller production companies, and anyway, DVD covers and frame grabs would be permissible under the terms of “fair use” in copyright law – in short, there should be scope for some images, because without them, the book is as visually appealing as a government white paper.

Another less explicable oversight is the lack of fuller cast, crew and technical details for the individual film entries. Although some of this information can be found buried in the main descriptive/review text, you can’t just simply glance at a section beneath the entry heading to ascertain, for example, whether the film was produced for cinemas or the straight-to-cinema market, whether it is live action or animated, whether its widescreen or Academy ratio, nor who is actually in it, who produced it or who shot it. Instead, the only details given are the name of the director and the writer, the year of release, the run-time and whether the film is monochrome or in colour, and these aren’t always reliable; Kaneto Shindo’s Kuroneko (below) is stated as being 90 minutes and in colour, whereas in fact it is 95 minutes and black and white.

In the face of the relentless proliferation of online material, shortcomings such as these really highlight the necessity for a tighter editorial hand for reference books that claim to be exhaustive and authoritative. While Wikipedia might not be the most reliable of sources, it does allow for the correction of information, whereas with a book, once something is set in print it is effectively set in stone, allowing for errors to go unchallenged and perpetuated by those who cite its pages. On the evidence presented here, whether looking for information in print or online, future researchers are still going to have their work cut out for them when sorting out the wheat from the chaff.

In the face of the relentless proliferation of online material, shortcomings such as these really highlight the necessity for a tighter editorial hand for reference books that claim to be exhaustive and authoritative. While Wikipedia might not be the most reliable of sources, it does allow for the correction of information, whereas with a book, once something is set in print it is effectively set in stone, allowing for errors to go unchallenged and perpetuated by those who cite its pages. On the evidence presented here, whether looking for information in print or online, future researchers are still going to have their work cut out for them when sorting out the wheat from the chaff.

The Encyclopedia of Japanese Horror Films is available from Rowman & Littlefield.

Leave a Reply