The Witching Hour

September 30, 2016 · 0 comments

By Jasper Sharp.

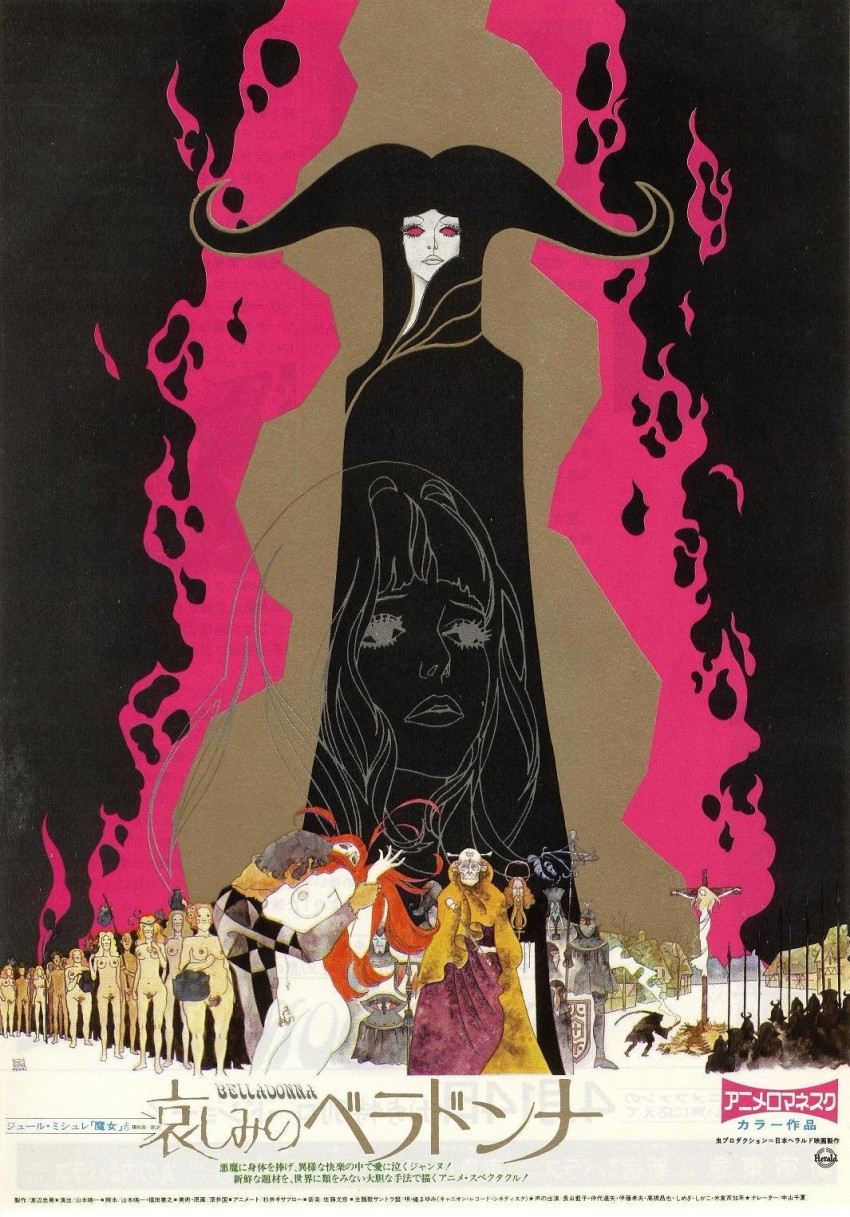

Who would have thought that one of the talking-point animated releases of the year would be an obscure title made in Japan over 40 years ago? Hailed as “One of the great lost masterpieces of Japanese animation”, Belladonna of Sadness (also known as Tragedy of Belladonna) was originally released in 1973 as the third and final of the adult-oriented Animerama series launched by Astro Boy-creator Osamu Tezuka’s Mushi Production. The trilogy, which had begun with One Thousand and One Arabian Nights (1969) and continued through Cleopatra (1970), coincided with, and indeed many would say contributed to, the company’s bankruptcy that same year.

Who would have thought that one of the talking-point animated releases of the year would be an obscure title made in Japan over 40 years ago? Hailed as “One of the great lost masterpieces of Japanese animation”, Belladonna of Sadness (also known as Tragedy of Belladonna) was originally released in 1973 as the third and final of the adult-oriented Animerama series launched by Astro Boy-creator Osamu Tezuka’s Mushi Production. The trilogy, which had begun with One Thousand and One Arabian Nights (1969) and continued through Cleopatra (1970), coincided with, and indeed many would say contributed to, the company’s bankruptcy that same year.

The film hasn’t exactly lain in limbo since then. In 1979 it was re-issued in Japan in a re-edited version and was available in the country throughout the VHS era, and a German DVD appeared from Rapid Eye Movies back in 2008. However, its eye-popping new 4K digital restoration has seen Belladonna reappraised as a cult classic, an unearthed obscurity that has gained critical traction in no lesser publications than the New York Times, albeit attracting an equal measure of controversy.

Let’s get the facile one-liner out the way: Belladonna of Sadness might be most succinctly described as an animated psychedelic porno prog-rock opera set in the Middle Ages. The inspiration is Jules Michelet’s scholarly and densely-written non-fictional work, La Sorcière, first published in 1862, a treatise on the persecution of women for witchery in medieval times by the Roman Catholic church. The book has undergone numerous reprints in the English language under the title Satanism and Witchcraft: A Study in Medieval Superstition, and was first published in a translated version in Japan under the title of Majo (“Witch”) as early as 1870.

Let’s get the facile one-liner out the way: Belladonna of Sadness might be most succinctly described as an animated psychedelic porno prog-rock opera set in the Middle Ages. The inspiration is Jules Michelet’s scholarly and densely-written non-fictional work, La Sorcière, first published in 1862, a treatise on the persecution of women for witchery in medieval times by the Roman Catholic church. The book has undergone numerous reprints in the English language under the title Satanism and Witchcraft: A Study in Medieval Superstition, and was first published in a translated version in Japan under the title of Majo (“Witch”) as early as 1870.

As Michelet writes, “For a thousand years the people had one healer and one only – the Sorceress. Emperors and kings and popes, and the richest barons, had sundry Doctors of Salerno, or Moorish and Jewish physicians; but the main body of every State, the whole world we may say, consulted no one but the Saga, the Wise Woman. If her cure failed, they abused her and called her a witch. But more generally, through a combination of respect and terror, she was spoken of as the Good Lady, or Beautiful Lady (Bella Donna), the same name as that given to fairies.”

Such source material might seem more the stuff of a Rick Wakeman concept album than a cartoon – and indeed it’s worth pointing out that those with a taste for the Hammond organ, pounding drums and funky basslines are well-served by the psychedelic free jazz score composed by Masahiko Satoh (whose other soundtracks include the 1966 pink film Season of Betrayal directed by Koji Wakamatsu collaborator Atsushi Yamatoya and a handful of late-60s Nikkatsu titles), with vocals provided by his wife Chinatsu Nakayama.

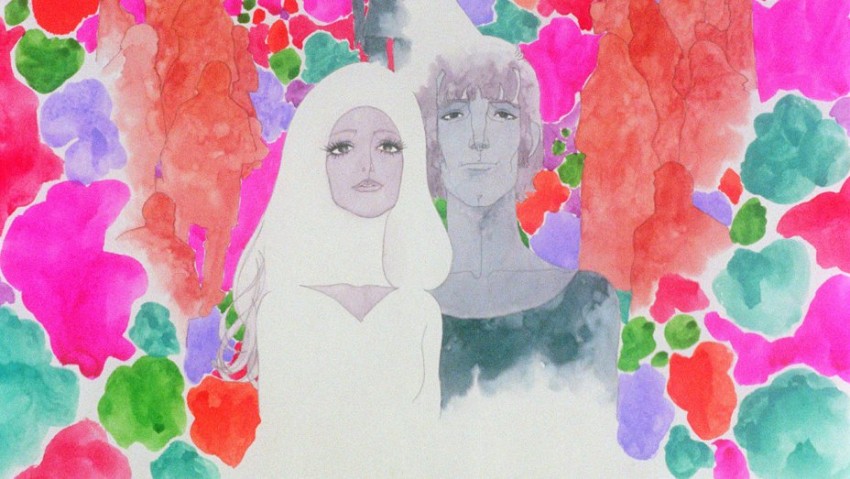

Yoshiyuki Fukuda’s script is based on one of the folktales Michelet recounts in his in his book, of two young peasants, Jean and Jeanne, whose impending wedding plans are ruined when Jeanne is violated by the feudal lord of the nearby castle. Rejected as unclean by her would-be husband, Jeanne is cajoled by a wicked willy-shaped devil (voiced by one of the country’s best-known actors, Tatsuya Nakadai) to surrender to the passions awakened within her and take revenge on her assailant.

It is a concept that could only have sprung from the anything-goes ethos of the early-1970s, and a testament to the creative aspirations of its makers to push the medium into new and uncharted waters far beyond the realms of Disney, then treading safe creative water with the likes of The Aristocrats (1971) and Robin Hood (1973). In this particular case, such aspirations would soon be crushed by harsh financial reality. By the time of its production, Mushi Production was haemorrhaging money at an alarming rate. Tezuka himself had resigned as company president in 1973, giving long-term associate Eiichi Yamamoto, who had directed episodes of the company’s seminal TV anime series of the 1960s, Astro Boy and Kimba the White Lion, free rein as director.

It is a concept that could only have sprung from the anything-goes ethos of the early-1970s, and a testament to the creative aspirations of its makers to push the medium into new and uncharted waters far beyond the realms of Disney, then treading safe creative water with the likes of The Aristocrats (1971) and Robin Hood (1973). In this particular case, such aspirations would soon be crushed by harsh financial reality. By the time of its production, Mushi Production was haemorrhaging money at an alarming rate. Tezuka himself had resigned as company president in 1973, giving long-term associate Eiichi Yamamoto, who had directed episodes of the company’s seminal TV anime series of the 1960s, Astro Boy and Kimba the White Lion, free rein as director.

The results are a Japanese animation that not only doesn’t look like anime. For the most part, it doesn’t even look like animation. Indeed, the approach goes way beyond the “limited animation” of Mushi Pro’s TV work to what anime critic Nobuyuki Tsugata described as ugokanai animation – ‘animation that is inanimate’, and which the director himself in his memoirs would later label as a ‘patchwork film’.

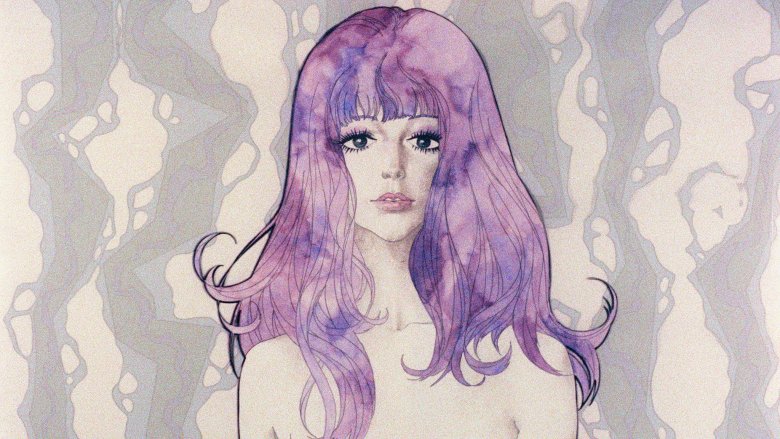

In these days of CG animation’s conformity to a standardized glossy photorealistic norm, it is no surprise that such a one-of-a-kind mash-up of styles should prove so appealing to so many modern-day viewers. Even the texture of the paper is palpable beneath the static watercolour washes of mottled mauves, ochres and slate-greys provided by the celebrated illustrator Kuni Fukai, whose luscious art design pays clear homage to modernist and Art Nouveau artists such as Gustav Klimt, Odilon Redon, Alphonse Mucha, Egon Schiele, Aubrey Beardsley and Felicien Rops.

Beyond the pans and zooms across such ornate imagery, Belladonna is hardly inanimate, throwing in techniques from Lotte Reiniger-style silhouettes, animated line sketches, and a handful of sequences rendered using the traditional cel approach, with some astonishing hypnotic segues that defy verbal description. Indeed, occasionally things teeter over into sensory overload, as style and content coalesce and Fukai’s luscious compositions of the curvaceous muse, long-lashed eyes framed by a torrent of swirling hair, morph into sensuous swelling abstractions of bulging forms and curving lines, bursting forth into violent scarlets as bodies melt and erupt in sexual jouissance.

Beyond the pans and zooms across such ornate imagery, Belladonna is hardly inanimate, throwing in techniques from Lotte Reiniger-style silhouettes, animated line sketches, and a handful of sequences rendered using the traditional cel approach, with some astonishing hypnotic segues that defy verbal description. Indeed, occasionally things teeter over into sensory overload, as style and content coalesce and Fukai’s luscious compositions of the curvaceous muse, long-lashed eyes framed by a torrent of swirling hair, morph into sensuous swelling abstractions of bulging forms and curving lines, bursting forth into violent scarlets as bodies melt and erupt in sexual jouissance.

While providing a wonderful example of how Japanese artists could pack an even more potent erotic charge when circumventing the country’s no-pubic censorship conventions, it should be pointed out that the vast variety of phallic and vaginal visual metaphors on display are often not quite as abstract as they could be. Yes, this is a pretty rude film at times, as spelled out by its reception at the Berlin International Film Festival in 1973, where there was a rush to the exits by viewers unprepared for its ebullient psycho-sexual imagery, and who, evidently expecting something more in the Disney line, had brought their children.

The days when something like this might be seen as a viable commercial exercise for an animation studio seem as distant as the pre-rational world it depicts, and Belladonna still packs quite a punch, even for a work from a country whose animation is often celebrated for its lack of restraint.

Belladonna of Sadness is released on UK Blu-ray by Anime Limited.

Leave a Reply