To Sleep So As to Dream

May 17, 2022 · 0 comments

By Tom Wilmot.

After her daughter, Bellflower (Moe Kamura), is kidnapped by the shady M. Pathé company, Madame Cherryblossom (Fujiko Fukamizu) reaches out to private investigator Uotsuka (Shiro Sano) for help. Along with his assistant Kobayashi (Koji Otake), and a whole load of boiled eggs, Uotsuka embarks on a seemingly endless hunt for the missing woman. However, as the mystery unravels, past and present, along with fiction and reality, all converge to reveal the truth.

To produce what is essentially a silent film, intertitles and all, in the 1980s is daring enough, but to make such a project your debut feature is a tremendous undertaking. Yet this is precisely what the 27-year-old Kaizo Hayashi did with To Sleep So As To Dream. Perhaps most remarkable of all is that the film turned out to be nothing short of a masterpiece. It’s difficult to overstate just how technically impressive Hayashi’s feature is on every level. For a start, the sound design is magnificent, with the director only using sounds that he deemed to be “essential” for the narrative. Telephones ring, but no voices answer, as Hayashi relies on action over words to tell his tale. The silent elements of the film evoke the essence of pure cinema, while the selective inclusion of diegetic and non-diegetic sounds and music makes for a unique and unorthodox picture.

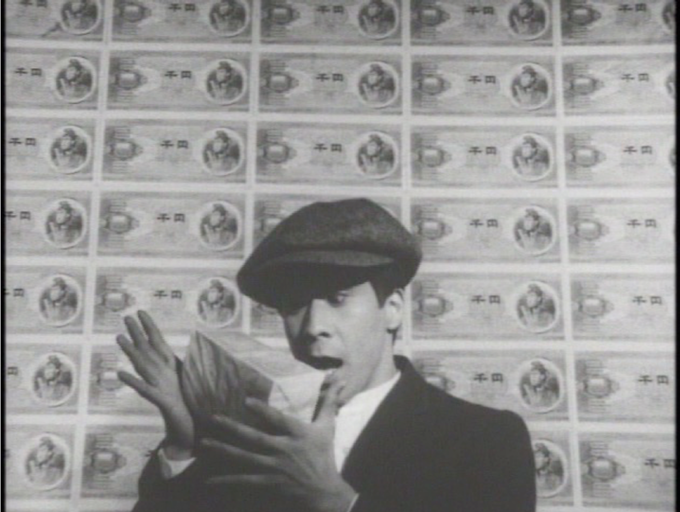

Shot on 16mm monochrome film, Hayashi’s feature is as staggeringly beautiful as it is technically sound. The high contrast between blacks and whites and the carefully considered use of shadow and light results in a stunning period piece that is noir-like in its visuals. Hayashi’s general love for silent cinema is prevalent, as the film features flashes of German Expressionism and shot composition typical of Japanese productions from the late 1920s. There’s also the incorporation of sets designed by frequent Seijun Suzuki collaborator Takeo Kimura, which add to the film’s otherworldly nature. As well as the contemporary visuals, the fictional film within the film, ‘The Eternal Mystery’, is such a faithful recreation of early, silent swordplay features that it’s hard to believe you’re not watching archival footage.

The film is a love letter to silent cinema in almost every aspect, including its dreamlike narrative. What starts out as a hard-boiled detective story evolves into a surreal journey through cinematic history that blurs the line between past and present. Shiro Sano has a face made for the big screen, as he, along with much of the supporting cast, have a gripping screen presence that is perfect for a silent film. Akira Oizumi’s reappearing magician is a particular stand-out, coming across as a pantomime villain with devilish looks. There’s also the heartfelt presence of Fujiko Fukamizu, a prominent actor who had last graced the screen in 1941. Both in front of and behind the camera, a massive amount of talent has gone into this timeless project, with every achievement made all the more impressive when considering the film’s microbudget.

Of all the key areas of Japanese cinema history touched upon in To Sleep So As To Dream, that which concerns the benshi is the most interesting. Benshi were performers who would accompany showings of silent films and provide a dramatized narration for audiences. Usually joined by live musicians, benshi would perform the voices for each character and put on a show for cinema-goers. Benshi were immensely popular in the heyday of Japanese silent cinema, with certain performers being a bigger draw for audiences than the films themselves. Inevitably, the development of ‘talkies’ meant that the benshi disappeared into obscurity. However, it’s worth noting that the somewhat tardy popularity of sound films in Japan was partly down to the benshi’s influence and enduring popularity.

The continued presence of benshi, albeit minimal, in the world of Japanese cinema has persisted in part thanks to Shunsui Matsuda. A former benshi himself, Matsuda features in To Sleep So As To Dream in a sequence where he narrates over ‘The Eternal Mystery’. Matsuda was a significant figure in the post-war era, as he took it upon himself to save a number of silent film prints from destruction. His benshi performance in Hayashi’s film gives us a taste of a lost cinema-going experience that was part of a significant period in the early years of Japanese cinema.

Giving us the lowdown on the history of the benshi is none other than Matsuda’s apprentice and Japan’s most popular practising benshi, Midori Sawato. Also featured in Hayashi’s film as a knife-throwing performer, Sawato trained under Matsuda and now works as the few active benshi. The animated and passionate performer discusses everything from a fateful viewing of Kenji Mizoguchi’s The Water Magician (1933) that drove her to become a benshi to what became of popular benshi when their art was no longer deemed necessary. Sawato also performs a new benshi reading for ‘The Eternal Mystery’. To make such a unique performance so widely available is something to be commended, as it breathes life into an artistic practice that remains an essential part of Japanese cinema history.

Lending their voices once more to an Arrow Video audio commentary are the dynamic duo of Jasper Sharp and Tom Mes. The former Midnight Eye authors delve into the careers of the lesser-known contributors to Hayashi’s film, including the aforementioned Takeo Kimura and cinematographer Yuichi Nagata. The two also discuss the lack of scholarly attention that has been paid to Japan’s cinema of the 1980s, although this is something that has been rectified in times of late. You’ll come out of this particular commentary track sufficiently clued up on the historical context surrounding this film and Hayashi’s subsequent works.

Also available in this release is an archival audio commentary featuring the director Kaizo Hayashi and the film’s star, Shiro Sano. Speaking in 2000, the pair look back fondly on the production, scoffing at their lack of filmmaking experience, with Hayashi sharing several charming anecdotes. In a newly recorded interview, Sano discusses his philosophical views on acting and how he learned from his peers while making his first feature film. A prolific actor in both film and television, Sano says he still carries the character of Uotsuka into every role.

Accompanying the first-pressing of this Blu-ray set is a booklet containing a heartfelt director’s statement from Hayashi and an original essay by Aaron Gerow. The film scholar delves into the timeline errors present in Hayashi’s film but, rather than criticising them, discusses how these intentional inaccuracies play into the film’s feeling of “temporality”. Gerow assesses the reccurring narrative themes of Hayashi’s filmography and convincingly argues the significance of a debut feature melding past and present. The cherry on top of this superb package is a couple of clips from rare silent films from the Kyoto Toy Museum archive.

To Sleep So As To Dream is essential viewing for lovers of film history and East Asian cinema. The film is a heartfelt and technically stunning ode to an oft-overlooked era of Japanese cinema. Not only is the picture brilliant in its own right, it also benefits from the years of cinematic history that it celebrates. Arrow Video’s set is a must-have release, not just for Hayashi’s tranquil film but for the attention that has been paid to vital aspects of Japan’s film history.

To Sleep So As To Dream is released in the UK by Arrow Films.

Leave a Reply