Toshiaki Toyoda

January 24, 2022 · 0 comments

By Tom Wilmot.

When people think of the new masters of Japanese cinema, the same roster of names continues to crop up. Hirokazu Koreeda, Kiyoshi Kurosawa, and Takashi Miike, among others, tend to be the usual suspects as far as international acclaim goes. However, there is another director whose consistently introspective, vibrant, and brutal work has flown almost entirely under the radar, and that is Toshiaki Toyoda.

The director has faced uphill battles for most of his career, in part because of two very public arrests, first in 2005 and again in 2019. However, being shunned by the Japanese film industry hasn’t soured Toyoda’s appetite for filmmaking, nor has it dampened his raw talent. Following up on their 2016 boxset exploring the director’s electrifying early works, Third Window Films return with another release celebrating the films of Japan’s neglected cult filmmaker.

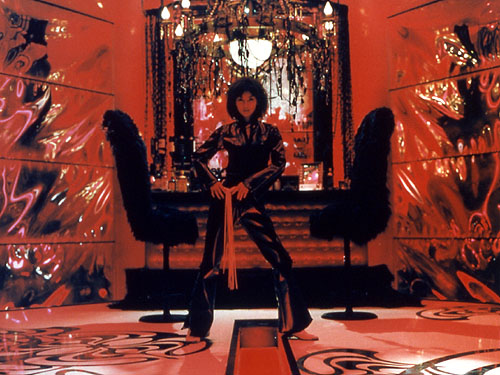

Following the critical success of 9 Souls (2003), Toyoda moved forward with his next project, 2005’s Hanging Garden. The film is a stylistic drama that critiques modern Japanese family life, much like Takashi Miike’s Visitor Q (2001) and Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s Tokyo Sonata (2008). Eriko Kyobashi (Kyoko Koizumi) is a housewife who is determined to maintain the illusion of happiness despite the clear issues under her roof, as a means of moving away from her troubled childhood.

Those familiar with Toyoda’s earlier films will no doubt notice Hanging Garden’s differences in everything from tone to pacing. Gone are the aggressive undertones in both the soundtrack and dialogue, as the director instead makes way for touching monologues and a softer score. There’s also the repetitive lull of a swaying camera that is a move away from the kinetic visuals of his first few films. It’s a testament to Toyoda’s versatility as a filmmaker that all these stylistic changes are executed faultlessly.

Perhaps the biggest departure Hanging Garden makes from Toyoda’s prior films is the clear focus on female characters. The narrative primarily follows three generations of women in the Kyobashi household, with all of them searching for meaningful connections through one another. The delicacy with which the family ties are presented is reasonably grounded and wholly sincere. This focus is made all the better by some wonderful performances, with Michiyo Ohkusu stealing the show as the sassy grandmother, Satoko. A masterful one-take sequence between her and Koizumi is a stand-out.

The excitement surrounding what was to be Toyoda’s most high-profile film to date was cut short when he was arrested in 2005, mere weeks before the release. The director was charged with drugs possession and handed a suspended sentence that effectively banned him from filmmaking for four years. Hanging Garden still made its way to Japanese theatres later that year, but the director’s reputation was irreversibly tainted.

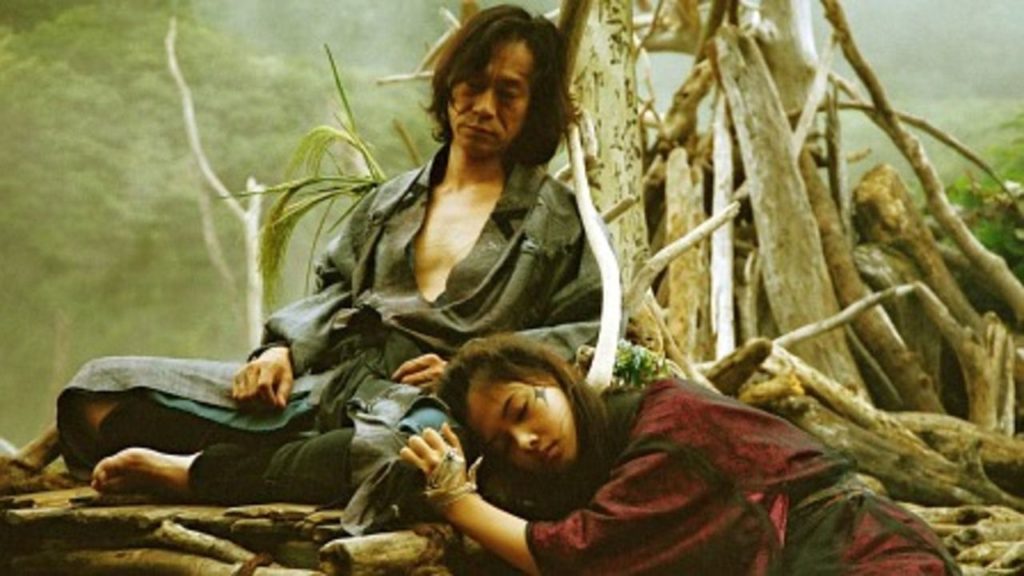

It wasn’t until 2009 that Toyoda returned to directing with the aptly titled The Blood of Rebirth, which he then followed up with the 2011 film Monsters Club. The latter is about as close to a direct horror film as Toyoda has made, with the plot taking place in an isolated cabin in the snowy mountains. Ryoichi (Eita Nagayama) is a disillusioned soul who has rejected modern society to live alone in the forest. In his spare time, he sends homemade bombs to advertising companies and marketing CEOs in a solo attempt to bring about some sort of societal change.

The film marks another distinct change in pace from Toyoda, with the raw energy of his earlier works making way for a more methodical visual and narrative approach. This film is one of the director’s most depressing, as, through Ryoichi, he takes us on a solitary journey of evaluating purpose and self-worth. Ryoichi’s disillusionment with modern society is entirely nihilistic, and the opening portion of the film is dominated by his internal monologues that liken working life to modern slavery and draw attention to some sobering statistics concerning suicide.

As if an existential crisis of extreme proportions wasn’t terrifying enough, the film also has some of the most disturbing imagery of any Toyoda project. While the director’s over-the-top violence does rear its head in moments, it’s more the atmospheric horror and unsettling images that conjure up the most discomfort. The apparitions of Ryoichi’s dead family members are disturbing in their own right, which is then made tenfold when they appear covered in what is revealed to be coloured shaving cream. The premise of being stalked in the frozen mountains is terrifying enough, let alone when the stalkers are ghostly figures encouraging suicide.

Despite the doom and gloom, Monsters Club proves to be one of Toyoda’s more optimistic films come the finale. There’s a beauty and contemplativeness in the ambiguity of the narrative, as it’s unclear whether Ryoichi has re-evaluated his place in the world or succumbed to his nihilistic beliefs. I choose to believe the former, but the door is wide open for interpretation. Despite being one of Toyoda’s most minimalistic films, it’s easily one of his most gripping and potentially the strongest feature in this set.

The final feature film in Third Window Films’ release is Toyoda’s 2012 effort, I’m Flash. The film follows religious leader Rui, played here by Battle Royale (2000) star Tatsuya Fujiwara. After a devastating car accident, Rui questions his place in the world and seeks to escape his cult-like organisation. Followed by indifferent bodyguards whose only concern is money, Rui recalls the night leading up to the car crash as he looks for a way out.

I’m Flash could have been a yakuza-esque flick along the lines of Toyoda’s 1998 film Pornostar, but it instead exercises restraint to be one of the director’s more pensive projects. Toyoda uses the backdrop of the religious cult to, once again, look for deeper meaning in the individual. Like Monsters Club, the film is filled with extended internal monologues consisting of lofty dialogue that explores the very nature of existence. Far from being pretentious, though, I’m Flash presents its ideas in an accessible manner that is genuinely thought-provoking.

Set on the tropical island of Okinawa, the film has its fair share of sun and blood-soaked imagery. One location, in particular, is littered with skulls, candles, and all the other hallmarks of typical cult horror. We also see the return of Toyoda’s tendency for stylised violence, with a surprise shootout marking one of the film’s few explosive sequences. There’s also something to be said about how the cult is presented as a yakuza organisation of sorts, with bribery and murder being overseen by its chilling matriarch, played wonderfully by a returning Michiyo Ohkusu.

I’m Flash further tracks the stylistic change in Toyoda’s filmmaking. The loud and abrasive approach of his early work is in complete contrast with the brooding and evenly paced nature of the films in this set. If anything, these features prove that you cannot place Toyoda in a box, as, despite some reoccurring visual cues and narrative themes, his movies are wildly varied in execution.

Toyoda’s stagnated return to the film industry was dealt another blow when in April 2019 he was, once again, publicly arrested, this time for firearms possession. However, he was soon released after the weapon in question was found to be no more than an antique World War II pistol. Fortunately, this setback didn’t deter the filmmaker from moving forward with his next project, a trio of short films that would become the so-called “Resurrection Trilogy”.

The first in the series is the 16-minute-long Wolf’s Calling (2019), which Toyoda made as a direct response to his recent arrest. The dialogue-free film is a tense affair and is based on the director’s experience of being arrested. We open with a young woman finding an antique handgun in her home, which leads directly into an extended scene in which several samurai gather at the Mt Resurrection Wolf shrine, a location that features prominently in all three short films. There’s little to garner in terms of meaning from Wolf’s Calling, but the film does showcase Toyoda’s ability to craft an intimidating and suspenseful atmosphere through pure filmmaking alone.

Next up in the trio of shorts is the 2020 film, The Day of Destruction, which at 57-minutes, is nearly feature-length. This short is the most narratively driven of the trilogy, although it too remains ambiguous in terms of meaning. As with many of Toyoda’s films, multiple interpretations can be taken from the project, although this is definitely one of his more experimental stories. The connecting location of the Mt Resurrection Wolf shrine features heavily in the film as we dance between monster-induced epidemic and demon possession subplots.

The final entry in the trilogy is the 2021 short Go Seppuku Yourselves, a 26-minute jidaigeki centred around the ritual suicide of a samurai accused of spreading poison throughout a town. It’s hard not to make a connection between COVID-19 and the epidemics featured in both The Day of Destruction and Go Seppuku Yourselves, particularly given when the shorts were produced. However, rather than illness being the focus, the director uses the film to spout damnation towards the powers that be through the samurai in question, who’s played by Toyoda regular Yosuke Kubozuka.

Supplementing the films are a couple of interviews with Toyoda in which he talks about the trials he’s faced throughout his turbulent career. It’s particularly interesting to hear the director go in-depth on the motivations behind his short films, with The Day of Destruction primarily being made to spite the Tokyo Olympics, which he was vehemently against. It’s remarkable just how understanding Toyoda is of his film industry shunning and sad to think of how much grander his career could have been if he was granted more opportunities. However, considering the micro-budgets he’s had to work with, we should be grateful for some of the brilliant films he has been able to produce.

Along with his interviews, Toyoda also provides audio commentary for Hanging Garden, in which he discusses the production behind the film. The director, who’s re-watching the film for the first time in some 17 years, touches on the execution of the more challenging sequences and notes some instances of magnificent improvisation on the part of the cast. Providing commentaries for Monsters Club and I’m Flash are the usual suspects of Jasper Sharp and Tom Mes, respectively. The pair have a history of covering Toyoda’s early works on the website Midnight Eye, and both demonstrate their extensive knowledge of the director with fact-filled audio tracks.

As this new release from Third Window Films proves, Toshiaki Toyoda’s breadth of filmmaking talent seemingly knows no bounds. The cinematic style and overall nature of his projects have evolved so that he’s built up a diverse and provocative body of work throughout his twenty-year plus career. Toyoda’s examination and critique of everything from traditional institutions to one’s self-worth make his films extremely engaging. Pair this rich thematic approach with a distinct visual style, and you have all the makings of an auteur whose voice is a valuable one in the current landscape of Japanese cinema.

Toshiaki Toyoda 2005-2021 is released in the UK by Third Window.

Leave a Reply