When the Wind Blows

January 21, 2018 · 0 comments

By Andrew Osmond.

“They say it’s the correct thing to wear white. People in Hiroshima with patterned clothes got burned where the patterns was and not so much on the white bits. Even the buttons showed up.”

“They say it’s the correct thing to wear white. People in Hiroshima with patterned clothes got burned where the patterns was and not so much on the white bits. Even the buttons showed up.”

“Yes, but they were Japanese.”

In the late 1980s, two unusual animated films were released aimed at adults; both had images of nuclear apocalypse, and both had Japanese or Japanese-American directors. One was Katsuhiro Otomo’s Akira. The other was When the Wind Blows, a British animation, directed by Jimmy Murakami.

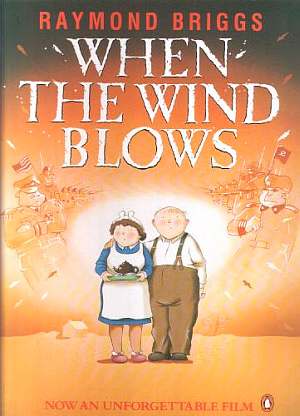

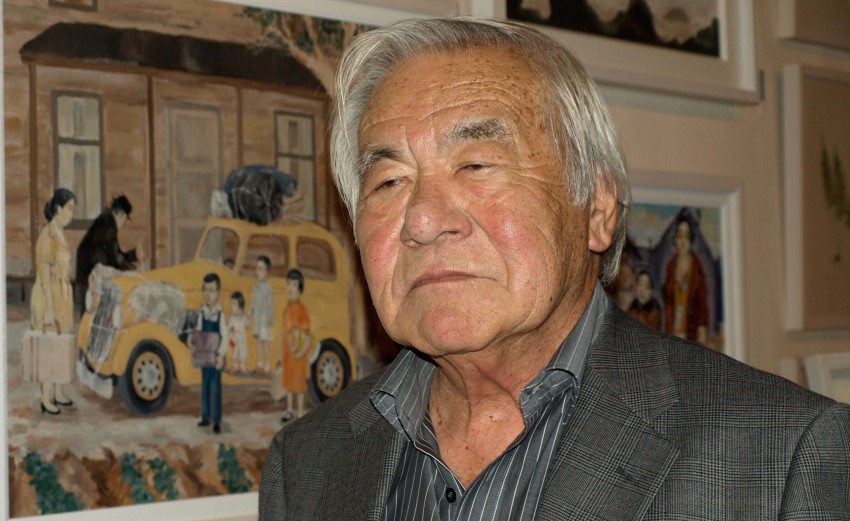

When the Wind Blows is being released in a new home edition by the British Film Institute, containing the film on both Blu-ray and DVD. But what’s especially significant about this edition are its new insights into the director. The extras include a second, live-action film, a 72-minute documentary called Jimmy Murakami: Non-Alien. Made four years before Murakami died in 2014, it focuses on his traumatic childhood experiences of war – not in Japan, but in America. For Murakami was one of thousands of Japanese illegally imprisoned in American concentration camps after Pearl Harbor. The documentary shows him still trying to come to terms with that fact.

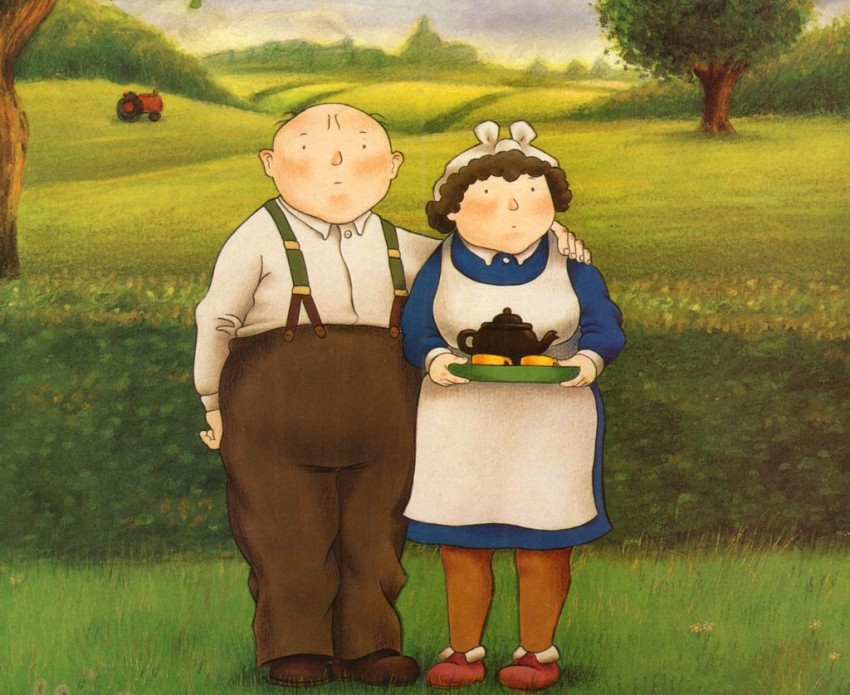

Taking When the Wind Blows first, it’s a satirical drama about a retired English couple, Jim and Hilda Bloggs, who live in a remote cottage on the South Downs in Sussex. The film is full of loving domestic details, cooking and eating especially, even as it shows what happens to Jim and Hilda in the apocalypse. Russia hits Britain with a nuclear strike, but the couple continues to trust in Britain – its authorities, its politicians, its stiff upper lip – even though their surroundings are a black wasteland and everyone else is dead. Of course it’s an anti-war film, and a depiction of the nuclear nightmare. It’s also an attack on British attitudes, British narratives, British complacency as insane as nuclear war itself.

The story wasn’t created by Murakami, but by the British artist Raymond Briggs, who’s best known as the creator of the picture book The Snowman (1978), the basis of the cartoon of that name. Apart from When the Wind Blows, Briggs’ other books include Father Christmas (which turns Santa into a grumbling curmudgeon), Fungus the Bogeyman and The Bear. The books are acerbic, downbeat (remember the end of The Snowman) and subversive. Fungus the Bogeyman has existential angst, questioning why he spends his life scaring humans. Another Briggs book, Gentleman Jim, depicts a childlike toilet attendant whose antics bring authorities crashing onto him, far sillier than Jim himself. He’s theoretically the “same” character as the Jim in When the Wind Blows.

The story wasn’t created by Murakami, but by the British artist Raymond Briggs, who’s best known as the creator of the picture book The Snowman (1978), the basis of the cartoon of that name. Apart from When the Wind Blows, Briggs’ other books include Father Christmas (which turns Santa into a grumbling curmudgeon), Fungus the Bogeyman and The Bear. The books are acerbic, downbeat (remember the end of The Snowman) and subversive. Fungus the Bogeyman has existential angst, questioning why he spends his life scaring humans. Another Briggs book, Gentleman Jim, depicts a childlike toilet attendant whose antics bring authorities crashing onto him, far sillier than Jim himself. He’s theoretically the “same” character as the Jim in When the Wind Blows.

The new edition of the film doesn’t really discuss the artistic meeting between Briggs’ and Murakami’s sensibilities. However, it does offer vivid portraits of both creators. Briggs appears in a 25-minute “making-of” film, “The Wind and the Bomb” and in a 14-minute interview from 2005. Briggs is still with us today, but doesn’t make any more recent contribution to this edition; quite possibly he’s said all he wants to about a 36-year-old book. He presents himself as a dour depressive, though on screen he’s courteous, gentlemanly and good-humoured – that was also my experience when I did a phone interview with Briggs in the 1990s.

For Briggs, the starting point was seeing a 1980s Panorama documentary about the prospect of a nuclear attack (it seems to be this one here, narrated by a young Jeremy Paxman). Briggs read the official government leaflets about how to survive, and found them “ready-made comic material”. His next inspiration was his own late parents. Briggs describes the Jim and Hilda characters as a “fairly typical English working class couple, not as stupid as many people have made out, I think they’re perfectly sensible… simple, but not stupid by any means. These people were meant to be based on my parents, and they were of that generation… They were fairly simple, uneducated people.” Briggs’ parents also were the inspiration for his later Ethel & Ernest, recently adapted into an animated film.

In the making-of, Murakami also discusses Jim and Hilda, and his comment is especially notable. “(They) are sort of nostalgic, they’re not stupid people. The only thing they can remember is the Second World War and what they’ve gone through during the Blitz in London, that’s what they remember. They think that all wars are similar.”

Murakami’s own background was extremely different. As the Non Alien documentary explains, he was just seven when he and his family, living in America, were interned in a prison camp at Tule Lake, a dry lake in North California near the Oregon border. The reason was the Pearl Harbor attack, and the reactions of people such as Congressman John Rankin, who told the House of Representatives: “I’m for catching every Japanese in America, Alaska and Hawaii now and putting them in concentration camps… Damn them! Let’s get rid of them now!” (No prizes for guessing which contemporary politician isn’t convinced that the internment violated American values.)

Jimmy and his mother were American-born and American citizens. Jimmy’s father wasn’t; he was still a Japanese citizen, which put him in a bind when he was presented with a notorious loyalty test. It asked if he would serve in the US armed forces, and forswear any allegiance to Japan’s Emperor. If Jimmy’s father answered yes, he would lose the only citizenship he had. He answered no, and he and his family were detained indefinitely at Tule lake, together with 18,000 others, guarded by tanks and armed soldiers. The situation is depicted through Murakami’s own paintings, simply animated. While there don’t seem to be any anime about this time, Giovanni’s Island depicts a comparable based-on-fact situation, where Japanese islanders have their home occupied by Russia and children suffer in a Soviet prison camp.

Jimmy and his mother were American-born and American citizens. Jimmy’s father wasn’t; he was still a Japanese citizen, which put him in a bind when he was presented with a notorious loyalty test. It asked if he would serve in the US armed forces, and forswear any allegiance to Japan’s Emperor. If Jimmy’s father answered yes, he would lose the only citizenship he had. He answered no, and he and his family were detained indefinitely at Tule lake, together with 18,000 others, guarded by tanks and armed soldiers. The situation is depicted through Murakami’s own paintings, simply animated. While there don’t seem to be any anime about this time, Giovanni’s Island depicts a comparable based-on-fact situation, where Japanese islanders have their home occupied by Russia and children suffer in a Soviet prison camp.

“Even a car thief knows how long he’s going to be in jail,” Murakami notes in the documentary. The category “non alien” was invented to avoid referring to people like him as American citizens, who were being denied the rights of American citizens. The internment order came not from John Rankin but from President Roosevelt himself. In When the Wind Blows, Jim and Hilda remember Roosevelt as a “nice chap”, alongside Churchill and Stalin. Jimmy’s family was imprisoned for four years; his older sister Sumiko succumbed to leukaemia during that time. When they were released, the family was given passes for a train to Los Angeles, with three suitcases and the box of Sumiko’s ashes.

Highly moving, the No Alien film shows a Murakami not given to tears or emotional displays, as he explains what internment did to him. He cites the 9/11 hijackers – “They have only one belief in one thing. We were trained to be that way here (at Tule Lake), to be a Japanese soldier dying for their country… I was only 8, 9, 10 years old… If Japan had invaded America, I would have strapped a bomb to my body and committed suicide for Japan. This was something that was embedded in me. This is the thing that’s happening all over the world now.”

After internment, Murakami struggled to find an identity. A “mean bastard” who ran with gangs as a schoolboy, he found a better calling when he received a scholarship to the Chouinard Art Institute, precursor to CalArts. With a fine arts education, he developed a career in animation, making several acclaimed short films (some extracts are shown in No Alien.) But he was still unsettled, never at peace. “I was really scared of not being accepted in life, I felt I was put in the gutter and that was where I was going to stay.” That lasted till he found a home thousands of miles away – in Ireland, where he would live for the last four decades of his life. Much of No Alien centres round a “pilgrimage” Murakami made to California in his seventies, travelling with other former internees back to the site of his childhood prison.

Murakami’s extensive career goes beyond animation. In the wake of the original Star Wars, for instance, Murakami directed the live-action Battle Beyond the Stars, reworking Seven Samurai with spaceships; it had models and effects by a promising youngster called James Cameron. Later, he was supervising director on the animated Snowman, but admitted it wasn’t to his taste. In contrast, When the Wind Blows was “the kind of film I wanted to make.” On a commentary track, Joe Fordham, who worked as first assistant editor, describes Murakami as “very robust”, tough but even-tempered; he’d invite people to punch him in the stomach, cite Kurosawa films (unsurprisingly, given his CV) and give animators one-to-one guidance. I interviewed Murakami about his career twice, here, and here.

Murakami’s extensive career goes beyond animation. In the wake of the original Star Wars, for instance, Murakami directed the live-action Battle Beyond the Stars, reworking Seven Samurai with spaceships; it had models and effects by a promising youngster called James Cameron. Later, he was supervising director on the animated Snowman, but admitted it wasn’t to his taste. In contrast, When the Wind Blows was “the kind of film I wanted to make.” On a commentary track, Joe Fordham, who worked as first assistant editor, describes Murakami as “very robust”, tough but even-tempered; he’d invite people to punch him in the stomach, cite Kurosawa films (unsurprisingly, given his CV) and give animators one-to-one guidance. I interviewed Murakami about his career twice, here, and here.

An obvious question this new release raises, given it packages No Alien together with When the Wind Blows, is whether the films are complements in some thematic way. Wind Blows mocks the nostalgic British narrative of World War II, the “good war”. While this mockery is present in Briggs’ comic, the film accentuates it further still. In the most on-the-nose moment, before the bomb falls, Jim and Hilda share wartime memories: “the shelters, the blackout, cups of tea, old Churchill on the wireless…” The animation gives way to archive images of all these things, in a split-screen monochrome montage set to an off-key “Rock-a-bye baby.”

It’s a lampoon of nostalgia as a lie for children and childlike people. That seems telling, given that this is a film whose director was imprisoned by his country because of patriotic narratives, and who wanted to be a suicide bomber by the age of eight.

For all Briggs’ and Murakami’s claims to the contrary, Jim and Hilda do seem ludicrously childish and stupid in the film. The later scenes have horror and pathos, with heart-breaking voice performances by John Mills and Peggy Ashcroft, yet the film is smug in a way that separates it from other nuclear nightmare films of the 1980s, like The Day After and Threads. As critic Kim Newman says in his book Millennium Movies, When the Wind Blows “is unusual in assuming its audience knows more about nuclear war than its characters.” Rather than demonise the other side – which the film suggests isn’t Russia but rather anyone stupid enough to believe in nuclear deterrence – When the Wind Blows infantalises them as sheeple, not empowered enough to have a view worth debating.

Yet the film fascinates, not least as an adult, provocative, technically innovative cartoon that’s a feat of mixed media. Nearly all the action takes place in the Bloggs’ house, which Murakami wanted to look convincingly three-dimensional, with flexible camera angles. CG wasn’t an option (the film came out in the year of Pixar’s lamp experiment Luxo Jr). Instead, Murakami used a phenomenally hard hybrid technique to place Jim and Hilda, traditionally animated characters, into a physical miniature model. It would take too long to explain here, but there’s an excellent summary in a booklet included with the new edition, in an essay by Clare Kitson. Of course you can see the joins on screen between the real and drawn elements, but that’s part of the charm, like the classical stop-motion of the first King Kong.

Some of my own favourite moments in the film are bodges or “mistakes”; for example, an early, feathery patch of flower-and-fairy animation by Snowman director Dianne Jackson, imagining Hilda’s soppy-erotic daydreams. Briggs and Murakami disliked it, but it’s a lovely grace note. Then there are the images in the film’s final moments. They involve spud sacks, and are quite terrifying. They were meant to be animated “properly” but a schedule crisis meant the production had to use photos and cross-dissolves instead. The result’s unique: a mix of haunting surrealism, tender absurdity and utter sadness to have viewers in tears.

Was it the creators’ last word on the wind and the bomb? Maybe it was for Briggs, but until he died, Murakami was developing an animated film script, provisionally as a Japan-Ireland co-production, called The Girl in the Green Kimono. He described it as a love story/drama, set in Hiroshima both before and after the Bomb. Perhaps it would have had points of contact with Sunao Katabuchi’s In This Corner of the World. But surely it would have had personal resonances for Murakami, as an account of the sufferings of war, but also of living beyond it.

Andrew Osmond is the author of 100 Animated Feature Films.

Leave a Reply