Yokai Monsters

February 18, 2022 · 0 comments

By Tom Wilmot.

Yokai have been a point of fascination for film fans for many years. The word Yokai in very general terms means “strange thing”, and is used to label creatures that have, according to folklorists, been around for hundreds if not thousands of years. These bizarre creatures have popped up in video games, manga, anime and, of course, films. Yokai are a special part of Japanese culture as their very existence provides a window into the past, albeit a murky one.

The pre-20th century popularity of yokai in novels and kabuki theatre meant that they were destined to be a constant presence in Japanese cinema. While yokai have featured prominently in everything from silent samurai movies to J-horror, one of the largest gatherings of cinematic yokai can be found in Daiei studio’s Yokai Monsters trilogy, which is the latest franchise from the defunct studio to get the Arrow Video treatment.

Screenwriter Tetsuro Yoshida, who also wrote all three Daimajin films, is the creative voice behind every entry. Incidentally, Kimiyoshi Yasuda, who directed the trilogy opener, 100 Monsters (1968), also helmed 1966’s Daimajin, so perhaps it’s no surprise that this first entry follows a similar story. A corrupt group of officials oppress a group of lowly villagers and disregard their beliefs, only for a group of morally ambiguous yokai to appear in the final act and save the day. It’s a fun if predictable plot that has sprinkles of mischief dotted throughout before the grand, special effects-heavy finale. One earlier sequence of note, however, is a fantastic partially-animated scene in which one yokai becomes part of a wall and dances for an understandably dumbstruck adult.

It’s with Yoshiyuki Kuroda’s Spook Warfare (1968) that stuff gets really funky. In the opening fifteen minutes, we’re introduced to an ancient Babylonian monster of the vampiric persuasion that takes control of an unsuspecting Japanese lord. Unlike 100 Monsters, the second film is far more yokai-centric, with a goofy-looking band coming together to fight an all-out war against the Babylonian terror. Spook Warfare is easily the most entertaining entry in the trilogy, and, while being shamelessly camp, it’s also the creepiest. This is in no small part down to Sei Ikeno’s eerie and foreboding score, which is layered over atmospheric shots of misty forests. Of course, all tension goes out the window when a man in a kappa costume starts splashing about in a pond with his head on fire, but these tonal shifts are what make the film such great fun.

The wackiness of Spook Warfare and its disinterest in the human characters means that the final film in the trilogy, Along with Ghosts (1969), is something of a disappointment. The yokai presence in the narrative is entirely incidental, with their appearance feeling shoe-horned in for the sake of the title. However, when viewed as a swordplay film, Along with Ghosts is arguably most compelling of the three. The noble ronin Hyakasuro (Kojiro Hongo) rescuing the young Miyo (Masami Burukido) and shielding her from evil pursuers brings a Lone Wolf & Cub type element to the narrative, with co-director Kuroda actually going on to direct the sixth entry in that particular series. While entertaining as a samurai flick, the film barely has any claim to being a yokai movie, other than the title. The yokai that do feature are crusty, ghost-like figures who are mostly bathed in shadow.

The trilogy brings to mind Shintoho’s earlier attempt to put several yokai on the silver screen with Goro Kadono’s 1957 film Ghost Stories of Wanderer at Honjo. That film featured many of the monsters seen in the Yokai Monsters series, notably the faceless nopperabo and the loveable umbrella-like kasa-bake. The biggest difference with Daiei’s films just over a decade later is the eye-popping colours and glorious special effects. While not all of the SFX work on the series has aged entirely well, there’s still an awful lot to admire about the ambition. The long, winding neck of the rokurokubi as well as dancing flames and ghostly apparitions are all presented expertly given the budget behind each film. It’s also refreshing to go back and watch a tokusatsu movie that isn’t of a Godzilla or Daimajin sized scale, as the smaller, cheaper effects are devilish in their creativity.

One of the best parts of the series is how each film integrates and plays with actual yokai lore. In 100 Monsters, the hyaku-monogatari (one-hundred stories) is a crucial part of the plot and acts as a clever framing device for the appearance of the Yokai through spooky vignettes. Each film also ends with a depiction of the hyakkiyagyo, which translates as “night procession of one hundred oni”. These sequences are ghostly in their execution and, at least in the case of Spook Warfare, oddly touching. Fans of the Studio Ghibli classic Pom Poko (1994) will recall a similar hyakkiyagyo sequence in which a group of pesky tanuki put on a marvellous display in the hope of scaring off invaders.

Some thirty years after Daiei declared bankruptcy, prolific filmmaker Takashi Miike revitalised yokai cinema with his 2005 film, The Great Yokai War. The film, which is also included in this set, is a reimagining of Spook Warfare, with the plot following the young Tadashi (Ryunosuke Kamiki), who finds himself at the centre of a yokai conflict that could mean the end for humanity. Unfortunately, Tadashi’s character arc and Kamiki’s performance are the most compelling parts of an overly long affair. He and the yokai face off against the evil Lord Kato (Etsushi Toyokawa) and his band of robot-yokai minions, but there’s little to grasp onto in what is primarily an adventure film aimed at children – aside from the odd injection of violence.

The refined costume designs are much grittier than those of the Daiei trilogy, with many of the yokai looking more realistic than ever. Yet, the goofiness of the 1960s efforts is still there, providing the film with a welcome playfulness. Despite this, it must be said that what was cutting edge in 2005 in terms of SFX now looks extremely tacky, which is a shame as there is a lot of ugly CGI on display. As odd as it might seem, the 1960s trilogy has actually aged better visually than Miike’s effort, with even the crudest of practical effects being far less jarring than robots that look like they’ve been ripped straight from a PS2 cutscene. While it has its merits, Miike’s film more so highlights the technical achievements of its predecessors.

Lending his voice to the audio commentary for The Great Yokai War is Japanese cinema expert Tom Mes. The author, who has written two books on Miike, is the definitive source of information on the acclaimed director and offers up another fact-filled audio commentary that’s less concerned with the film’s content than its surrounding context. One interesting observation Mes makes is that The Great Yokai War shares some of the hallmarks of Studio Ghibli’s films, notably that the countryside setting is used as a gateway to traditional Japan. Mes also touches on the fact that the project marked a turning point of sorts in Miike’s career, with the filmmaker moving away from low-budget, quick turnaround projects in favour of larger-scale studio work. Alongside Mes’ commentary, there’s a wealth of archival behind the scenes footage packed into this release, as well as four short films.

In terms of new bonus material, Arrow has put together the 40-minute documentary, Hiding in Plain Sight: A Brief History of Yokai. This extended featurette is overloaded with information about Japan’s famous native monsters, which is enthusiastically delivered by Kim Newman, Zack Davisson and several other authors of film and yokai-related material. This documentary is essentially a Yokai 101 for the uninitiated, so watching it before the films will give you a clearer idea of the history and folklore behind the mythical creatures on display. A tidbit of note for anime fans is that Davisson credits the immense popularity of Demon Slayer: Kimetsu no Yaiba with bringing back the latest wave of interest in yokai.

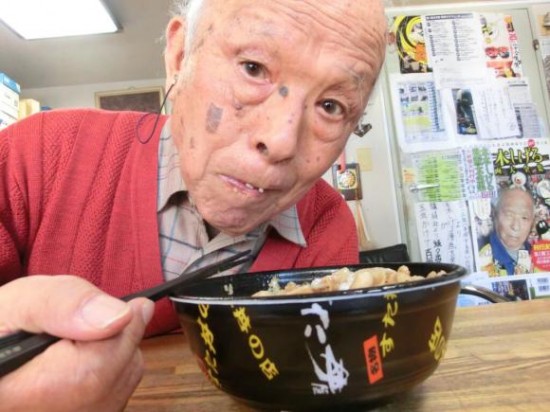

One vital figure in the history of Yokai pop culture is the late, great manga author Shigeru Mizuki. His seismic impact is covered in both Hiding in Plain Sight and a revised article written by Jolyon Yates. The author’s immensely popular works helped keep yokai in the public consciousness in post-war Japan and contributed to the so-called “Yokai boom” of the 1960s. It’s wholly fitting and a tad melancholic that Mizuki, who passed away in 2015, has a cameo appearance as the Great Yokai Lord in Miike’s 2005 film. Arrow’s comprehensive booklet also has essays from Stuart Galbraith IV, who delves into the history and development of yokai cinema, and Rafael Coronelli, who takes us on a Yokai sightseeing tour of sorts, at least as far as Daiei’s trilogy is concerned.

Yokai, as they have done throughout history, continue to proliferate, evolve, and seep their way into popular culture. The Yokai Monsters trilogy is only one example of how these mystifying creatures have found their way to the big screen. There’s something undeniably wonderous about how Daiei and Miike’s films have contributed to the development of a mythology that is woven into the fabric of Japanese culture. Arrow Video’s set is clearly a labour of love, with everything from the excellent presentation of the films to the beautifully illustrated packaging paying homage to this weird and wonderful world.

The Yokai Monsters box set is released by Arrow Video.

Leave a Reply