Anime Studies: Ten Books To Own

December 13, 2015 · 2 comments

By Andrew Osmond.

So you love Japanese animation, and want to make yourself an expert. Of course you use Google and Wikipedia to broaden your knowledge, but web sources are reliably unreliable, especially when discussing a medium rather older than the internet. Sometimes there’s no alternative to hitting the books.

So you love Japanese animation, and want to make yourself an expert. Of course you use Google and Wikipedia to broaden your knowledge, but web sources are reliably unreliable, especially when discussing a medium rather older than the internet. Sometimes there’s no alternative to hitting the books.

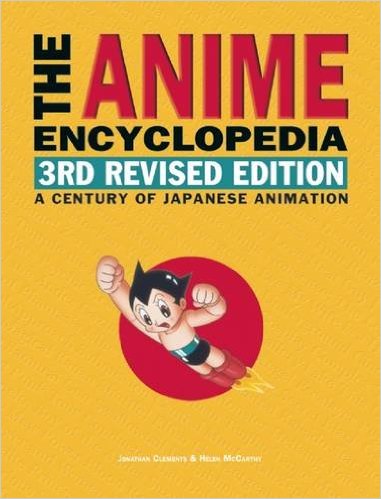

One sturdy book you can hit without leaving a dent is The Anime Encyclopedia, by Jonathan Clements and Helen McCarthy. The first edition was published in 2001, while the third edition came out a year ago, 1,160 pages long. Of course, its most obvious use is to look up anime titles, whether standalone videos or Gundam-sized franchises. You can do this with an internet search engine, but the Encyclopedia entries deliver you pithy packages of story synopses, historical contexts (often cross-referencing to other anime with thematic or production links) and informed critiques.

One sturdy book you can hit without leaving a dent is The Anime Encyclopedia, by Jonathan Clements and Helen McCarthy. The first edition was published in 2001, while the third edition came out a year ago, 1,160 pages long. Of course, its most obvious use is to look up anime titles, whether standalone videos or Gundam-sized franchises. You can do this with an internet search engine, but the Encyclopedia entries deliver you pithy packages of story synopses, historical contexts (often cross-referencing to other anime with thematic or production links) and informed critiques.

It’s the critiques that rub some readers the wrong way, particularly the excoriating ones. The Tenchi Muyo franchise is described as having “the appeal and dogged staying power of a mutant cockroach,” though in fairness the original Tenchi is praised as “witty, funny and charming.” The book emphatically takes sides in heated debates. For example, Haruhi Suzumiya and the K-ON! girls are described as “decoy ducks for the patriarchy” who can “attract and deceive their own kind” (i.e. female fans). Sorry, Kyoto Animation!

If this drives you to rage and rejoinder, then co-author Jonathan Clements describes the Encyclopedia as “an edifice to argue with.” But it’s designed to educate as much as provoke. Scattered through the book are thirty-odd lengthy thematic entries, often looking at neglected sides of anime – for example, entries on Early Anime, Sports Anime and Puppetry and Stop Motion. Others are designed to clear up misconceptions or stop bad practices. In the tradition of Orwell’s writings on good English, the “Argot and Jargon” entry warns against arcane anime terms which journalists love using, because it suggests they know what they’re on about and fans love using because it suggests they speak Japanese.

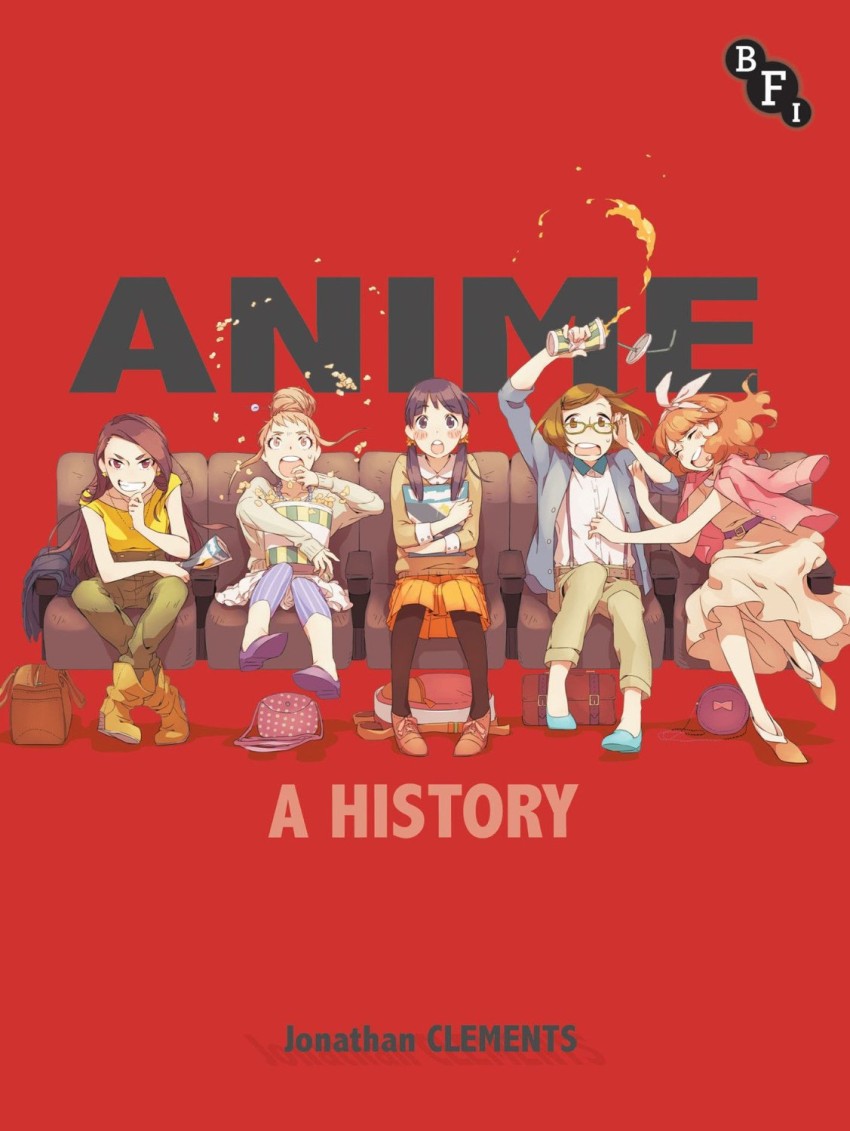

Encyclopedia co-author Jonathan Clements wrote book two on our list, Anime: A History. This is less about anime as a series of individual titles, and more about anime as a century-long industrial process, traced from the first pioneering films circa 1917 to the twenty-first century of Vocaloids and digital downloads. This is a study steeped in history. It’s nearly half the book before we reach Astro Boy in 1963, and only the last third deals with anime after 1980. But if you wondered how anime was deployed in World War II, or how its history twines with the development of Japanese cinema and TV, then it’s indispensable. The back pages contain a massive bibliography of source texts, including many primary ones by anime creators, nearly all in Japanese.

Encyclopedia co-author Jonathan Clements wrote book two on our list, Anime: A History. This is less about anime as a series of individual titles, and more about anime as a century-long industrial process, traced from the first pioneering films circa 1917 to the twenty-first century of Vocaloids and digital downloads. This is a study steeped in history. It’s nearly half the book before we reach Astro Boy in 1963, and only the last third deals with anime after 1980. But if you wondered how anime was deployed in World War II, or how its history twines with the development of Japanese cinema and TV, then it’s indispensable. The back pages contain a massive bibliography of source texts, including many primary ones by anime creators, nearly all in Japanese.

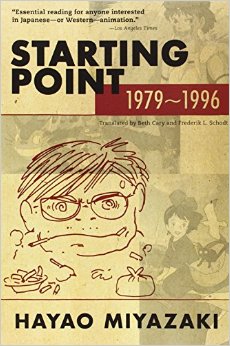

The big exception, and our third book pick, is Starting Point 1979-1996. At 460 pages long, this is a collection of essays, talks, interviews, pitches and occasional doodlings by anime’s most famous creator, Hayao Miyazaki. Translated by Beth Cary and Frederik L. Schodt, Starting Point is a sometimes baffling jigsaw. You might start in the back pages with the detailed timeline of Miyazaki’s life and career, or read it beside Helen McCarthy’s more accessible study, Hayao Miyazaki: Master of Japanese Animation.

With their help, you can start piecing together this artist who presents himself both as a dewy-eyed dreamer and a crusty curmudgeon, who loves and hates the medium he works in. To know the grumpy Miyazaki, read his Starting Point essay “Thoughts on Animation,” where he berates the medium for the stylistic excesses that make many people love it. Then turn to his lyrical essay on running (p37) and read an artist in awed love of human movement.

With their help, you can start piecing together this artist who presents himself both as a dewy-eyed dreamer and a crusty curmudgeon, who loves and hates the medium he works in. To know the grumpy Miyazaki, read his Starting Point essay “Thoughts on Animation,” where he berates the medium for the stylistic excesses that make many people love it. Then turn to his lyrical essay on running (p37) and read an artist in awed love of human movement.

A warning: as the title implies, the book cuts off in 1996, before Princess Mononoke, Spirited Away et al. If you’re specifically interested in them, you need the sequel collection, Turning Point (also in English). This has more of Miyazaki’s thoughts on politics and history, good for analysing Princess Mononoke or The Wind Rises.

Students of Osamu Tezuka, meanwhile, have several books to choose from. The one we’ll highlight as our fourth pick is Toshio Ban’s The Osamu Tezuka Story: A Life in Manga and Anime. It isn’t out yet – Amazon UK currently has the English translation (by Schodt) scheduled for July. It’s a huge manga strip, more than 900 pages long, exploring Tezuka’s career, drawn by a chap who was Tezuka’s employee for more than a decade. The publisher Stone Bridge Press describes the book as a “documentary manga biography.”

There are already book-length studies of Tezuka in English. One of the friendliest is Helen McCarthy’s large-format, lavishly-illustrated The Art of Osamu Tezuka: God of Manga, covering Tezuka’s work in the round. Frederik L. Schodt’s The Astro Boy Essays focuses on one of his most famous creations and Astro’s decades-long career, while Natsu Onoda Power’s God of Comics: Osamu Tezuka and the Creation of Post-World War II Manga concentrates on the comics field. If you’re focusing on how Astro reached America, you need Astro Boy and Anime Come to the Americas. It’s an account of how producer Fred Ladd helped bring Tezuka to the West, written by Ladd with Harvey Deneroff.

There are already book-length studies of Tezuka in English. One of the friendliest is Helen McCarthy’s large-format, lavishly-illustrated The Art of Osamu Tezuka: God of Manga, covering Tezuka’s work in the round. Frederik L. Schodt’s The Astro Boy Essays focuses on one of his most famous creations and Astro’s decades-long career, while Natsu Onoda Power’s God of Comics: Osamu Tezuka and the Creation of Post-World War II Manga concentrates on the comics field. If you’re focusing on how Astro reached America, you need Astro Boy and Anime Come to the Americas. It’s an account of how producer Fred Ladd helped bring Tezuka to the West, written by Ladd with Harvey Deneroff.

Tezuka students should also read Miyazaki’s infamous essay in Starting Point, “I Parted Ways With Osamu Tezuka When I Saw The ‘Hand of God’ in Him.” Written just after Tezuka’s death in 1989, it’s a devastating hatchet job on his anime work. Among other things, it suggests the ‘God of Manga’ beggared anime, creating Astro Boy at rock-bottom prices and setting fatal precedents. This argument is explored in detail in Chapter 6 of Clements’ Anime: A History, which suggests a partial defence of Tezuka’s “warrior” business.

Astro Boy brought anime to the wider world in the 1960s. In the 1990s, though, the same role fell to a yellow rodent with a jagged tail. Our fifth book pick, Pikachu’s Global Adventure, is an anthology of essays edited by Joseph Tobin, looking at how Pokemon went international. It focuses especially on how Pokemon was received by children in different countries, and the adult business of localising and re-versioning it as an international juggernaut. Some fans howl at the book’s claim that the Pokemon craze was soon over, but the craze was indeed short-lived. Pikachu’s Global Adventure focuses on the brief time when Pikachu was massive in the west, while critically-praised films like Perfect Blue and Spirited Away were teeny-tiny cults.

Our next two picks let anime professionals in Japan speak about their work. Ian Condry, author of The Soul of Anime, talks to big names such as master director Mamoru Hosoda and Ghibli president Toshio Suzuki. He drops in on a Gundam toy factory and a recording session at the Gonzo studio. As well as profiling the big names, Condry also discusses much lesser-known titles (ever hear of the pre-school Deko Boko Friends?). The book constructs elaborate models of the creative energy of anime, its “soul,” which sloshes between pros and fans, Japan and the world. But the book is invaluable just as reportage.

Our next two picks let anime professionals in Japan speak about their work. Ian Condry, author of The Soul of Anime, talks to big names such as master director Mamoru Hosoda and Ghibli president Toshio Suzuki. He drops in on a Gundam toy factory and a recording session at the Gonzo studio. As well as profiling the big names, Condry also discusses much lesser-known titles (ever hear of the pre-school Deko Boko Friends?). The book constructs elaborate models of the creative energy of anime, its “soul,” which sloshes between pros and fans, Japan and the world. But the book is invaluable just as reportage.

Our seventh pick is Anime Interviews, lifted from the US magazine Animerica (now sadly folded). Edited by Trish Ledoux, the interviewees include very big fish: Miyazaki, Mamoru Oshii, Masamune Shirow, Rumiko Takahashi, Gundam creator Yoshiyuki Tomino, Macross creator Shoji Kawamori and Harlock creator Leiji Matsumoto. Regarding first-hand accounts, we should also give a shout-out to another book, The Notenki Memoirs. This is a slim but informative account of the history of Studio Gainax, written by co-founder Yasuhiro Takeda. It’s not a history of Evangelion, but rather shows how the studio developed to where Eva became possible. Unfortunately, the book’s hard to find except at hugely inflated prices.

Our pick number eight is Anime: A Critical History by Rayna Denison. Published as part of the “Bloomsbury Film Genres” series, the book explores the complex relationship between anime and genre, and the way genre is used – by marketers, creators, pundits and fans – to understand anime. Denison examines how anime has been written about; the national newspaper journalists reporting the perversions of Overfiend, or the early British fans weighing up the Cute Female Fighters of Dirty Pair and Bubblegum Crisis. But she also explores how the industry generates these perceptions, whether through early TV series or through Ghibli’s creation of its own brand-cum-genre.

Our pick number eight is Anime: A Critical History by Rayna Denison. Published as part of the “Bloomsbury Film Genres” series, the book explores the complex relationship between anime and genre, and the way genre is used – by marketers, creators, pundits and fans – to understand anime. Denison examines how anime has been written about; the national newspaper journalists reporting the perversions of Overfiend, or the early British fans weighing up the Cute Female Fighters of Dirty Pair and Bubblegum Crisis. But she also explores how the industry generates these perceptions, whether through early TV series or through Ghibli’s creation of its own brand-cum-genre.

The ninth book, Frames of Anime by Tze-Yue G. Hu, also blends history and criticism. Like Clements’ Anime: A History, it’s particularly interested in the medium’s early origins and in anime landmarks decades before Akira; titles such as the Momotaro films in World War II and Hakujaden in 1958. Entwined round this history are Hu’s arguments about why animation is so prevalent in Japan, which she links to the circumstances of the country’s modernisation. Hu also reflects on what anime means to Japan’s Asian neighbours (rather than to America or Britain). For instance, the very anime process is postcolonial; it outsources work to those cheap-labour nations that Japan invaded violently in the 1930s and 1940s.

The ninth book, Frames of Anime by Tze-Yue G. Hu, also blends history and criticism. Like Clements’ Anime: A History, it’s particularly interested in the medium’s early origins and in anime landmarks decades before Akira; titles such as the Momotaro films in World War II and Hakujaden in 1958. Entwined round this history are Hu’s arguments about why animation is so prevalent in Japan, which she links to the circumstances of the country’s modernisation. Hu also reflects on what anime means to Japan’s Asian neighbours (rather than to America or Britain). For instance, the very anime process is postcolonial; it outsources work to those cheap-labour nations that Japan invaded violently in the 1930s and 1940s.

The tenth and final book in our list is Anime’s Media Mix by Marc Steinberg. While the other books acknowledge that anime is a cog in a much greater media machine, Steinberg makes this the centre of his discussion. Astro Boy returns; Steinberg calls his anime debut, “a tipping point in the development of transmedia relations in postwar Japanese visual culture.” Astro Boy isn’t a robot, nor fundamentally animated. He’s a dynamically immobile image, migrating from manga to anime, to stickers to lunchboxes. He’s “a new way of selling products and a new way of organising media relations.” Or as Clements quipped in his review of Steinberg’s book, he’s like you-know-who in Ringu, climbing unstoppably out of the you-know-what.

The tenth and final book in our list is Anime’s Media Mix by Marc Steinberg. While the other books acknowledge that anime is a cog in a much greater media machine, Steinberg makes this the centre of his discussion. Astro Boy returns; Steinberg calls his anime debut, “a tipping point in the development of transmedia relations in postwar Japanese visual culture.” Astro Boy isn’t a robot, nor fundamentally animated. He’s a dynamically immobile image, migrating from manga to anime, to stickers to lunchboxes. He’s “a new way of selling products and a new way of organising media relations.” Or as Clements quipped in his review of Steinberg’s book, he’s like you-know-who in Ringu, climbing unstoppably out of the you-know-what.

Andrew Osmond is too polite to mention that he is the author of 100 Animated Feature Films, the BFI Film Classic on Spirited Away and a biography of Satoshi Kon.

To see what our writers think of the ten best books in manga studies… click here.

animation, anime, Anime Studies, book reviews, books, film studies, Japan, recommended reading

Mikhail Koulikov

December 14, 2015 7:06 pm

Great job - and a great list! Very useful. And I really like that you included both academic/scholarly books and more general ones! Though I would have added one of the essay collections, such as "Cinema Anime", just for an introduction to the range of academic writing on anime! ...for what it's worth, I have an almost comprehensive list of English-language books on anime/manga that have been published since 1983 up at http://www.corneredangel.com/amwess/books_amwess.html

Tin

January 20, 2016 5:38 am

Very informative! I'm planning to read some of these. Thanks!