Anime UK Magazine

July 21, 2017 · 3 comments

Chris Perkins on the history of Britain’s first anime magazine.

In 2017, British anime fans wanting to read about their favourite medium are spoiled for choice. Be it print magazines such as Neo, MyM or Otaku USA from across the pond, or one of the numerous online sources, you’ve never had it so good. It wasn’t always this way. Back in the early 1990s, there was very little written about Japanese animation in English at all, leading a group of early fans to get together and do it for themselves.

In 2017, British anime fans wanting to read about their favourite medium are spoiled for choice. Be it print magazines such as Neo, MyM or Otaku USA from across the pond, or one of the numerous online sources, you’ve never had it so good. It wasn’t always this way. Back in the early 1990s, there was very little written about Japanese animation in English at all, leading a group of early fans to get together and do it for themselves.

The magazine was like a Petri dish of new writers: the place that gave figures like Jonathan Clements, Peter J Evans, and James Swallow their first steps in writing about Japanese animation. Without Anime UK, the industry today would be a very different place. Its roots were in the thriving fanzine culture of the pre-digital age. Before virtually anyone could start a website, dedicated fans of every stripe were hard at work producing fan-made zines out of their bedrooms or offices. Anime UK began life as a newsletter, mailed out to a small number of subscribers. It started back in 1990, when Helen McCarthy and Steve Kyte curated an anime programme at the National British SF Convention – believed to be the first such anime event of its kind in the UK. It went down so well that it was clear that there was a potential audience wanting to know more about this anime thing.

“Steve and I set up a newsletter that came out every couple of months,” explains McCarthy. “It was very old tech – typed on an old typewriter, pasted up in our dining room table and photocopied – but it was a huge help in those days when most people didn’t have the Internet.” In this largely pre-internet era the Anime UK newsletter helped bring together early British-based fans and foster a community. “People really loved playing around with the aesthetics of anime and manga and we soon found our newsletter subscribers were artists, writers, costumers – they wanted to express themselves.”

One of those early subscribers was Wil Overton (who would later go on to create art for Future Publishing, Rare and various other gaming companies) who showed it to his boss, Peter Goll. “Peter knew nothing about anime but he thought it looked amazing and loved what we were doing,” McCarthy recalls. “He decided to fund a magazine devoted to it, even though none of us, him included, had any publishing experience. It was mad, but we had no idea just how mad.”

And so, in 1991, Anime UK magazine was born. Helen took the reins as editor, with Kyte and Overton as artists and designers, and Goll as publisher. For the first few years, the bi-monthly magazine could be found in comic shops and specialist retailers, or on subscription. It later relaunched as a newsstand monthly, with better distribution and new numbering.

And so, in 1991, Anime UK magazine was born. Helen took the reins as editor, with Kyte and Overton as artists and designers, and Goll as publisher. For the first few years, the bi-monthly magazine could be found in comic shops and specialist retailers, or on subscription. It later relaunched as a newsstand monthly, with better distribution and new numbering.

The staff took their influences from the Japanese anime magazines like Newtype and Animage that could be found “…on import at hugely inflated prices from a shop called Books Nippon in St Paul’s Churchyard.” These glossy and weighty tomes seemed like the Holy Grail to fans of the time, when information was much harder to come by. Anime UK tried to capture something of the dynamism and excitement of the Japanese monthlies – although budget restrictions meant that it was some time before it was able to go full colour.

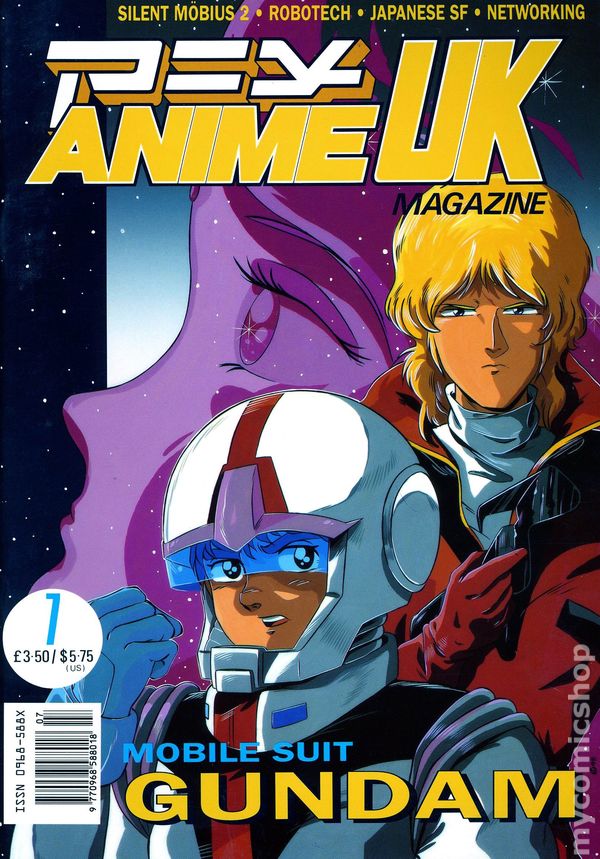

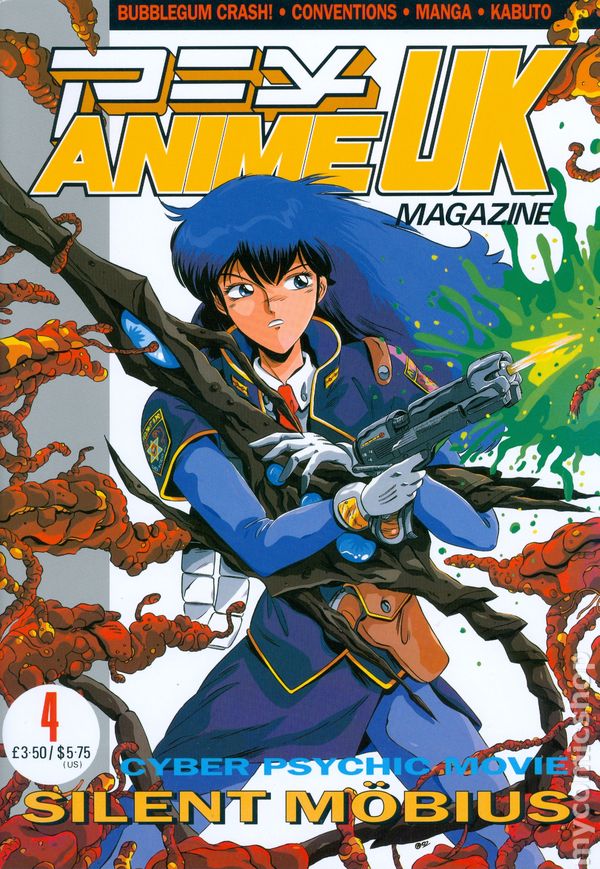

The content of the magazine would be largely familiar to fans today – news, reviews, articles on the latest shows, and convention reports. It also tackled wider Asian pop culture, with coverage of video games, Cantonese and Japanese live-action movies, sentai and Japanese music as well as the expected anime and manga. It also offered in-depth coverage of titles that included character profiles and episode guides – stuff you’d be more likely to find online than in a print title today. Despite having “UK” in its title the magazine had an international feel, with contributors in Japan and the US, and readers worldwide.

“We wanted anime and manga to be transparent to our readers – ‘scrutable’ as one of our posters once put it,” McCarthy explains. “There was so much crap talked about the inscrutable orient and how Japan was inherently other, and we didn’t buy that.” The magazine was very newcomer-friendly, and glossaries and beginner’s guides eased them in. “We knew we loved Japanese culture but it was made by real people, not some weird exotic creatures.”

No mainstream sci-fi or film magazine of its day would feature anime, so for some time Anime UK was the only place you could find it. The magazine also featured coverage of fanzines, fan-art and cosplay long before it was cool. It even had a cookery feature (complete with manga-style illustrations, featuring popular characters of the era, named Ah Oishii (“Ah Delicious”) which became an unexpected favourite with readers.

One way the magazine differed from both its inspiration, and certain successors such as Animerica and Anime Insider was in its editorial stance, which featured a willingness to engage with anime critically. “It was the only way we knew how to work,” says McCarthy. “We loved this stuff but we were all critical fans. We had strong views about all the other stuff we loved – fantasy TV, movies, games, music, books – so we were never likely to treat anime and manga any different than Star Trek or Doctor Who.” Reviews never pulled their punches, and if the writers thought an anime was bad, they weren’t afraid to tell you. This may have won the respect of fans, but it wasn’t always so popular with the distributors, and one even infamously pulled its advertising from the magazine and had McCarthy fired from a column on another magazine.

One way the magazine differed from both its inspiration, and certain successors such as Animerica and Anime Insider was in its editorial stance, which featured a willingness to engage with anime critically. “It was the only way we knew how to work,” says McCarthy. “We loved this stuff but we were all critical fans. We had strong views about all the other stuff we loved – fantasy TV, movies, games, music, books – so we were never likely to treat anime and manga any different than Star Trek or Doctor Who.” Reviews never pulled their punches, and if the writers thought an anime was bad, they weren’t afraid to tell you. This may have won the respect of fans, but it wasn’t always so popular with the distributors, and one even infamously pulled its advertising from the magazine and had McCarthy fired from a column on another magazine.

At one point, the magazine tried to diversify into anime distribution on VHS, with KO Century Beast Warriors, dubbed by a cast that included many of the AUK staff. “We loved the show,” remembers McCarthy, “and Jonathan Clements did a great translation as well as being a terrific voice actor. James Swallow was a revelation as a voice actor, too – he did his role in an American accent and most American viewers found it hard to believe he was actually British.” Not every listener found the dub quite so entertaining – the locally-sourced cast was at least partly caused by the loss of several leading performers just before recording, when their agents objected to appearing in one of those “manga” films. This led to some sadly “amateurish performances” among the leads, and certainly did not help the show’s prospects on the market. It was to be the only release from the new AUK Video label.

The magazine was picked up by Ashdown Publishing in 1995 and rebranded as Anime FX, with a more international perspective. What was hoped to be a glorious new beginning for the magazine instead proved to be the beginning of the end, and the final issue was published in February 1996.Anime UK/FX lasted for barely 30 issues over the space of six years, but formed the foundation for much of the anime- and manga-related journalism that followed, supplying writers, attitude, resources and even vocabulary for successors such as Manga Max and NEO. In those few short years, it played a major part in the coverage of anime in the English language, and the growth of anime in the UK. It even won a coveted Tezuka Award in 1994.

“One of the things that I am happiest about,” observes McCarthy, “is the number of readers who became contributors, and then went on to make their careers in the creative arts. The number of people who told me that AUK influenced them or helped them follow their own dreams is the thing I’m proudest of. Winning the Tezuka Award was really nice – winning awards is always nice – but the impact the magazine had on people is the thing I’m most proud of.”

The industry is undoubtedly a very different place today, but 21 yeas after it folded, could a title like Anime UK make it today? Helen isn’t sure, but would happily give it a shot.

“I don’t know if AUK would survive today but I do know that if I was offered the chance to do it again I would, in a heartbeat. Peter Goll retired and went to run an airbus service in Hawaii, but I’d insist on being allowed to hire [Wil] Overton and [Steve] Kyte again. I think we could make something really beautiful, even in today’s more jaded market.”

Darren Ashmore

July 21, 2017 11:44 am

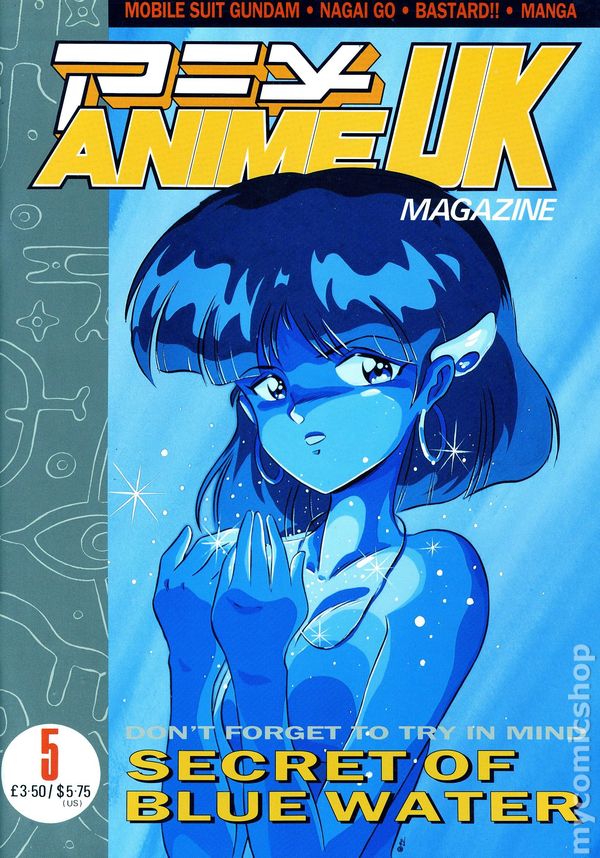

It got me my start, right enough: Issue Five, for the Nadia feature. An innocent time and perhaps rather naive, but a fair one nevertheless.

Carlo Bernhardi

July 22, 2017 11:40 am

With it being mostly a pre-internet era, Newsletters, FanZines, and APAs (Amateur Press associations), were how pen-pals and Fan Clubs made the Information Super Highway of its day, spreading the word, and finding fellow pioneers to create the community. The Transition from Newsletter to glossy magazine was welcomed and supported by the Fandom Community, and in the days when manga was still being discovered black & white was all the rage!! I know my own Anime Fan club (Anime KYO UK) got a boost from being in issue one of Anime UK, and that the printed word be it magazine or photocopy thrived on its contributors, and grow with its readers.

Simon Kempster

January 20, 2024 9:28 pm

Hi Chris, I can add to your story, for a few issues I use to produce the Anime UK magazine, I did the Repro and looked after the printing and finishing of the magazine. I, my father and Peter Goll from Sigma funded and kept the magazine going for a while. If you are interested in knowing more, please do get in touch. Thanks Simon