Books: Miyazaki’s Animism Abroad

June 14, 2016 · 0 comments

By Andrew Osmond.

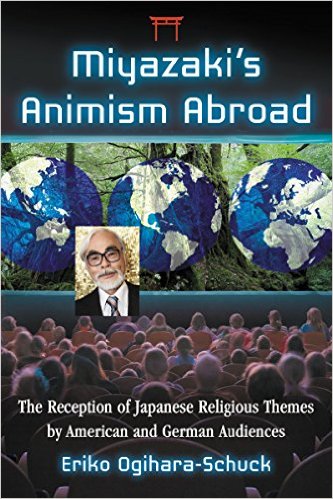

Miyazaki’s Animism Abroad is an academic study by Eriko Ogihara-Schuck, subtitled The Reception of Japanese Religious Themes by American and German Audiences. It’s a very niche book, mainly for readers with specific interests in anime’s treatment of religion and spirituality: how anime is translated/adapted when it travels to other cultures; and how it’s received by those cultures. However, it contains one chapter of much greater interest to Miyazaki fans. Ironically, it’s not about how Miyazaki’s work was received abroad, but about how it was received in Japan, with plenty of eye-openers.

Miyazaki’s Animism Abroad is an academic study by Eriko Ogihara-Schuck, subtitled The Reception of Japanese Religious Themes by American and German Audiences. It’s a very niche book, mainly for readers with specific interests in anime’s treatment of religion and spirituality: how anime is translated/adapted when it travels to other cultures; and how it’s received by those cultures. However, it contains one chapter of much greater interest to Miyazaki fans. Ironically, it’s not about how Miyazaki’s work was received abroad, but about how it was received in Japan, with plenty of eye-openers.

Animism, as Ogihara-Schuck explains in the opening pages, “is a belief system that recognises gods and spirits in animate and inanimate objects.” It’s not unique to Japan; think of the Dryads in Greek myth, which are tree spirits like the Kodama in Japan (presented as rattle-headed humanoids in Princess Mononoke). Nonetheless, animism has a particularly strong tradition in Japan through the centuries-old traditions called Shinto. There are complications with the “Shinto” label, as indeed there are with calling Shinto a religion. Even “animism” raises issues; the word was coined by a Victorian anthropologist in a book called Primitive Cultures, though it’s now often used by Japanese commentators.

As one would expect in an academic book, Ogihara-Schuck spends a long time talking through these issues, noting they concern Miyazaki himself. The director presents artefacts connected with Shinto in his films – for example, Totoro has a woodland shrine and a rope (a “Shimenawa,” made of rice paper) around Totoro’s tree. However, Miyazaki calls his work “animist” rather than “Shinto,” describing animism as a religious mentality rather than a religion. In a telling comment, he says that kami, gods or spirits, are “deep in the mountains and valleys rather than in glittering shrines.” This supports Helen McCarthy’s analysis of Totoro in her pioneering book, Hayao Miyazaki: Master of Japanese Animation, where she argues, “Religion is a human construct… Nature spirits live outside it.”

As Ogihara-Schuck’s “Animism Challenges Monotheism” chapter makes clear, many other Japanese people responded to Miyazaki’s treatment of animism. His films drew the attention of what she calls spiritual intellectuals: “scholars of philosophy, religion and psychology who have extensively appeared in mass media to discuss indigenous Japanese religions as the core of Japanese cultural identity.” Miyazaki is acquainted with some of these celeb thinkers, including Takeshi Umehara and Tetsuo Yamaori. The book Turning Point includes a talk between Miyazaki and Yamaori, discussing animism, monotheism… and the 9/11 attacks.

Many of these discussions are controversial, to put it mildly. For example, Miyazaki and Yamaori suggest that 9/11 resulted from the aggression of Western monotheism, which should take lessons from the more peaceable gods of Japan. This could be seen as outrageous, given Japan’s twentieth-century crimes in the name of Shinto… though Miyazaki, Umehara and Yamaori condemn these as state-manufactured abominations. Umehara and Yamaori were forthright critics of the notorious Prime Minister Yoshiro Mori, who claimed in 2000 that “Japan is the land of god(s) with its emperor at the centre.”

Many of these discussions are controversial, to put it mildly. For example, Miyazaki and Yamaori suggest that 9/11 resulted from the aggression of Western monotheism, which should take lessons from the more peaceable gods of Japan. This could be seen as outrageous, given Japan’s twentieth-century crimes in the name of Shinto… though Miyazaki, Umehara and Yamaori condemn these as state-manufactured abominations. Umehara and Yamaori were forthright critics of the notorious Prime Minister Yoshiro Mori, who claimed in 2000 that “Japan is the land of god(s) with its emperor at the centre.”

This part of the discussion is fascinating enough, before Ogihara-Schuck moves on to recount how other Japanese pundits brought Miyazaki into current affairs. Tetsuya Chikushi, a famous news anchorman, claimed the post-9/11 world could be elucidated by contrasting the world-views of two fantasies: Miyazaki’s polytheist Spirited Away versus the monotheist Harry Potter. That was nothing, though, beside a story printed by the Asahi Shimbun paper on New Year’s Day 2003. Headed “In the Spirit of Sen and Chihiro,” the story suggested that Japan look to its polytheist roots, and be calm and flexible like Spirited Away’s Chihiro… in its dealings with North Korea.

The story was published soon after Kim Jong-il admitted his country had kidnapped Japanese civilians. The chief author of the article later said the “Sen and Chihiro” title was consciously used to attract attention. There was, not surprisingly, a backlash. One critic of the story was a politician, Shinzo Abe (now Japan’s Prime Minister), who decried the offensive linking of a tragic situation to a cartoon. Taking a broader perspective, Katsuhiro Ohara, a Japanese Christian priest, argued the adoration of polytheism was an inverted Orientalism, by a country still seeking an identity.

Ogihara–Schuck goes on to note how Miyazaki’s films have been referenced more recently in Japan. For example, Spirited Away’s closing song (“Always With Me”) was performed on television by a former Chernobyl evacuee; the performance was shown on 6th August, commemorating the Hiroshima bombing. When the Fukushima plant went into meltdown in 2011, a party leader (Mizuho Fukushima of the SDP) tweeted it was like the God Warrior in Nausicaa. Ogihara-Schuck cites many other examples.

Ogihara–Schuck goes on to note how Miyazaki’s films have been referenced more recently in Japan. For example, Spirited Away’s closing song (“Always With Me”) was performed on television by a former Chernobyl evacuee; the performance was shown on 6th August, commemorating the Hiroshima bombing. When the Fukushima plant went into meltdown in 2011, a party leader (Mizuho Fukushima of the SDP) tweeted it was like the God Warrior in Nausicaa. Ogihara-Schuck cites many other examples.

For readers fascinated – like me – with these subjects, the chapter should be read in conjunction with the books Starting Point and Turning Point, which this blog has recommended. Unfortunately, this brings up a serious limitation: Ogihara-Schuck refers extensively to Starting Point and Turning Point, but cites the Japanese editions of the books, not the English translations available from Viz Media. In fairness, Ogihara-Schuck’s book was published in 2014, the same year as the translated Turning Point, so she probably couldn’t cross-reference it. But it’s bizarre that she doesn’t acknowledge the translated Starting Point, which has been on sale since 2009.

For the record, the most important cross-references include a conversation from page 356 to 359 in the English Starting Point, where Miyazaki waxes lyrical about a “broadleaf evergreen forest culture,” underpinning his view of Japan. The other relevant conversations are in Turning Point, where Miyazaki has a long talk with Umehara about animism and Princess Mononoke, starting on page 94. Miyazaki’s controversial comments on 9/11 are in a talk with Chikushi from page 231, and in the talk with Yamaori (mentioned above) from page 244. There are some particularly juicy quotes on pages 253 to 254, where Miyazaki opines: “As an East Asian aboriginal, (I) want to have Bush and Bin Laden duke it out together to settle things.”

As mentioned earlier, the reactions to Miyazaki’s animism in Japan are only a small part of Ogihara-Schuck’s book. However, I found it by far the most interesting section. That’s not to say the rest isn’t interesting too, but it focuses on a niche subject at such length that it’s sometimes numbing. That subject is given in the book’s subtitle: the reception of Japanese religious themes by American and German audiences.

As mentioned earlier, the reactions to Miyazaki’s animism in Japan are only a small part of Ogihara-Schuck’s book. However, I found it by far the most interesting section. That’s not to say the rest isn’t interesting too, but it focuses on a niche subject at such length that it’s sometimes numbing. That subject is given in the book’s subtitle: the reception of Japanese religious themes by American and German audiences.

“Miyazaki’s films have established themselves as regular fixtures in American and German popular culture since Spirited Away,” Ogihara-Schuck writes. “Did Miyazaki’s films become widely known because religion did not matter in films that are fantasies made for the purposes of entertainment? Or did religion actually matter? If so, how did two nations with Christian majorities receive and engage with the films’ foreign religious elements?”

Ogihara-Schuck seems cavalier with phrases like “widely known” and “regular fixtures,” but they’re defensible. When I checked the American Amazon.com site, it ranked the Spirited Away DVD at #342 in “Movies & TV”, higher than I expected. Totoro was higher still at #160. Miyazaki films are in Amazon’s top hundred “Kids and Family” titles, above big cartoons from Pixar, DreamWorks and Disney. In contrast, the excellent non-Miyazaki Wolf Children barely breaks the top 2500 movies, and doesn’t make the top 500 “Kids and Family.”

The book proceeds by looking at how five of Miyazaki’s most animist films were adapted in America and Germany: Nausicaa, Totoro, Princess Mononoke, Spirited Away and Ponyo. (Miyazaki’s Laputa has powerful animist imagery, but it’s reflected less overtly in the script, and viewers may miss it behind the steampunk.) Ogihara-Schuck goes through Warriors of the Wind (the 1980s abridgement of Nausicaa); the Carl Macek version of Totoro in 1993; the Miramax (now Disney) Princess Mononoke; and the Disney versions of Spirited Away, Nausicaa, Totoro and Ponyo.

First, Ogihara-Schuck goes through the adaptations themselves, starting with the English ones. She notes various changes that, arguably, downplay the film’s animist worldview and, also arguably, make them more accessible to Christian cultures. For example, Miyazaki is well-known for not making straightforwardly “evil” characters, even when they initially seem monstrous – examples include Nausicaa’s Ohmu insects, and Yubaba and No-Face in Spirited Away. Ogihara-Schuck picks out instances when the adapted scripts seem to demonise or dehumanise the characters, against the ethos of the original film.

I noticed one case of this myself. In Spirited Away, one of the supporting characters is a non-human woman, Lin, who helps the girl Chihiro. At one point, the Disney dub adds a gratuitous comment that Lin would not “recognise” love, apparently because that’s a human thing.

At first this discussion is engaging enough, even though these kind of arguments waver between subtle and picky. Some examples seem very picky, though the intention is clearly to assemble a list of minor changes pointing to larger trends. For instance, the Catbus doesn’t speak in the Japanese Totoro. It does in the Carl Macek dub (with Macek’s own voice). But does this really show that animism must be tamed, made more anthropomorphic, for the American market? In Macek’s version, the dubbed Catbus says the name of its ‘next stops,’ written in Japanese on its head. Macek just disliked the alternative solution, which would have been to use subtitles in a children’s film.

Ogihara-Schuck also makes heavy weather over other small changes, like Disney’s Nausicaa addressing an insect as “good boy” rather than “good child”; or the Miramax Mononoke script referring to the most powerful animist being as a “spirit” rather than a “god.” She is unconvinced by Mononoke adapter Neil Gaiman’s comment that “Great Spirit of the Forest” sounds better than, for example, “Deer God” or “Forest God.”

Ogihara-Schuck also makes heavy weather over other small changes, like Disney’s Nausicaa addressing an insect as “good boy” rather than “good child”; or the Miramax Mononoke script referring to the most powerful animist being as a “spirit” rather than a “god.” She is unconvinced by Mononoke adapter Neil Gaiman’s comment that “Great Spirit of the Forest” sounds better than, for example, “Deer God” or “Forest God.”

In that case, I sided with Gaiman; but I still found many of Ogihara-Schuck’s points useful. For example, there’s a handy discussion (pp.92-3) of the different Japanese words for magic. The Shinto kind (“majinai”) has far more everyday connotations, largely lost in Western translations. Interestingly, though, Kiki’s in Kiki’s Delivery Service is referred to as “maho”; that’s a Westernised word for magic, coined in the nineteenth century.

The book carries on through the American Miyazaki adaptations, then the German adaptations, then the American reviews and German reviews of the films and the American Christian reviews and German Christian reviews. I confess my eyes glazed in the later chapters. At times, it feels like the arguments might read better in table form, as the author diligently counts instances of “evil,” “gods,” “magic” and the like through different adaptations.

There are still some provocative arguments here and there, though – for example, a suggestion (p.187) that American Christian reviewers respond to Miyazaki’s anime differently from German Christian critics, because German churches are less focused on winning converts. And there are useful nuggets of secular info, like the German cinema release of Spirited Away being marketed much more specifically to children by Universum Film than Disney had done in America. Spirited Away’s German title was Chihiro’s Reise ins Zauberland, or Chihiro’s Journey to a Magical World.

I found myself, though, increasingly wondering whether animism is so “non-Western” anyway. The early Hollywood Fleischer cartoons were full of objects with souls, as was the first British stop-motion animation. Disney’s Bambi, decades before Totoro, is full of animist atmosphere, placed outside a fantastical context. Fantasia’s “Nutcracker” sequence is an all-out animist celebration; it was remade with Mononoke imagery as the dazzling “Firebird” sequence in Fantasia 2000. And isn’t the world’s most famous animist teacher a Hollywood creation: Yoda?

I found myself, though, increasingly wondering whether animism is so “non-Western” anyway. The early Hollywood Fleischer cartoons were full of objects with souls, as was the first British stop-motion animation. Disney’s Bambi, decades before Totoro, is full of animist atmosphere, placed outside a fantastical context. Fantasia’s “Nutcracker” sequence is an all-out animist celebration; it was remade with Mononoke imagery as the dazzling “Firebird” sequence in Fantasia 2000. And isn’t the world’s most famous animist teacher a Hollywood creation: Yoda?

As noted earlier, Miyazaki’s Animism Abroad may have rewards for Miyazaki fans with a special interest in intercultural adaptation. The book also has one outstanding chapter that should fascinate Miyazaki fans in general. But readers may find the other chapters hard-going, not for any lack of clarity in the writing, but because they’re so closely argued that they can seem more myopic than enlightening.

Andrew Osmond is the author of the BFI Modern Classic volume on Miyazaki’s Spirited Away.

anime, animism, books, Disney, Germany, Hayao Miyazaki, Japan, religion, Spirited Away, Studio Ghibli

Leave a Reply