Fullmetal Alchemist

October 6, 2016 · 0 comments

By Andrew Osmond.

Whether they’re from the east or west, animation studios know you can’t beat a good mascot. It could be a giant mouse, a plasticine dog, or a box-shaped robot trash compactor. It’s the same story in Japan. Studio Ghibli has Totoro; Production I.G. has the cyber-warrior Kusanagi; Gainax has the Evangelion.

Whether they’re from the east or west, animation studios know you can’t beat a good mascot. It could be a giant mouse, a plasticine dog, or a box-shaped robot trash compactor. It’s the same story in Japan. Studio Ghibli has Totoro; Production I.G. has the cyber-warrior Kusanagi; Gainax has the Evangelion.

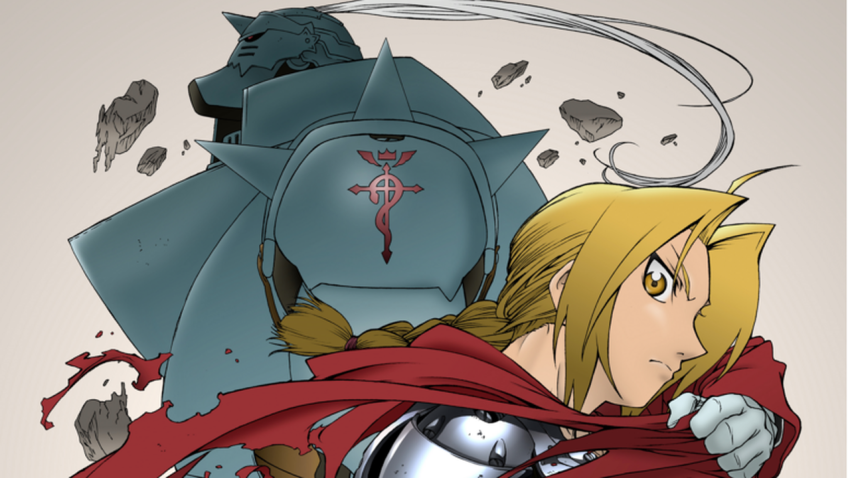

The Bones studio, meanwhile, has two of the best-loved anime characters of all. They’re two brothers, a short-statured chap in a red cloak, and a looming but oddly gentle-looking suit of armour. There’s a hint of Asterix and Obelix about them, though their story is more high tragedy than punch-up farce.

Okay, Bones didn’t create Edward and Alphonse Elric. That was the manga artist Hiromu Arakawa. It was she that wrote the nine-year, twenty-seven book manga about the brothers’ journey through an increasingly rich world of steampunk and sorcery. But the Bones studio was more than an animator-for-hire. Its Alchemist serial, made in 2003, overtook the strip and had to make up its own story. It’s as if Warner Brothers invented Harry Potter’s last adventures when Rowling fell behind.

If you don’t know the Fullmetal Alchemist story, it has the appeal of an unfolding text. It starts simply, a dark fable in an old-fashioned storybook world. As children, Edward and Al are devastated by the sudden death of their beloved mother. They dare to perform a forbidden rite to bring her back, and… terrible things happen. Edward loses an arm and leg, and has to have them replaced, Tin Man-style, with metal limbs. Al, the younger brother, is cursed even more – he loses his whole body, becoming a ghost animating a suit of armour.

If you don’t know the Fullmetal Alchemist story, it has the appeal of an unfolding text. It starts simply, a dark fable in an old-fashioned storybook world. As children, Edward and Al are devastated by the sudden death of their beloved mother. They dare to perform a forbidden rite to bring her back, and… terrible things happen. Edward loses an arm and leg, and has to have them replaced, Tin Man-style, with metal limbs. Al, the younger brother, is cursed even more – he loses his whole body, becoming a ghost animating a suit of armour.

Just in the first few episodes, you’ll sense a big story being seeded. Edward and Al join their world’s military, determined to find a way to fix their cursed condition. Several early episodes are standalone adventures, as the brothers contend with false prophets and killer zombies, but there are bigger plots in play. Who are the monstrous strangers smirking from the shadows, known as the “homunculi”? What is the history of this world, hinted through references to a terrible war, and a giant scarred vigilante killer who could snap any Batman in two? What was the power that maimed the brothers, and – on a personal note – where’s their missing dad?

The Alchemist world builds in tandem with the story. It’s a place where people draw circles on the ground to manipulate the world through alchemy, often in order to fight using stone, steel, or fire. However, the alchemists see their power as science, not magic. One of the fundamental principles is that an alchemist can only transmute matter between forms that share basic properties – mass, for instance. Something, some form of matter, must be destroyed for another to be constructed. Or as Edward puts it, “To obtain, something of equal value must be lost.” This is the Law of Equivalent Exchange, paralleling the real first law of thermodynamics.

Alchemist’s setting is a land of steam trains and telephone kiosks – the latter the stage for one of Alchemist’s most infamous scenes – and a blue-coated military who serve a kindly-seeming king… with the title of Fuhrer. There are hints of alternate history – and of steampunk – Edward’s artificial limbs are the product of a technology called “automail,” a kind of cybernetics that could fit into a Jules Verne yarn. And like the best steampunk, Alchemist resonates with the real world and pervasive moral uncertainties about the “glories” of history.

Alchemist’s setting is a land of steam trains and telephone kiosks – the latter the stage for one of Alchemist’s most infamous scenes – and a blue-coated military who serve a kindly-seeming king… with the title of Fuhrer. There are hints of alternate history – and of steampunk – Edward’s artificial limbs are the product of a technology called “automail,” a kind of cybernetics that could fit into a Jules Verne yarn. And like the best steampunk, Alchemist resonates with the real world and pervasive moral uncertainties about the “glories” of history.

And don’t forget the brothers themselves. Edward and Al, already cursed for their hubris, are now signed up as “dogs of the military” – one bad choice piled on another? In putting the gentle Al and the chronically peppery Edward at the show’s heart, Alchemist sidesteps the obvious templates for an epic – a show based around a ‘chosen one’ surrogate for the viewer, or else based around a love story. Instead, this is an odd couple drama, with two siblings tied to each other, sometimes maddened by each other… yet united by oaths and experiences that are terrifying. Alchemist is a story of children who’ve been damaged, not by some external evil, but by their own actions. Thanks to their altered bodies, they must live with those actions every second of their lives.

Interviewed in 2006 by the magazine Newtype USA, Arakawa said, “Most of the problems the characters face, from life-or-death decisions to painful regrets, were things that either came from my own personal experience, or everyday conversations with various people from all walks of life.” Those people included war veterans, refugees and paraplegics – all types that play big parts in Alchemist’s story.

Arakawa hails from Japan’s north island Hokkaido, and said that elements of Alchemist – in particular, the sufferings of a nation called Ishval or Ishbal – were influenced by the history of the Ainu, the indigenous people of Japan. “My ancestors were farmers and homesteaders who displaced Ainu and stole their land from them,” said Arakawa. “But ironically enough, some of my own relatives have Ainu blood in them.”

In anime, Fullmetal Alchemist helped make the name of Studio Bones. The company had been founded in 1998 by employees of the Sunrise studio (Gundam). Bones’ other early shows includes RahXephon (a mecha show for the post-Eva generation), Wolf’s Rain (apocalyptic fantasy) and Scrapped Princess (heroic fantasy). Then one of Bones’ artists, Yoshiyuki Ito, happened on the Fullmetal Alchemist manga loved it, and recommended it to the studio’s co-founder, Masahiko Minami. When the anime was made, Ito would adapt Arakawa’s designs for the series, and provide key Alchemist animation.

“When we started the series, the manga was still in the early stages and the pacing was not yet determined,” Minami told me in an interview. “So we made the animation with the premise that original elements would be included from the beginning.” If you read the manga beside the early episodes, you’ll see it’s often faithful to the strip, but with some striking differences. Characters who die quickly in the manga stay alive in the anime, and vice versa. The second half of the series diverges completely; it was made when Bones had run out of manga to adapt, and had to create its own storyline.

Most of the later anime episodes are credited to writer Shou Aikawa, who wrote more than half the show. “The on-air time (of the Japanese broadcast) was fixed,” Aikawa told Anime News Network. “It was not late-night, it was in the evening, so not only older audiences but younger people were going to watch it.” (The Japanese timeslot varied around 5.30 and 6.) “So there was a mission for Studio Bones, Seiji Mizushima and myself, that we have to provide good entertainment for a major audience… concluded in one year. We thought, ‘How can we do this?’ It was all about the development of characters. And that’s why the original parts (of the series) were created.”

For her part, Arakawa actually requested that the anime should have a different ending from her manga. “I left the adaptation completely up to (the Bones staff),” the writer told Newtype USA. “Manga and anime are different modes of expression, and different artists are involved. There’s little point in having a cross-media story if everything is exactly the same in all versions. As I watched the show, I found it very interesting to speculate about what kind of final showdown each of the homunculi would have with the people who spawned them.”

For Western fans in Britain and America, Fullmetal Alchemist was a landmark series. It combined light humour with heavy drama, sometimes very heavy. The shocking “Nina” storyline early in the series was an object lesson is how dark the story could go. Whereas Cowboy Bebop had set the standards for adult themes and characters in a weekly anime, Fullmetal Alchemist offered other things as well; an epic ongoing story and provocatively woven world-building. In Japan, the anime topped one 2005 poll for best TV animation and scored high in another. In America it was shown on Cartoon Network’s Adult Swim, while in Britain it was one of the first long anime series to be serialised on DVD.

Younger fans may know the title through its later anime remake, Fullmetal Alchemist: Brotherhood (also by Bones) which kept closer to Arakawa’s storyline as the manga finally ended in 2010. All the franchise’s principals have since moved on. Arakawa is currently adapting The Heroic Legend of Arslan novels by Yoshiki Tanaka, and her manga forms the basis of the ongoing anime version. Over at Bones, Seiji Mizushima, Sho Aikawa and Yoshiyuki Ito have reteamed for the meta-superhero show Concrete Revolutio. But as Anime Limited brings a new edition of Fullmetal Alchemist to Blu-ray and DVD, now’s the chance to relive their breakout work… and for some readers, the chance to take the journey the first time.

Fullmetal Alchemist is being rereleased in the UK by Anime Limited.

Leave a Reply