Interview: Takashi Nakamura

July 7, 2017 · 0 comments

By Andrew Osmond.

Takashi Nakamura has worked in the anime industry for more than three decades, starting as an animator before moving into direction. Younger fans may know him as co-director (with Michael Arias) of the shocking, cerebral science-fiction film Harmony. But long before that, Nakamura was Animation Director on Katsuhiro Otomo’s iconic Akira, and animated on other 1980s landmarks like Nausicaa and Mysterious Cities of Gold. Since then, his film director credits have ranged across the board. from Catnapped to A Tree of Palme.

Takashi Nakamura has worked in the anime industry for more than three decades, starting as an animator before moving into direction. Younger fans may know him as co-director (with Michael Arias) of the shocking, cerebral science-fiction film Harmony. But long before that, Nakamura was Animation Director on Katsuhiro Otomo’s iconic Akira, and animated on other 1980s landmarks like Nausicaa and Mysterious Cities of Gold. Since then, his film director credits have ranged across the board. from Catnapped to A Tree of Palme.

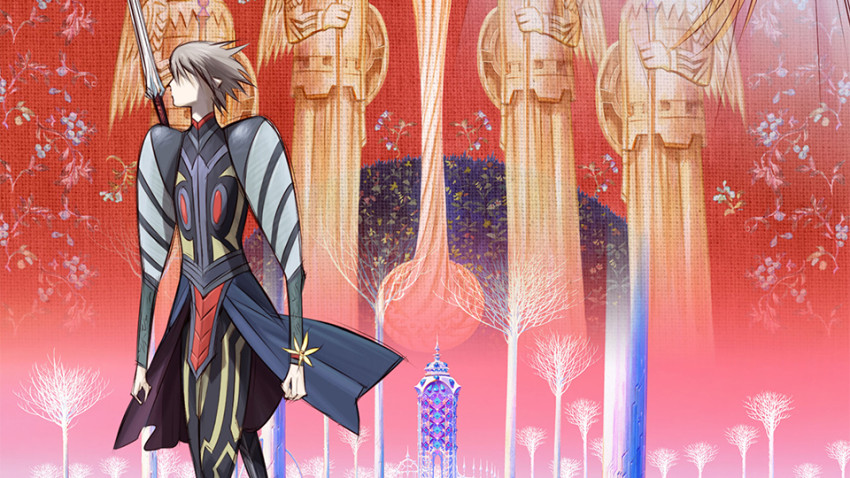

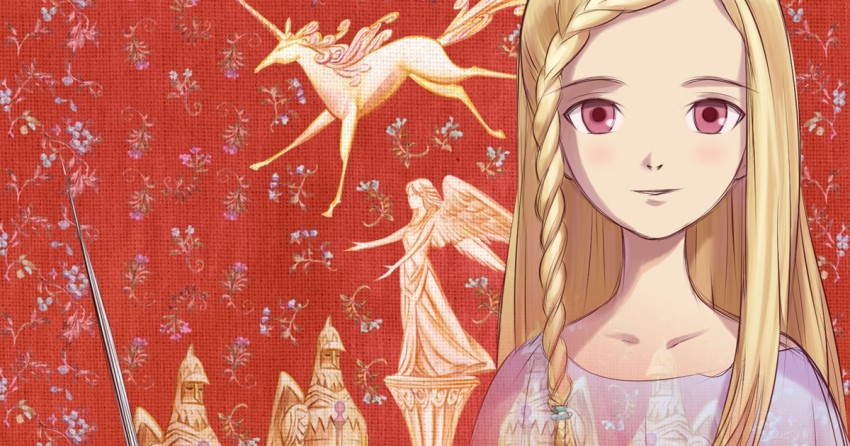

As Nakamura visited Edinburgh to screen his latest work, a CGI short film called Ylion and Callysia, I took the opportunity to quiz him on his career.

Hello Mr Nakamura, thank you very much for talking to us today. You’ve worked on an extraordinary range of anime over several decades. As an animator, you seem to have often created awesome action images. How did you develop such a talent for this kind of image? Was it mostly instinct, or were you always studying the work of other animators and manga artists to improve your images?

Yes, I do research animation, like Disney, Fleischer, these past masters. I am influenced by these great movies, technically speaking. Also I like movies, I watch lots of movies. But I think research is a bit too much for me… For example, with Akira and Nausicaa, both those films’ directors had their own ideas and images, so as an animator I had to go with them rather than be “me” too much. The directors had a really vivid, clear image about what they wanted to do. Yes, I do “research”, kind of, but it’s more like I’m trying to become technically better, all the time.

An important talent for an animator is to be able to create actions that wouldn’t happen in real life, and to make them real.

I wanted to ask about some of the anime you worked on in the 1980s. Do you have any memories of Miyazaki’s Nausicaa? For example, do you remember it as being an especially stressful production, or was it just normal for anime?

I wanted to ask about some of the anime you worked on in the 1980s. Do you have any memories of Miyazaki’s Nausicaa? For example, do you remember it as being an especially stressful production, or was it just normal for anime?

Yes, it was stressful, but it was great to be involved in it. I think any animator would want to work with Miyazaki at least once, it’s something they kind of aspire to, for an experience. He’s actually quite picky about who he would want to work with. He really is a very attractive, interesting, great person. Looking back, Nausicaa is a great work, so it was wonderful to be able to experience it, to be involved in it.

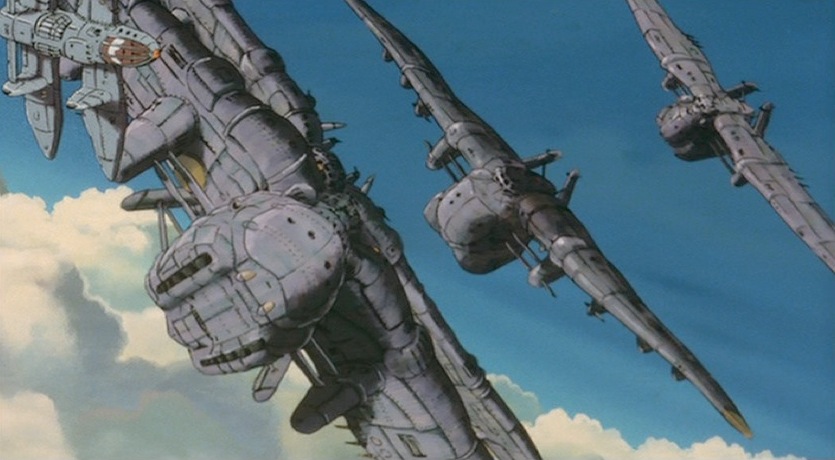

According to one website, you animated a scene in Nausicaa when an airship breaks out of a huge cloud and chases Nausicaa through the sky, firing at her. I thought it was an amazing image. When you are creating that kind of scene, how much of it comes out of research – for example, researching aeroplane battles – and how much does it depend on having a good visual imagination?

Yes, I did that scene where Nausicaa is rescued by the gunship and taken back to the valley. But the answer to your question is basically no. I don’t think many animators actually do that – I don’t think they would try to find footage of explosions, for example, in order to create an explosion. Some animators might try to do something similar to live-action, so they might get some footage of a real explosion. But as far as Nausicaa is concerned, that didn’t happen at all. Pretty much everything is my imagination, based on my own experience and movies I saw in the past, things just coming out of my head. It’s about my inspiration and imagination.

We didn’t really use any references, not in Akira either, or even for CG anime. We don’t have the budget or time, and Miyazaki especially would have hated it if we’d done that. Use imagination, not research material, that’s what he would say. Disney did great research – for example, the animators studied real deer for Bambi. I read about how deep their research was, and I’m envious in a way, but I sort of feel it’s restrictive, because you can’t really use your imagination, you have to follow reality. It just can never happen in Japan, it’s expensive…

I think what’s very interesting and unique about Japanese animation is that we’re on a pretty low budget, but we have to create good work. I think that’s where we can hone our skills and talents, it’s like a philosophy. We use our imagination, and in a way we have more creative freedom, because we’re not restricted to being realistic.

You worked on Akira, which still looks incredible today. When you were working on it, did it feel like it was going to be a special film?

You worked on Akira, which still looks incredible today. When you were working on it, did it feel like it was going to be a special film?

Otomo directed it after he’d previously worked on Harmagedon. When he decided to direct an animated movie, everyone really went “wow” – the anticipation and expectation was so high, and that included the expectations of professional animators. We really wanted to see what this was going to be.

The movement on Akira is painstakingly detailed and intricate, far more than other anime. Can you say why the film took this approach, and how difficult was it to achieve?

It was hard because of the sheer volume of work was massive…Yes, even adding one line makes it more difficult. We didn’t really think about it, we just had to work hard, because Otomo has got this worldview in a movie. He knows what he wants, which is very complicated and multi-layered. He’s very detail-orientated, so we just had to do what he asked us to do and more… That was all we were thinking about.

Akira is pretty much SF; I think if Akira had been American, probably it would have been made in live-action. But we just don’t have budget to make elaborate SF movies, so that’s why we tend to go for animation. That’s quite a Japanese thing, I think, to go for animation on this budget…

Of the scenes in Akira that you worked on, which ones are you most proud of?

I personally like the teddy bear scene where Tetsuo is sleeping and he hallucinates a teddy bear [which attacks him], and that’s very, very Otomo.

Mr Otomo mostly works in manga, not anime. What were your impressions of him as a director on Akira?

There are so many anime based on manga, but it’s rare that the author directs his own movie. It was a great experience to witness his passion and enthusiasm about his own work. Otomo loves his manga, so I think his attitude was that he wanted to see everything through; he did this manga, Akira, and he really wanted to create the anime version as he wanted. I say he’s really responsible for his own work. I think that’s what great about Otomo, he wanted to see it through and he created a great work of art.

Also in the 1980s, you reportedly worked on the TV series The Mysterious Cities of Gold, which many British people still remember today. That was a co-production between Japan and France. Did the fact that it was a co-production make working on it more complicated?

I was only involved as an animator, so I didn’t know the collaborative side of it. But what happened was that when there’s a collaboration between Japan and other countries, (the foreign partners) wanted full animation, whereas in Japan limited animation was more common. But I had always wanted to do full animation, like Disney, so it was interesting and I was really excited about it.

Later you began to write and direct your own anime. Did you always aim to become a director, or did you decide to become a director because you felt restricted in your creative freedom as an animator?

Not really. I didn’t aspire to be a director, but I liked manga, and I liked telling stories. I was an animator for a long time, but I think as I went along, I had stories that I wanted to tell, and how do I do that? – I would have to direct them myself. So it was more like a result than my aspiration. I think I was really fortunate to be in an environment where that happens, but it wasn’t my plan.

The films that you have written and directed all seem very different from each other. You’ve done everything from funny family comedies like Catnapped to the shockingly bleak science-fiction of Harmony. Is this just accidental, or do you prefer to do something very different each time that you direct?

The films that you have written and directed all seem very different from each other. You’ve done everything from funny family comedies like Catnapped to the shockingly bleak science-fiction of Harmony. Is this just accidental, or do you prefer to do something very different each time that you direct?

No, I don’t really think like that; it’s more that it happened that way. For example, with Catnapped, I wanted to make a movie for children, so I did; and Harmony just landed in my lap, so I did it. Harmony is bleak, but it had really good drama and characters, so I wanted to do it.

A lot of Western critics have compared your film A Tree of Palme to the Pinocchio story, while the film’s strange world reminded me a little of Nausicaa. When you created the film, what kind of ideas and intentions did you have in your mind yourself?

I was influenced by Fantastic Planet, and also Pinocchio, I wanted to put in that aspect of spiritual growth. A Tree of Palme is a story for children, but with a stronger philosophy in the background – that’s what I wanted to make.

Your new short film Ylion and Callysia is made in 3D animation, with no dialogue. Did you start with the intention of making a 3D film first and then think of a story, or did you create the story first and then decide it was suited to 3D animation?

The 3D came first. I had to make a short movie in 3D, and then I came up with the story. It was inspired by a French tapestry, The Lady and the Unicorn. I really love the tapestry, it’s really beautiful and I just wanted to create a film version of it. [The medieval tapestry also influenced the look of Disney’s ornate animated film of Sleeping Beauty. The tapestry itself is a story element in the SF anime Gundam Unicorn.]

Because Ylion and Callysia is a short film, I wanted to keep everything simple and also abstract, a little vague. It’s nice to have some ambiguity, so the audience can think about it. The film is short, so I wanted to keep it simple, to keep the atmosphere going, so in a way dialogue would be obstructive. If the characters speak, you would have to explain ‘Why?’ and ‘How?’ and that would expand the movie. So I really thought the less the better, and I used music to tell the story.

Because Ylion and Callysia is a short film, I wanted to keep everything simple and also abstract, a little vague. It’s nice to have some ambiguity, so the audience can think about it. The film is short, so I wanted to keep it simple, to keep the atmosphere going, so in a way dialogue would be obstructive. If the characters speak, you would have to explain ‘Why?’ and ‘How?’ and that would expand the movie. So I really thought the less the better, and I used music to tell the story.

There are mythical elements in the film, and an incestuous undercurrent with the characters. The audience doesn’t have to know that, but if they get it, that’d be great.

Now that you’ve made Ylion and Callysia, do you intend to focus on 3D animation from now on, or will you go back and forth between 2D and 3D animation?

I haven’t decided where to go yet, but I’m happy with both. The main difference between 3D and 2D animation is that I had to tell the 3D operator on Ylion and Callysia that everything had to look hand-drawn. But this was my first attempt; I didn’t know how much I had to explain! Also, at the pre-production stage, I was told that to have fewer characters, as 3D makes characters more complicated… But that’s pretty much it.

Andrew Osmond is the author of 100 Animated Feature Films.

Akira, anime, Catnapped, Japan, Mysterious Cities of Gold, Nausicaa, Takashi Nakamura, Ylion and Callysia

Leave a Reply