Mobile Suit Gundam

November 16, 2015 · 0 comments

By Andrew Osmond.

It is the year 0079 of the Universal Century. Fifty years have passed since Earth began moving its population into gigantic orbiting space colonies… Nine months ago, the cluster of colonies furthest from the Earth proclaimed itself the Principality of Zeon and launched a war of independence against the Earth Federation. Initial fighting lasted over one month and saw both sides lose half their respective populations. People were horrified by the indescribable atrocities committed in the name of independence. They were at a stalemate…

It is the year 0079 of the Universal Century. Fifty years have passed since Earth began moving its population into gigantic orbiting space colonies… Nine months ago, the cluster of colonies furthest from the Earth proclaimed itself the Principality of Zeon and launched a war of independence against the Earth Federation. Initial fighting lasted over one month and saw both sides lose half their respective populations. People were horrified by the indescribable atrocities committed in the name of independence. They were at a stalemate…

Gundam is (1) a giant humanoid vehicle/suit of armour, piloted by warriors of the future (2) a phenomenally popular line of robot toys in Japan (3) a 1979 animated TV series created to promote the robot toys (4) an ambitious SF epic about humanity, war and evolution, and (5) a decades-old anime super-franchise encompassing more than a dozen TV series, plus movie and video spinoffs, spoofs, video games, comics, novels, theme park attractions, and hundreds of toys.

There’s a lot of Gundam.

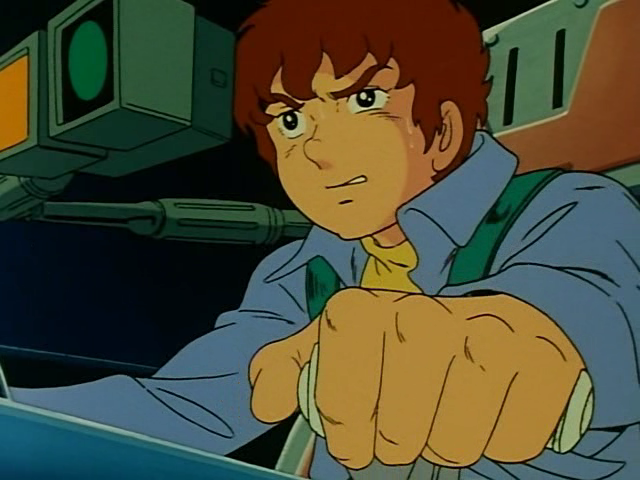

But let’s focus on the original Gundam – the 1979 TV series, which you might like to think of as Star Wars for grownups. Broadcast two years after A New Hope, it’s similarly set in a time of interstellar war, flinging you head-on into the middle of the conflict. Instead of Luke Skywalker, the young hero is Amuro Ray, an electronics geek living on a space colony (‘Side 7’), affiliated with the Earth Federation. It seems like a peaceful backwater from the Earth-Zeon war, until it’s attacked by Zeon soldiers who think it may hide a superweapon.

The Zeons are right. Side 7 is the secret construction site for Gundam, a new kind of ‘mobile power suit’ which could be crucial in the war. The Zeons have power suits of their own, but Gundam is a conceptual breakthrough, containing an A.I. that learns through combat experience. Incredibly resilient, it’s kitted out with weapons including the memorable beam sabre. When a desperate Amuro boards Gundam during the Zeon attack, the machine powers into a super-fighter, making metal mincemeat of the Zeons’ suits. Amuro presumes it’s down to Gundam’s technology, rather than the untrained human pilot… but could there be something special about Amuro as well?

The Zeons are right. Side 7 is the secret construction site for Gundam, a new kind of ‘mobile power suit’ which could be crucial in the war. The Zeons have power suits of their own, but Gundam is a conceptual breakthrough, containing an A.I. that learns through combat experience. Incredibly resilient, it’s kitted out with weapons including the memorable beam sabre. When a desperate Amuro boards Gundam during the Zeon attack, the machine powers into a super-fighter, making metal mincemeat of the Zeons’ suits. Amuro presumes it’s down to Gundam’s technology, rather than the untrained human pilot… but could there be something special about Amuro as well?

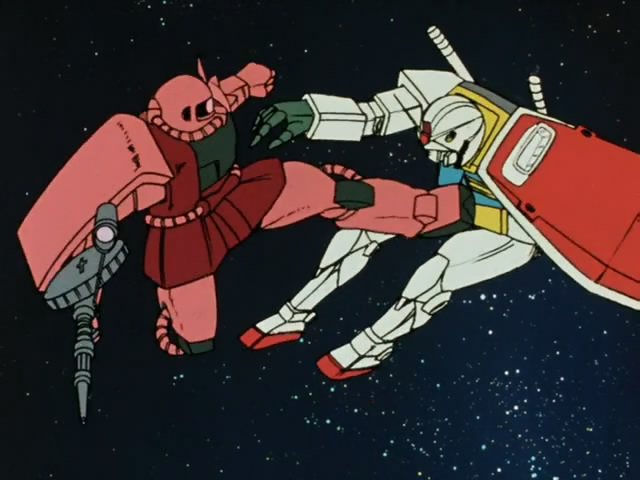

Like Star Wars, Gundam immerses the viewer in a space opera. After the opening fight on the colony, the early episodes are a space chase, with Amuro and other youngsters trying to protect the survivors of Side 7. We get a military spaceship, the White Base, crewed by scared teenagers. Amuro is obliged to defend them singlehanded, fighting bruising duels with the Zeons, giants brawling in the stars. It’s a breathless, unworldly action spectacle, without the comfort of ground or gravity. The story does eventually reach a war-torn Earth, but only after setting out an extra-terrestrial vision as vivid as the opening shot of the giant Star Destroyer in A New Hope.

The difference between Star Wars and Gundam lies in the nature of their wars. In Star Wars, only the villains would use something as terrible as a Death Star. In Gundam, the opening narration makes clear both sides would do that, and have. This is no just war against evil; it’s a story of people who couldn’t choose their sides, who must find their own meanings in what they protect (like Amuro and the civilians of White Base). For creator-director Yoshiyuki Tomino, this view of war is one of the things that makes Gundam into Gundam. In a 2009 press conference, reported by Anime News Network, Tomino reflected, “One thing I think is very unique to the Gundam series is that you have heroes and you have enemies, but they are both viewed as people with concerns. They are both viewed equally… The original story was about human beings.”

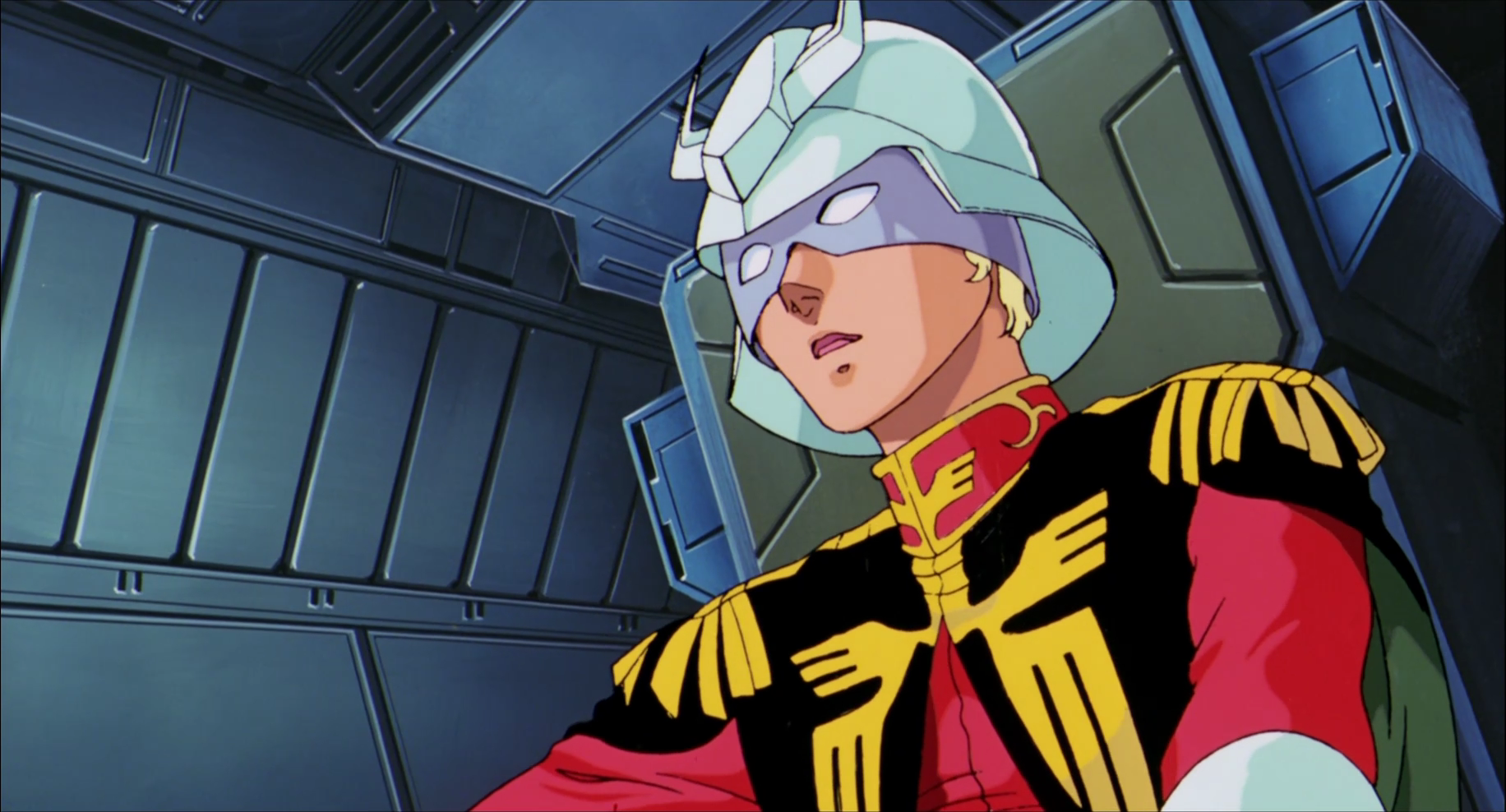

The enemy, Char Aznable, famously steals the show. Whereas the hero Amuro is a callow rookie, Char is presented as a full-fledged warrior and superstar. He has blond hair, a silver helmet, a half-mask and a scarlet power-suit, nodding to one of the character’s inspirations, the Red Baron of World War I. Arrogant and dashing, he has backstabbing plans for his superiors, for reasons revealed slowly (so he’s cool, bad and mysterious). A clue to Char’s origins is presented in the opening battle, where he’s astounded to see a young woman on the Side 7 colony who looks very like his long-lost sister… The backstory of these siblings is filled out in the new anime series, Gundam – The Origin, which began in 2015. If you’ve seen it, you can enjoy the first Gundam as a ‘sequel’ made decades earlier.

The enemy, Char Aznable, famously steals the show. Whereas the hero Amuro is a callow rookie, Char is presented as a full-fledged warrior and superstar. He has blond hair, a silver helmet, a half-mask and a scarlet power-suit, nodding to one of the character’s inspirations, the Red Baron of World War I. Arrogant and dashing, he has backstabbing plans for his superiors, for reasons revealed slowly (so he’s cool, bad and mysterious). A clue to Char’s origins is presented in the opening battle, where he’s astounded to see a young woman on the Side 7 colony who looks very like his long-lost sister… The backstory of these siblings is filled out in the new anime series, Gundam – The Origin, which began in 2015. If you’ve seen it, you can enjoy the first Gundam as a ‘sequel’ made decades earlier.

Gundam’s non-fiction origin lies in the evolution of anime and robots through the 1960s and 1970s. The first big anime robot was Tetsujin-28 in 1963 (called Gigantor in America); this colossus was remote-controlled by its owner. Nine years later, Go Nagai’s Mazinger Z had humans piloting a mechanical figure, beginning a line of “Super Robot” anime for children, tied to successive lines of toys. These series included 1977’s Grendizer, a hit in France as Goldorak. Another was Brave Reideen, co-directed by Tomino, who’d been in anime since he wrote and storyboarded on Astro Boy under Osamu Tezuka.

Tomino got attention for his 1977 robot series Zambot 3, which started as a goofy, cheery kids’ show, but got shockingly nasty in later episodes, with the funny-looking alien villain turning children into bombs. In Anime: A History, Jonathan Clements argues, “Tomino allowed his work to age with the generation that watched Brave Raideen, injecting elements more likely to appeal to more mature audiences.” Zambot helped Tomino earn his nickname of “Kill ’em all Tomino,” because of his readiness to slaughter heroes. We might compare him to Gen Urobuchi, writer of Psycho Pass and Madoka Magica, whose dark, gory subjects got him dubbed the “Urobutcher.”

But Tomino wanted to do more than shock with Gundam. As Masao Ueda, a producer who worked on the series, told Ian Condry in his book The Soul of Anime: “We struggled to make a show that rid itself of the kind of lies that characterised hero programmes up to that point. In Gundam, the robots do not have superpowers. They are just weapons of battle. In addition, most heroes that came before were unrealistically courageous, but in Gundam they had doubts and they were scared. This seemed to us to have much more reality.” Instead of Super Robots, Gundam spearheaded Real Robots – though Tomino disliked the word robot, favouring “Power Suit.”

The ground-breaking Gundam was… a flop. As Ueda explained, Gundam’s toy sponsor Clover didn’t give a fig for the ambitions of Tomino and his team. “Clover complained in many ways. Gundam was too complex, too confusing. It was too dark. Children couldn’t follow what was going on. Clover wanted all kinds of changes. But with animation, you have to plan episodes six months in advance to get them on air. It’s not the kind of thing you can easily change in reaction to audiences… (Clover) just wanted toys to sell.” Disgruntled, Clover ended the show early, cutting Gundam’s twelve-month run to ten.

The ground-breaking Gundam was… a flop. As Ueda explained, Gundam’s toy sponsor Clover didn’t give a fig for the ambitions of Tomino and his team. “Clover complained in many ways. Gundam was too complex, too confusing. It was too dark. Children couldn’t follow what was going on. Clover wanted all kinds of changes. But with animation, you have to plan episodes six months in advance to get them on air. It’s not the kind of thing you can easily change in reaction to audiences… (Clover) just wanted toys to sell.” Disgruntled, Clover ended the show early, cutting Gundam’s twelve-month run to ten.

It seemed an ignominious end, but then a funny thing happened. Clover was approached by another toy company, an outfit called Bandai, which offered to buy the rights to make plastic Gundams aimed at older audiences. The snowball started. Bandai’s models started selling; nourished by the merchandise; a TV repeat of Gundam picked up more viewers. Then the show went to the big screen, compiled into three films blending highlights from the story with new animation. Two years later, Gundam had sold nearly four and half million toys, and a media franchise had begun.

The rise of Gundam coincided with the rise of anime fandom, and also reflected it. Anime fandom predated Gundam – the 1977 film Space Battleship Yamato had given it an early boost – but Tomino’s show was the object of fascination for a certain type of viewer. Satoshi Kon, future director of Perfect Blue, fondly remembered Gundam’s impact at his high school. “My seniors got into Gundam, and that got me into it too,” he said. “We used to watch it enthusiastically, saying ‘That’s so cool!’ or ‘This is absorbing.’ We had lots of what’s called Otakuesque conversations; the errors in my youth, although they’re not really errors.”

There were many details in Gundam to intrigue fans, from the space colonies to the infamous “Minovsky Particles” which inspired intricate fan theories. In fact, Gundam’s script makes wryly clear that these radar-jamming particles were a device to explain why armoured soldiers should fight in close quarters in space, rather than lob missiles from thousands of miles away. Tomino claimed Gundam’s whole creation came from rationalising big robots in such ways. For example, giant robot suits would be ludicrously impractical on Earth, so Tomino took gravity away and set most of the fighting in space.

But there’s one notion in Gundam that’s especially steeped in fan and SF tradition. It’s eventually revealed (small spoiler) that Amuro Ray is a “Newtype,” a new kind of human with sixth senses boosting his fighting skills. You could say that this was a variant on the Force in Star Wars, but the way that the Newtypes emerge in Gundam had a special resonance in Japan. It chimed with changes in the post-war country, with how younger generations seemed to look and think differently from their elders. For example, there was the milk factor. As dairy products became widespread in postwar Japan, so new generations grew up drastically taller than their parents.

As well as milk, there was the Slan factor. Slan was a 1946 American novel by A.E. van Vogt, which posited a new evolution of humanity with psychic powers and other advantages. Slan was embraced by science-fiction fandom as a metaphor for their own potential, their higher intelligence and vision (and their persecution by the less evolved). In the 1940s, “Fans are Slans” was a US geek slogan. Four decades on, the Japanese magazine Newtype, named in Gundam’s honour, became an otaku bible in Japan.

As well as milk, there was the Slan factor. Slan was a 1946 American novel by A.E. van Vogt, which posited a new evolution of humanity with psychic powers and other advantages. Slan was embraced by science-fiction fandom as a metaphor for their own potential, their higher intelligence and vision (and their persecution by the less evolved). In the 1940s, “Fans are Slans” was a US geek slogan. Four decades on, the Japanese magazine Newtype, named in Gundam’s honour, became an otaku bible in Japan.

Tomino himself spoke of Newtypes as imbuing Gundam with significance, above and beyond its achievement as SF. “The kinds of Newtypes we need in the world today are going to surpass even Amuro’s abilities,” he declared. “When we consider our dwindling energy resources, how are people going to survive for the next 10,000 years? I think Amuro is a kind of [shorthand] for the potential that human beings can reach in the future.” Tomino took umbrage at anyone comparing his creation with later SF anime such as Macross and Evangelion. “I believe that the foundation behind Gundam is completely different from these other works… So I would like to really shout at you, don’t you dare compare them.”

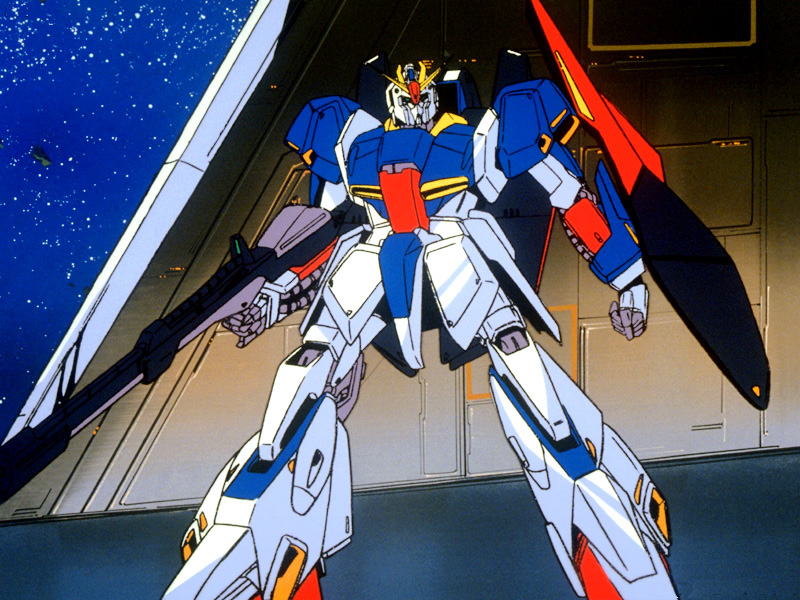

The author built on his foundation in two sequel series, Zeta Gundam (1985) and Gundam ZZ (1986), which were followed by the film Char’s Counterattack (1988). Subsequently, the franchise passed through other hands, starting with Fumihiko Takayama’s acclaimed War in the Pocket (1989), a video series which showed another side of the original war. Not long after, Gundam shows started departing from the continuity of the first series. Instead, they took place in their own universes which could echo the first Gundam – for example, feature enemies resembling the iconic Char – without being restricted by it. A couple of Gundam series even suggest that all the Gundam anime take place in a single millennia-long timeline, one where history re-echoes through the ages.

For decades, the franchise has alternated between other-universe TV series, such as Gundam Wing (1995) and Gundam Seed (2002), and stories returning to the original Gundam timeline, called the Universal Century or UC. The TV shows provide easy starting points for new viewers; the UC titles tend to be serialised on other formats than television, from videotapes to online platforms. The UC Gundams include more side-stories, such as Stardust Memory (1991) and The 08th MS Team (1996). There are also next-gen stories set later in the UC history, such as Gundam F91 (1991), a cinema film by the returning Tomino, his Victory Gundam (1993), the last TV show in the Universal Century, and the lavish video series Gundam Unicorn, released from 2010 to 2014.

As of writing, Gundam – The Origin continues the tradition, delving into the early years of Char, his family, friends and foes. In returning to its roots, the franchise reminds us that, for all the umpteen Gundams there have been, the 1979 series and characters have a unique place in pop-culture. Or as Tomino, not a man for false modesty, put it: “It is not simply a robot story. It is not simply an anime. It is much deeper and much more valuable than that… It is pretty awesome.”

Andrew Osmond is the author of 100 Animated Feature Films. Anime Limited have released Mobile Suit Gundam on Blu-ray.

Leave a Reply