Momotaro, Sacred Sailors

March 9, 2018 · 0 comments

By Jasper Sharp.

Momotaro, Sacred Sailors, a bizarre piece of wartime propaganda targeted at children, coming to UK Blu-ray over 70 years since its original theatrical release in April 1945.

Momotaro, Sacred Sailors, a bizarre piece of wartime propaganda targeted at children, coming to UK Blu-ray over 70 years since its original theatrical release in April 1945.

Sacred Sailors is a monumental work in the evolution of Japanese animation, and a testament to the dark days of modern history, funded by the Japanese Imperial Navy to promote a martial spirit among the young. At 74 minutes, it was the first true feature-length Japanese cartoon, at the maximum allowed running time under wartime austerity measures – the Japanese government began rationing film stock in 1943, bringing an end to the days of 90-minute features

Translated variously as Momotaro’s Divine Sea Warriors, Divine Troops of the Ocean and God Warriors of the Sea, Sacred Sailors is a fascinating film for many reasons, but certainly one that requires a degree of context to appreciate fully. Fortunately, this is provided in spades in Jonathan Clements’ information-packed book that accompanies Anime Limited’s release, chock-full of vital details about it, its director Mitsuyo Seo and his collaborators such as Kenzo Masaoka and Tadahito Mochinaga.

The narrative of the original Momotaro folktale seems particularly well suited for nurturing the national spirit of war-era Japanese youngsters. The titular hero, sent to Earth as a divine emissary from the heavens, is discovered nestling inside a peach found floating down a river by an old childless couple, who raise him as their own. When he comes of age, he marches off to drive a band of boisterous ogres away from their island base of Onigashima (‘Devil’s Island’), picking up along the way a dog, monkey and pheasant to assist him.

An early silent live-action one-reeler was made of Momotaro’s adventures as early as 1915. Like virtually all of Japan’s cinematic output of the 1910s, it has been lost to the ravages of time, but later cartoon incarnations of the Peach Boy do still survive. In 1929, Sanae Yamamoto gave Japanese viewers a more-or-less straightforward retelling of the story in the 9-minute Momotaro is the Greatest, but it was in Yasuji Murata’s Momotaro of the Sky (1931), in which he hopped into a plane with his merry band of animal colleagues, flying down to Antarctica to defend a penguin colony from the attacks of a giant eagle, that his more expansionist ambitions came to the fore.

After Murata’s Momotaro of the Sea (1932), in which Momotaro captains a submarine to battle with a bloodthirsty shark, it is worth singling out one particular outing for our hero, namely Toybox Story Number 3: Picture Book 1936, produced by Takao Nakano for J.O. studios (which was later amalgamated with other companies to form Toho). This film portrays a southern island idyll disrupted by the arrival of an aerial detachment of mice mounted on bats, who commence bombarding the local toy doll population before Momotaro and a cadre of similar folk heroes step in to save the day. Despite the title’s “1936”, the film actually went into production in 1934, a year before Japan’s planned withdrawal from the League of Nations, which threatened its jurisdiction over various territories in the South Seas. The film’s depiction of the island’s invaders, which bear a strong resemblance to a certain well-known Disney character, has given rise to the film’s alternate titling of Momotaro versus Mickey Mouse, and it is interesting to see an American cultural icon so firmly identified as the aggressor this early on in the “Fifteen Years’ War” that began with Japan’s invasion of Manchuria in 1931.

At the time of its release, Mitsuyo Seo’s Momotaro’s Sea Eagles (1943) was the longest Japanese cartoon ever made. It would appropriate another well-known American cartoon character for its depiction of the inhabitants of Onigashima: that of Popeye’s adversary Bluto, who, unlike real-life Caucasians, could be “persuaded” to appear in propaganda form. It’s not like his owners could sue; there was a war on.

This example really highlights one of the major advantages of animation over live-action in depicting the enemy in Japanese films of this period. The lack of available Caucasian performers meant that characters in films such as Masahiro Makino’s anti-British historical drama The Opium War (1943) were unconvincingly played by Japanese actors in Western uniforms and with stick-on facial hair. Consequently, local propaganda films tended to focus on life on the home front and the internal dramas of Japanese soldiers lost in the fog of war.

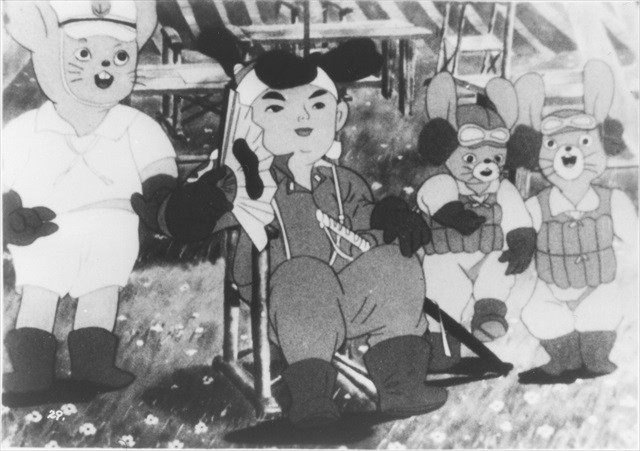

Sacred Sailors plays largely along these lines, with the enemy remaining unseen until the final reel. It opens in the pastoral setting of a forest glade, where skylarks trill and a classroom of infant animals eagerly await the return of their elder siblings on shore leave. We then move on to the far-off tropical base to witness the preparations for the attack. Moon-faced and head wrapped in a “Rising Sun” bandana, Momotaro is the only human presence amongst his animal cohorts. Alongside the parades of monkeys, rabbits and dogs, more exotic creatures such as alligators, tigers, elephants and even kangaroos, racialised through accent and physiognomy, stand in for the native subjects of the lands “liberated” by the arrival of the Japanese forces, their potential harnessed as part of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.

Sacred Sailors plays largely along these lines, with the enemy remaining unseen until the final reel. It opens in the pastoral setting of a forest glade, where skylarks trill and a classroom of infant animals eagerly await the return of their elder siblings on shore leave. We then move on to the far-off tropical base to witness the preparations for the attack. Moon-faced and head wrapped in a “Rising Sun” bandana, Momotaro is the only human presence amongst his animal cohorts. Alongside the parades of monkeys, rabbits and dogs, more exotic creatures such as alligators, tigers, elephants and even kangaroos, racialised through accent and physiognomy, stand in for the native subjects of the lands “liberated” by the arrival of the Japanese forces, their potential harnessed as part of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.

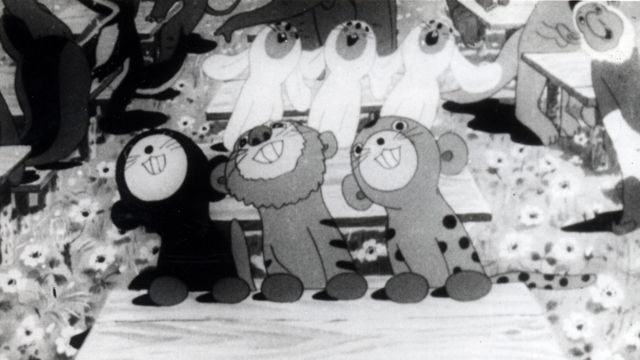

The lion’s share of the movie consists of the animals uniting in rousing marching songs as they toil together under the flag of the Rising Sun: elephants and rhinos uproot palm trees to make space for the military base; monkeys practice hand-to-hand battle with wooden swords; while a pheasant gazes sadly at a photo of the chicks he’s left back home in the family nest. Ships are loaded, parachutes packed and fighter planes are boarded, before the squadron takes off to liberate the beautiful island once ruled over by King Goa. A flashback, poetically rendered in silhouette form, details the arrival of a fleet of black ships bringing a white man who tempts the inhabitants with treasures from far-off lands. Peter High, in his remarkable book The Imperial Screen (2003), describes this interlude as being “in the style of an Indonesian wayang shadow play.”

The air squadron embarks on its mission through dark clouds as a storm descends, recalling similar sequences in Momotaro’s Sea Eagles, and taking a gloomy and foreboding turn from much of the preceding whimsy. Victory is swift and decisive, leading into the film’s most fascinating scene, as Momotaro comes face to face with his enemy. The portrayal of the vanquished Western leader squirming before the Peach Boy’s demands was modelled on actual footage of the British Lieutenant-General Arthur Percival’s encounter with Lieutenant-General Tomoyuki Yamashita after the Fall of Singapore. Known to Japanese audience through their inclusion in the newsreel Malaya War Record (1942), these scenes were later revealed to have been shot under-cranked to speed up the glacial pace of the negotiations. As a result, even the live-action Percival had something of a cartoonish demeanour, appearing as a wildly gesticulating, blinking and fidgety nervous wreck, while Yamashita seemed sharp-thinking, decisive and very much in command (for those interested, the original footage can be seen here).

The air squadron embarks on its mission through dark clouds as a storm descends, recalling similar sequences in Momotaro’s Sea Eagles, and taking a gloomy and foreboding turn from much of the preceding whimsy. Victory is swift and decisive, leading into the film’s most fascinating scene, as Momotaro comes face to face with his enemy. The portrayal of the vanquished Western leader squirming before the Peach Boy’s demands was modelled on actual footage of the British Lieutenant-General Arthur Percival’s encounter with Lieutenant-General Tomoyuki Yamashita after the Fall of Singapore. Known to Japanese audience through their inclusion in the newsreel Malaya War Record (1942), these scenes were later revealed to have been shot under-cranked to speed up the glacial pace of the negotiations. As a result, even the live-action Percival had something of a cartoonish demeanour, appearing as a wildly gesticulating, blinking and fidgety nervous wreck, while Yamashita seemed sharp-thinking, decisive and very much in command (for those interested, the original footage can be seen here).

How influential were the end results? The biggest irony, perhaps, is that when Sacred Sailors opened in Tokyo, the city had been levelled by the devastating American firebombing raids – there was hardly a cinema left standing in which to show it, and the city’s surviving children had been evacuated to the countryside. Within six months, Japan had surrendered and the film, along with so many others produced during the war, disappeared from public discussion and public view. For decades, it was believed that none of the elements had survived Japan’s defeat, until the negative was discovered in Shochiku’s Ofuna warehouse in 1983. This was then duplicated, restored and released the following year, with just one brief sequence missing featuring Bluto and Popeye, snipped from the print due to fears over copyright infringement. The film was re-released theatrically in 1984 on a double-bill with Kenzo Masaoka’s hauntingly beautiful but disconcertingly racist The Spider and the Tulip (1943), and the two films put out on VHS that same year. A DVD followed later in Japan, but Anime Limited’s Blu-ray, taken from Shochiku’s recent 4K restoration, and again with Masaoka’s film bundled into the package, represents the first real opportunity for UK viewers to acquaint themselves closely with this genuine historical curio.

Jasper Sharp is the author of The Historical Dictionary of Japanese Cinema.

Momotaro, Sacred Sailors is released in the UK by Anime Limited.

Japan, Jasper Sharp, Kenzo Masaoka, Mitsuyo Seo, Momotaro, propaganda, Sacred Sailors, The Spider and the Tulip, WW2

Leave a Reply