Seijun Suzuki 1923-2017

February 22, 2017 · 1 comment

The legendary director Seijun Suzuki, who died on 13th February, is best known in the West for such quirky, idiosyncratic works as Youth of the Beast, Kanto Wanderer and Tokyo Drifter. These 1960s B-movie genre pictures playfully riffed on the “borderless action” mash-ups of gangster films, youth movies, musicals and westerns fostered by the Nikkatsu studio, where he was employed from 1954 until 1968, when company president Kyusaku Hori fired him for his “incomprehensibe” hallucinogenic hard-boiled hitman masterpiece Branded to Kill. In Japan, he is remembered for his more critically-regarded ‘Taisho Trilogy’ of Zigeunerweisen, Heat-Haze Theatre and Yumeji – three independently-produced otherworldly tales, released between 1980 and 1991, that marked a short-lived departure towards a more artistic strain of filmmaking.

The legendary director Seijun Suzuki, who died on 13th February, is best known in the West for such quirky, idiosyncratic works as Youth of the Beast, Kanto Wanderer and Tokyo Drifter. These 1960s B-movie genre pictures playfully riffed on the “borderless action” mash-ups of gangster films, youth movies, musicals and westerns fostered by the Nikkatsu studio, where he was employed from 1954 until 1968, when company president Kyusaku Hori fired him for his “incomprehensibe” hallucinogenic hard-boiled hitman masterpiece Branded to Kill. In Japan, he is remembered for his more critically-regarded ‘Taisho Trilogy’ of Zigeunerweisen, Heat-Haze Theatre and Yumeji – three independently-produced otherworldly tales, released between 1980 and 1991, that marked a short-lived departure towards a more artistic strain of filmmaking.

He was born Seitaro Suzuki in Nihonbashi, Tokyo, on 24th May 1923, three months before the city was levelled by the Great Kanto Earthquake. Chaos was a consistency in Suzuki’s life. He was barely out of high school when, in 1943, he was drafted as a private second class and sent by cargo ship to fight on the Southern front, only for his fleet to be destroyed in an American submarine attack. He escaped to the Philippines before boarding a freighter bound for Taiwan, although this, too, was sunk by the US Navy, leaving him floating in the sea awaiting rescue.

He was born Seitaro Suzuki in Nihonbashi, Tokyo, on 24th May 1923, three months before the city was levelled by the Great Kanto Earthquake. Chaos was a consistency in Suzuki’s life. He was barely out of high school when, in 1943, he was drafted as a private second class and sent by cargo ship to fight on the Southern front, only for his fleet to be destroyed in an American submarine attack. He escaped to the Philippines before boarding a freighter bound for Taiwan, although this, too, was sunk by the US Navy, leaving him floating in the sea awaiting rescue.

After the war, Suzuki joined the Shochiku studio in 1946 as an assistant director. In 1954, he moved to Nikkatsu, which had just recommenced production after a 12-year break, along with a number of other Shochiku employees (including Shohei Imamura). Suzuki would make his debut in 1956 with Harbor Toast: Victory is in Our Grasp and went on to direct around several titles a year across the following decade.

His first film directed under the name Seijun Suzuki in 1959, was Underworld Beauty, was part of an early run of stylish mystery-crime thrillers that, like his earlier Voice Without a Shadow and Take Aim at the Police Van, have only recently made it to Western audiences on DVD. Shot in monochrome widescreen and featuring some tense and inventively-staged action sequences within, given his later films, surprisingly conventional narrative frameworks, they count as some of the his most accessible and impressive works. His first colour film, the 1960 comedy youth movie Fighting Delinquents, about a teen yakuza’s attempts to claim an unexpected family inheritance, is indicative of the increasingly cartoonish approach that the director would take to the run-of-the-mill scripts of programme pictures such as Detective Bureau 23: Go to Hell, Bastards!, Our Blood Won’t Allow It and The Flower and the Angry Waves.

Realism was never a strong component in much of Nikkatsu’s output at the time, but Suzuki increasingly went beyond his contemporaries in filling his screen with colour and action, in a style marked by unconventional camera set-ups and editing rhythms, and an incongruous use of costumes, locations and weather conditions. “In my films, time and place are nonsense”, he told Tom Mes in an interview from Midnight Eye, going on to explain that many of his more curious directing decisions were necessitated by low-budgets and tight shooting schedules: “It was more of a job than getting any kind of enjoyment out of making a film.”

Nevertheless, there were works that touched on more serious topics, namely Gate of Flesh (1964) and Story of a Prostitute (1965), female-centred dramas looking at post-war prostitution and military comfort women respectively, and Fighting Elegy (1966), in which a cast of brawling high-schoolers were framed against the backdrop of Japan’s rising militarism of the late-1930s. Branded to Kill, too, despite its oblique approach, is a remarkably robust and original take on the hitman genre: Nikkatsu’s restriction of Suzuki to monochrome film stock in order to restrain the more expressionistic excesses of his colour films (such as Tokyo Drifter, pictured) resulted in a visually striking onscreen world that exists within its own abstract logic. Unfortunately, it proved too much for his employers, who sacked him and withdrew his films from circulation. Suzuki sued for unfair dismissal, and found himself blacklisted from the industry until his comeback in 1977 for Shochiku, Story of Sorrow and Sadness, which proved something of a commercial misfire, and the more successful relaunch of his filmmaking career with Zigeunerweisen.

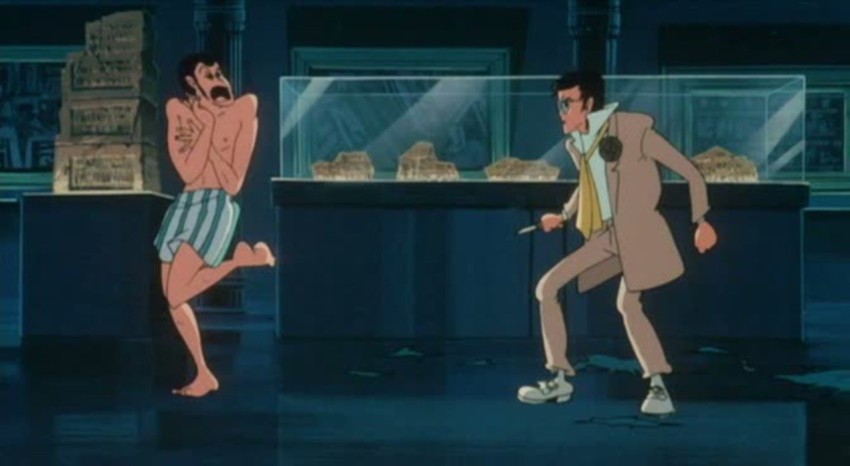

Suzuki’s direct engagement with the world of anime came in 1985 with the Lupin III movie Legend of the Gold of Babylon. Flushed with the success of Hayao Miyazaki’s earlier Castle of Cagliostro, the producers hoped to find a similarly big name, and initially hired Mamoru Oshii on Miyazaki’s recommendation. Oshii, however, provided a script that was characteristically off-the-wall, unhelpfully deconstructing many elements of the Lupin III franchise, and not actually featuring Lupin at all, choosing instead to focus on the detectives trying to track him down. He was thrown off the project before a single frame had been drawn, although certain elements of the Babylon script would be recycled in Oshii’s later works. These included sleuths on the trail of an absent master criminal in Patlabor 2, the ambiguous antagonist of his Ghost in the Shell, and “angel fossils” that would crop in both Angel’s Egg and 009 RE: Cyborg (to which Oshii was originally attached).

Suzuki’s direct engagement with the world of anime came in 1985 with the Lupin III movie Legend of the Gold of Babylon. Flushed with the success of Hayao Miyazaki’s earlier Castle of Cagliostro, the producers hoped to find a similarly big name, and initially hired Mamoru Oshii on Miyazaki’s recommendation. Oshii, however, provided a script that was characteristically off-the-wall, unhelpfully deconstructing many elements of the Lupin III franchise, and not actually featuring Lupin at all, choosing instead to focus on the detectives trying to track him down. He was thrown off the project before a single frame had been drawn, although certain elements of the Babylon script would be recycled in Oshii’s later works. These included sleuths on the trail of an absent master criminal in Patlabor 2, the ambiguous antagonist of his Ghost in the Shell, and “angel fossils” that would crop in both Angel’s Egg and 009 RE: Cyborg (to which Oshii was originally attached).

Having lost their big name from the anime world, the producers of Babylon instead approached Suzuki, freshly returned from a 1984 retrospective of his films at the Pesaro Film Festival. Works like Branded to Kill and Tokyo Drifter were, after all, now regarded as touchstones by the animators of the original Lupin III TV show, making the approach to Suzuki less strange than it may at first have appeared. Suzuki penned an October 1984 episode of the Lupin III TV series, “Variation on a Joke”, in which the master-thief sneaks into a party in a castle that turns out to be a rocket ship, which deposits him in a distant country where he is due to be executed. He escapes amid a storm of crows, in a story that certainly lived up to Suzuki’s surreal standards — considering the timing, the episode may represent a discarded plot idea for the Babylon project.

For those who had only seen the TV incarnation of Lupin III, Suzuki’s movie version was a surprising return to the character as he was originally depicted in Monkey Punch’s manga — in the words of critic Michael Toole, as “a rough, drunken, lecherous crook.” Leaning to some extent on the contemporary popularity of Indiana Jones, Babylon featured a quest for golden tablets beneath New York, thought to reveal the location of buried treasure. The location pits Lupin against not only his usual nemesis Inspector Zenigata, but two feuding mafia families, in a narrative crawling with hallmarks of Suzuki’s signature style. In an ironic turn of fate, the fact that Babylon was a Suzuki film would come to haunt it, as his rising profile abroad led the producers to up the price for its rights. Compared to other films in the anime franchise, it became oddly expensive, a fact which kept it out of some territories for many years.

Pesaro had been Suzuki’s first international retrospective. Few of the films made at Nikkatsu had circulated overseas at the time of their release, and the studio certainly never promoted him as an ‘auteur’ of serious works that could be enjoyed by an international audience. Following ‘Branded to Thrill: The Delirious Cinema of Suzuki Seijun’, a retrospective at the ICA in London in 1994, Tokyo Drifter and Branded to Kill were released by Manga Entertainment on VHS. For an emerging new audience of fans of Japanese cinema, Suzuki became the cult director of choice. Ironically, his filmography is now better represented than any other director who worked at Nikkatsu in his era. There have been many further international retrospectives, notably the one at the ICA which he attended in 2005 to mark the UK release of his final work, Princess Raccoon (2005), a suitably eccentric supernatural musical-comedy starring Jo Odagiri and Zhang Ziyi, and an exhaustive touring programme across North America in 2015, organised by Tom Vick to accompany his book Time and Place are Nonsense: The Films of Seijun Suzuki.

Although he was often dismissive of his early works, Suzuki’s life and the legacy of the 50 titles he’s left behind him, have proven a massive influence on many contemporary Japanese filmmakers. Indeed, it is impossible to imagine a world without him.

009 RE:CYBORG, anime, Branded to Kill, Hayao Miyazaki, Japan, Mamoru Oshii, Manga Entertainment, obits, Seijun Suzuki, Tokyo Drifter

Tamsin Parker

July 8, 2023 1:25 pm

Oshii used his "angel fossil" idea for a Part 6 episode. Was he just listening to the same Kate Bush song again and again?