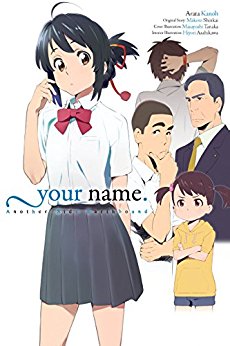

Your Name: Another Side

July 3, 2018 · 0 comments

By Andrew Osmond.

First, this translated spin-off book is not a sequel to Makoto Shinkai’s blockbuster Your Name. Rather it’s an “alternative” retelling of parts of the story, complementing the straight novelisation, which we’ve reviewed elsewhere. Another Side: Earthbound presumes you’ve seen the film, as it leaves out large parts of its plot. The book’s set entirely in Itomori, Mitsuha’s mountain village, and it retells select scenes and situations with different viewpoints from those onscreen.

First, this translated spin-off book is not a sequel to Makoto Shinkai’s blockbuster Your Name. Rather it’s an “alternative” retelling of parts of the story, complementing the straight novelisation, which we’ve reviewed elsewhere. Another Side: Earthbound presumes you’ve seen the film, as it leaves out large parts of its plot. The book’s set entirely in Itomori, Mitsuha’s mountain village, and it retells select scenes and situations with different viewpoints from those onscreen.

Whereas the straight novelisation was written by Shinkai himself, Another Side is by author Arata Kanoh. There’s no indication that Kanoh drew on Shinkai’s notes, nor discussed the film with him. It’s certainly possible, but Another Side may be just Kanoh’s own take. For some fans, that would make it no better than fan fiction. However, it’s an interesting book, especially in the closing section which turns into an excellent prequel, then dares to reinterpret a key point in the film itself. More on that later.

Whereas the straight novelisation was written by Shinkai himself, Another Side is by author Arata Kanoh. There’s no indication that Kanoh drew on Shinkai’s notes, nor discussed the film with him. It’s certainly possible, but Another Side may be just Kanoh’s own take. For some fans, that would make it no better than fan fiction. However, it’s an interesting book, especially in the closing section which turns into an excellent prequel, then dares to reinterpret a key point in the film itself. More on that later.

The book’s four sections each focus on a different character. The first looks at how the boy Taki fares when he must live in the body of a country schoolgirl. In the film, that was mostly reduced to a few humorous glimpses, mainly during the “Zen Zen Zense” music montage. An obvious way to start would have been with Taki’s first swap, when the whole thing’s a freaky Ranma nightmare for him, but instead Kanoh shows his life when he and Mitsuha have been swapping for a while – the book’s first three sections fit into the first half of the film, before that twist.

The Taki section is ominously called “Thoughts on Brassieres”, conjuring visions of an ecchi borefest, but it’s actually pretty decent. Kanoh’s good at rounding out the film scenarios in ways that seem thought-out and believable. Yes, there’s some breast-groping – blame Shinkai for that! – but soon the book’s imagining subtler implications of body-swapping:

“Mitsuha’s reach was just a hair short. When [Taki] tried to pick up a pen or anything like that, something just felt off. When he walked somewhere he knew, it usually took more steps than he expected to get there. This vague dissonance was trouble. Since it was only slight, it hit him when he got careless, which was rough on the nerves.” (Incidentally, the book acknowledges Tenkosei, a live-action Japanese film from 1982 about a body-swapping boy and girl, and its source novel by Hisashi Yamanaka.)

Taki is a central Tokyo boy raised “on the inside of the Yamanote railway loop”, but he finds Itomori life deeply nostalgic, down to the feeling of mountain breezes on “her” skin. This is a common Japanese theme – see anime films like Only Yesterday and The Wolf Children – but Kanoh describes it rather beautifully. It’s also nicely ironic, given that some of Itomori’s locals have very different perspectives on their town, not to mention our knowledge of how the film ends.

There are goofy moments, of course, such as Taki impressing schoolmates with his moonwalking, leading to Mitsusha irritably texting him, “No Michael.” There’s also a wardrobe mishap in a basketball game – a moment that was glimpsed in the film, and helped give it a 12A certificate in Britain. That’s why the next time Taki swaps, he must negotiate the mysteries of the bra…

But Taki also starts wondering about Mitsuha, the girl he inhabits with total intimacy but who he’s never actually met. How can a girl who – he realises – has such a constricted, repressed existence in her own town be so bold when she lives out Taki’s life in Tokyo? This leads on to reflections on a person’s “inner” and “outer” selves, which might be profitably followed up in a live-action Your Name remake, should it actually go into production.

But Taki also starts wondering about Mitsuha, the girl he inhabits with total intimacy but who he’s never actually met. How can a girl who – he realises – has such a constricted, repressed existence in her own town be so bold when she lives out Taki’s life in Tokyo? This leads on to reflections on a person’s “inner” and “outer” selves, which might be profitably followed up in a live-action Your Name remake, should it actually go into production.

The book’s next section takes the viewpoint of Tessie (properly Teshigawara), Mitsuha’s male friend in Itomori, who harbours an ill-concealed crush on her. It’s another good read, even if much of it is a direct retelling of the film’s early scenes from Tessie’s perspective. In other words, it’s the kind of thing that a “straight” novelisation might have done.

Kanoh takes a minor moment from the film, in which Tessie is walking with Mitsuha and their mutual friend Sayaka, both girls happily moaning about how awful the country is, and Tessie has a mild blow-up. In the book, we get to explore Tessie’s own mixed feelings about Itomori. In particular, we see how he, like Mitsuha, is stuck in Itomori by his own circumstances, as the son of a construction magnate– Teshigawara’s family had sunk its roots as deeply as possible into the local soil.

Tessie’s feelings about the town are love-hate. Kanoh throws in a literary reference, to “a novel about somebody who set fire to a temple because they loved it so much that it hurt to the point where they became obsessed with the desire to just make it go away.” (The Temple of the Golden Pavilion by Yukio Mishima.) In his dark teenage moments, Tessie fantasises about blowing the town sky-high. If only he knew…

The third section, from the angle of Mitsuha’s kid sister Yotsuha, is the book’s weakest. It’s played largely for humour, as Yotsuha tries to make sense of her sibling’s sudden “madness”, but the comedy is broad and laboured. There’s an unexpected development (don’t drink that sake!) which allows for a rather beautiful cosmic vision. But maybe Kanoh should have picked a different Itomori character to explore; perhaps Mitsuha’s class teacher, who seems to be a parallel-world version of the woman in Garden of Words.

The book’s last and longest part (a third of the book) is the most compelling. The viewpoint character is Mitsuha’s estranged father, Toshiki, who only had brief moments in the film. In the book, his story starts and ends during the film’s climax. We join him after his angry confrontation with Taki in Mitsuha’s body, when he senses that his daughter is someone else. “A false version of his daughter had come to see him… So that’s what it’s like to encounter a monster.”

The book’s last and longest part (a third of the book) is the most compelling. The viewpoint character is Mitsuha’s estranged father, Toshiki, who only had brief moments in the film. In the book, his story starts and ends during the film’s climax. We join him after his angry confrontation with Taki in Mitsuha’s body, when he senses that his daughter is someone else. “A false version of his daughter had come to see him… So that’s what it’s like to encounter a monster.”

From there, the story moves into flashback, as the encounter awakes memories of Toshiki’s younger life. Before the priest, before the politician, he was a folklorist, who came to Itomori to investigate its distinctive legends and traditions. The shrine matriarch (Mitsuha’s future granny) isn’t welcoming, but her daughter is far friendlier – indeed, she acts like she knows Toshiki already.

The tale that follows is touching and rich, bound up with discussions of real Shinto traditions like that of the deity Shitori (or Shidori) no Kami, a god of weaving who subdued a star god. (Think about the film’s plot a moment – yup.) It’s a very satisfying filling of Your Name’s backstory, coupled with a believable relationship. Toshiki isn’t smitten with his future wife at first sight – or at least doesn’t think he is – but nor is he some floppy caricature of awkwardness.

He’s actually very likable, and much of the story’s pathos comes from our memory of the cold figure he’s destined to become in the film. The book shows Toshiki’s descent skilfully, and his real motives in entering politics. Like Tessie, he has thoughts of “burning the temple.” Then the book returns to the middle of the film’s climax… (Small spoilers follow.)

It’s the end that will annoy some readers – indeed, judging by Amazon reviews, it’s already done so. The reason is that it fills in a scene that Shinkai left artfully blank. This is when Mitsuha, now the real Mitsuha, strides into her dad’s office to confront him for the last time as the comet falls. In the film, we were left to imagine what she said and did. Given how the story came out, we presumed it was something darn dramatic.

In the book… I won’t spoil it, of course. But many fans will think it betrays the film, because Mitsuha’s own agency is no longer the centre. No, the book doesn’t use an obvious plot twist; it’s smarter and more elegant than that, tying the story up rather movingly. Even so, a lot of readers will insist it’s absolutely the wrong end in this case.

Funnily enough, this parallels the arguments about another recent blockbuster, The Last Jedi. There’s been a lot of commentary, positive and negative, about how Jedi references contemporary “progressive” values, especially gender, from the evils of mansplaining to the futility of reckless male heroism. Conversely, Another Side’s ending seems to ignore such values.

The book takes an “invisible” scene – a scene that was only implied in the film, but which viewers may well imagine a particular way – and then reverses expectations. That’s very similar to what Jedi does several times over to its own “source” film, The Force Awakens. The earlier film’s director, J. J. Abrams, reportedly didn’t cook up any of Jedi’s shock story twists – that was Jedi’s own director, Rian Johnson – but he supported them wholeheartedly. Does Shinkai see Another Side that way?

Regardless, many progressive-minded film fans who applauded Last Jedi’s move into a “woke” world may angrily reject Another Side. I prefer to see the book as what its name implies; not canon, but a “maybe” version of the story with its internal integrity. Putting it in terms Tessie might like, it collapses a Schrodringer’s Cat in the story in a way that people may dislike, but the alternatives are still there for our imagining.

Of course, the thing that may really annoy some Your Name fans is that we don’t see any of the characters from the Tokyo side, like the schoolboy who found the feminised Taki “cute.” No doubt there’s a whole shelf of Akihabara dojinshi telling his story…

Another Side: Earthbound is published in English by Yen On.

Leave a Reply