Princess Arete

February 11, 2018 · 4 comments

By Andrew Osmond.

The film Princess Arete is the tale of a little girl growing up in a castle, refusing to resign herself to being married to a hunky Prince Charming. Then a sorcerer, frightened by a prophecy about the girl, effectively buys her from her father and imprisons her in his remote castle… but Arete has friends and her wits, and sets about winning her freedom.

The film Princess Arete is the tale of a little girl growing up in a castle, refusing to resign herself to being married to a hunky Prince Charming. Then a sorcerer, frightened by a prophecy about the girl, effectively buys her from her father and imprisons her in his remote castle… but Arete has friends and her wits, and sets about winning her freedom.

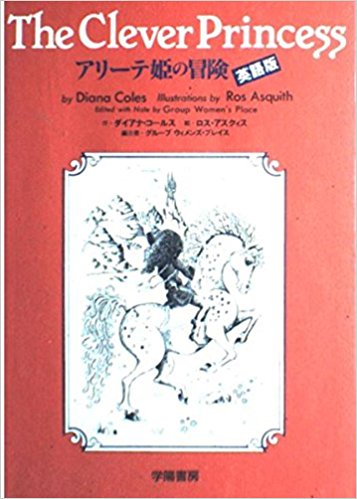

Most anime fans, looking over Arete’s credits, will clock two names. One is the director, Sunao Katabuchi, who has made anime ranging from the lurid Black Lagoon to the lyrical Mai Mai Miracle. He’s now enjoying acclaim for In This Corner of the World, an anime film about a Japanese woman’s life in World War II. You may also recognise Arete’s animation team, Studio 4°C, which made Tekkonkinkreet, the Berserk film trilogy and much of Animatrix. But anime fans may not recognise the source story, a British children’s book called The Clever Princess.

Today, the phrase “cultural appropriation” has become a sledgehammer to denounce moral crimes, and damn the messiness, the to-ing and fro-ing exchanges between cultures through history. Few anime fans, though, have a problem with anime’s appropriations of British children’s literature. The most famous of these are Ghibli’s adaptations: Howl’s Moving Castle, When Marnie Was There and The Borrowers. Studio 4°C’s version of The Clever Princess is in the same mould.

The original book was published in 1983 by Sheba Feminist Publishers, which described itself as “an independent publishing co-operative which produces books by and about women.” Several of its titles were for younger readers, including Girls Are Powerful, a collection of writings from the feminist magazines Spare Rib and Shocking Pink.

The original book was published in 1983 by Sheba Feminist Publishers, which described itself as “an independent publishing co-operative which produces books by and about women.” Several of its titles were for younger readers, including Girls Are Powerful, a collection of writings from the feminist magazines Spare Rib and Shocking Pink.

“When I wrote the story I was living in Greece,” explains author Diana Coles, “teaching English as a foreign language for a few hours in the evenings and lying in the sun drinking retsina during the day. I fell in with a group of young English-speaking expats including a number of radical feminists, who fed me appropriate literature. Woman on the Edge of Time was one book I remember, and Small Changes [both by Marge Piercy]. I didn’t read Angela Carter [who wrote adult feminist treatments of fairy tales in her 1979 book, The Bloody Chamber] until many years later. At the time it seemed very original to be turning the fairy tales norms on their heads.”

The Clever Princess was just one of Coles’ writings. “I wrote a lot of stuff – a sci-fi novel, a silly story about a cleaning lady who changed the world and other stuff. When I came back to England it all got left in a suitcase until I met an old friend. When I had last met her, she had just had a book published and I was about to go to Greece and we said how we each wanted to do what the other had done. This time she told me she was about to go abroad so I had better get my book written. I pulled it out of the suitcase and sent it to Sheba. They accepted it and published a small run in, I think, 1983.”

The sixty-page book comprised eight chapters which could each be a bedtime read-aloud for parents. It’s a feminist fairy tale, of course, where Princess Arete is a fully active protagonist, unlike the archetypal Snow White or Cinderella. The English edition was illustrated by Ros Asquith, now a prolific author and cartoonist. Asquith’s pictures in Clever Princess have humour and charm, as well as extra text for kids to read. But they also have a sense of mystery and wonder, and are never too cute; they’re far from Quentin Blake.

The sixty-page book comprised eight chapters which could each be a bedtime read-aloud for parents. It’s a feminist fairy tale, of course, where Princess Arete is a fully active protagonist, unlike the archetypal Snow White or Cinderella. The English edition was illustrated by Ros Asquith, now a prolific author and cartoonist. Asquith’s pictures in Clever Princess have humour and charm, as well as extra text for kids to read. But they also have a sense of mystery and wonder, and are never too cute; they’re far from Quentin Blake.

“I love that book,” Asquith recalls. “It was the first I illustrated and I was influenced then by Pauline Baines, who illustrated the Narnia books. I wanted Arete to be mysterious, which is why she wears gloves and is only seen from the back. She could be any colour, I hope. As to the humour and mystery (of the pictures), I think I was reflecting the nature of the text, in which the wonder of traditional fairy tale dominates despite being subverted by radical humour. It was, I think, a trail-blazing feminist story.”

Clever Princess came to Japan in 1989, translated by four women who’d come together as Group Women’s Place. In their foreword to the Japanese edition, which renamed the story The Adventure of Princess Arete, they wrote, “We were very glad to find at last a story of a girl who can tackle and overcome difficulties on her own… It would be wonderful if Princess Arete, who is really courageous, clever, generous and vigorous, becomes a popular model for young girls.”

The best source on Arete’s reception in Japan is an essay by Hideko Taniguchi, published (in English) in Studies in Languages and Cultures and available online. Taniguchi explains that, at first, no Japanese publisher was interested in A Clever Princess, but eventually its feminist subject attracted a Yokohama women’s centre, which supported the Japanese edition. The Japanese edition was published with a shocking pink cover, “the colour associated with woman and girl power.”

The best source on Arete’s reception in Japan is an essay by Hideko Taniguchi, published (in English) in Studies in Languages and Cultures and available online. Taniguchi explains that, at first, no Japanese publisher was interested in A Clever Princess, but eventually its feminist subject attracted a Yokohama women’s centre, which supported the Japanese edition. The Japanese edition was published with a shocking pink cover, “the colour associated with woman and girl power.”

“The Japanese translation of The Clever Princess sold extremely well, and went through eight editions in just the first three months,” Taniguchi writes. Two more versions were published: The Clever Princess: English Language Textbook with Japanese Annotations and The Adventure of Princess Arete: A Picture Book. Taniguchi continues:

“Women’s centres and public and school libraries put (Arete) on a recommended reading list. Many young girls welcomed and admired the self-reliant, clever and wise Arete. Many pupils and students wrote essays on it, and a female junior high school student wrote an essay titled ‘I Want to Be a Princess Arete’ and got the first prize in a nationwide essay contest… Asahi Shinbun, one of the leading newspapers, approved of the heroine as a new role model for today’s young Japanese girls in its column. Several theatrical companies, inspired by the story, wrote and performed plays or musicals with such titles as Arete and The Adventure of Princess Arete.”

Coles was not involved in the Japanese publication. “The negotiations were handled by Sheba,” she remembers. “Some years later, about the time Sheba was folding, it was approached by the theatre company Himawari, who wanted to use the book for a play. The person who did the negotiating was Simon Sherwin. I met with him and we got on very well. He arranged for me to meet the owner of the Himawari company, and we had lunch in London. As far as I can remember, we mainly talked about Toshiro Mifune whom his father had worked with and whose acting I greatly admired.”

The play also gave Coles the opportunity to go to Japan. “When the play opened in Tokyo, I was invited over and stayed in a very nice hotel in Tokyo with my son. I was treated extremely well and went to the opening of the play and out to dinner with different people. There were noises being made by the film company at that time and we did have a meeting with them. I also met with women from a women’s collective who had produced a version of the book.”

The play also gave Coles the opportunity to go to Japan. “When the play opened in Tokyo, I was invited over and stayed in a very nice hotel in Tokyo with my son. I was treated extremely well and went to the opening of the play and out to dinner with different people. There were noises being made by the film company at that time and we did have a meeting with them. I also met with women from a women’s collective who had produced a version of the book.”

Coles spoke to the women she met about her surprise that her book had become so popular in Japan. “They indicated that it was partly because it was decrying the idea of arranged marriages, which many Japanese women were trying to break free from. I gave a talk to the women’s collective from Hiroshima. As I remember we talked quite a bit about politics. Afterwards one woman asked me for the text of the talk I had given and sent me a book in exchange called ‘How to bring up a boy’, discussing how to raise male children as feminists.”

On other reactions from Japan, Coles says, “I saw letters that had been written about the play rather than the book but they didn’t come to me but to the theatre company. They generally talked about how Arete is a strong girl and doesn’t need to be rescued.”

The animated film of Arete appeared in Japan in 2001, more than a decade after the book’s Japanese debut. “The film company took an option on rights to use the story but did nothing with them for ages,” says Coles. “Eventually they informed me by post that they were going to make the film and sent me the money that had been agreed. They didn’t send me a copy of the film which I was sorry about. I have had no communication with them since their payment for taking up the option. I think the company has changed names since I signed the original contract with them.”

The animated film of Arete appeared in Japan in 2001, more than a decade after the book’s Japanese debut. “The film company took an option on rights to use the story but did nothing with them for ages,” says Coles. “Eventually they informed me by post that they were going to make the film and sent me the money that had been agreed. They didn’t send me a copy of the film which I was sorry about. I have had no communication with them since their payment for taking up the option. I think the company has changed names since I signed the original contract with them.”

When he stepped up to direct the Arete film, Sunao Katabuchi had already worked on many anime. Black Lagoon was in the future, but he’d served on shows like Arjuna and even Tenjho Tenge (not a fixture on feminist anime lists!) He’d also worked on many children’s shows, including the girl-centred Pollyanna and Tico of the Seven Seas, both part of the World Masterpiece Theatre strand. Katabuchi had also been Assistant Director (under Hayao Miyazaki) on the hugely successful Kiki’s Delivery Service.

In terms of its visuals and leisurely pacing, the Arete film is very reminiscent of the World Masterpiece Theatre shows, a tradition which went back to the 1970s. The style still casts a shadow – the recent series Ronja the Robber’s Daughter may be CGI, but it’s still a throwback to the WMT approach. The Arete film has less comedy than the book, more plaintive melancholy about the sadness of the girl’s position, and also a little more peril. In the opening minutes, for example, Arete creeps up a secret passage to her room and must leap over a bottomless pit, though she laughs gaily when she’s across.

Like many Japanese adaptations of children’s literature, the anime Arete makes extensive changes to the book. Brief episodes are told at much greater length; a kindly witch becomes a cold character; elements of science fiction are added to the story; and will any anime fan be surprised that there’s now a flying machine? Moreover, although the film’s “villain” is called Boax after the book’s baddie, he’s no longer a buffoon but a pitiful figure.

Taniguchi points out the changes to Boax reduce the specifically feminist nature of the book. “The director generalises, or blurs, the feminist theme into the search into the theme of humanity,” Taniguchi writes. “The catch phrase for the animation, ‘A story of a girl who has found the hidden powers of the heart,’ clearly shows its message.” Such a sleight would be controversial today.

Coles has not seen the film yet. “I gather the ending was changed. Not sure how I feel about that. When I wrote (the book), it was before my son was born. Having a boy child does somewhat modify your attitudes – you certainly don’t want to bring your child up to regard himself as in any way ‘the enemy’. This was something I remember discussing with some of the women from the Women’s Collective.”

Coles has not seen the film yet. “I gather the ending was changed. Not sure how I feel about that. When I wrote (the book), it was before my son was born. Having a boy child does somewhat modify your attitudes – you certainly don’t want to bring your child up to regard himself as in any way ‘the enemy’. This was something I remember discussing with some of the women from the Women’s Collective.”

“At the same time I felt it was a bit wishy washy, what (the film makers) apparently did!” Coles continues. “In the original versions of the old fairy stories, wicked step mothers were always getting rolled down hills in barrels full of spikes and wicked step-sisters had their eyes pecked out by talking birds. Being eaten by a snake seems quite mild to me.” (Two men in Coles’ book are turned into frogs and swallowed by a snake – the snake is actually a rather lovable character – though the book’s Boax meets a different end.)

One might argue Coles’ book was distorted as soon as it arrived in Japan. The Clever Princess parodied Western fairy tales; for example, it uses the rule of three, with Arete given three wishes to help her in three tasks (though the joke in the book is that she completes the tasks without needing the wishes). But while Western fairy tales are certainly known in Japan, they seem less culturally fundamental – after all, as they’re only imports. DreamWorks’ Shrek fairy-tale farces were never big hits in Japan, unlike Pixar’s hugely popular Toy Storys.

Japanese creators are blithe about changing foreign stories, even at their deepest level. The Moomins were militarised, for example, while Diana Wynne Jones fans know how much of Ghibli’s Howl’s Moving Castle was unrecognisable from the book, with the film focusing on anti-war sentiments and ad hoc families. To take an adult example, Mahiro Maeda was open about how he “removed the Christianity” from The Count of Monte Cristo when he made his anime of the novel.

But as Taniguchi notes, Katabuchi doesn’t take the princess out of The Clever Princess. Like the book, “the animation movie lays stress on the story of a wise and clever, self-reliant princess, who does the rescuing of herself and others… (and who) would rather live by her own devices and make her own destiny.” For all the story changes, clever children will see the lesson Arete teaches young princesses in a patriarchal world – beware Prince Charming.

Andrew Osmond is the author of 100 Animated Feature Films. Princess Arete is released in the UK by Anime Limited.

dakka yoo

November 10, 2022 8:34 am

ty for this article. Do you think it'd be possible for you to link me to your source(s) for Diana Cole's interview/comments on the book/film. if it'd be possible, I'd rlly rlly appreciate. ty for your time.

Andrew Osmond

November 10, 2022 9:25 am

Thanks for your query: I wrote the article. The comments by both Diana Cole and Ros Asquith came from my personal email communication with both of them, at the time I wrote the article in 2018.

dakka yoo

November 14, 2022 2:50 am

Understood, thank you,, take care.

Alves

November 22, 2022 11:50 pm

Hello, how did you find Coles contacts? I want to write an article on The Clever Princess and it's movie adaptation, considering the "ancientpunk" aesthetic present in the movie and the thematics behind it, but i can't find any way to email the author.