Books: The Early Miyazaki

July 12, 2018 · 0 comments

By Andrew Osmond.

It’s been only months since the publication of Princess Mononoke: Understanding Studio Ghibli’s Monster Princess, an anthology of papers about Miyazaki’s fantasy blockbuster (reviewed here). Today Bloomsbury releases another Miyazaki book, Hayao Miyazaki: Exploring the Early Work of Japan’s Greatest Animator. This one’s by a solo writer, Raz Greenberg, who’s written on anime with both academic and fan hats on.

It’s been only months since the publication of Princess Mononoke: Understanding Studio Ghibli’s Monster Princess, an anthology of papers about Miyazaki’s fantasy blockbuster (reviewed here). Today Bloomsbury releases another Miyazaki book, Hayao Miyazaki: Exploring the Early Work of Japan’s Greatest Animator. This one’s by a solo writer, Raz Greenberg, who’s written on anime with both academic and fan hats on.

Despite being published by Bloomsbury Academic, Greenberg’s book is on the populist side of the fence. It doesn’t start with a sentence like, “Friction, as Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing reminds us in her 2005 ethnography of global connections…” (That’s the first line of Anime Fan Communities, by Sandra Annett.) Early Work is more in the mould of Helen McCarthy’s pioneering Master of Japanese Animation; its approach also reminded me of John Grant’s Masters of Animation. Both books are cited in Greenberg’s bibliography.

The book doesn’t provide much new historical or production information that hard-core Anglophone Miyazaki addicts – the kind who once frequented the venerable Nausicaa.net and have read the 900 combined pages of Starting Point and Turning Point – won’t know or be able to access. In other words, Greenberg’s book is not a font of new info, like the recently-translated Mixing Work with Pleasure or the Japanese-only I am a Gaijin, both written by pivotal Ghibli staff members.

The book doesn’t provide much new historical or production information that hard-core Anglophone Miyazaki addicts – the kind who once frequented the venerable Nausicaa.net and have read the 900 combined pages of Starting Point and Turning Point – won’t know or be able to access. In other words, Greenberg’s book is not a font of new info, like the recently-translated Mixing Work with Pleasure or the Japanese-only I am a Gaijin, both written by pivotal Ghibli staff members.

Rather, the main value of Greenberg’s book is as a friendly way to get lots of information in one place, coupled with the author’s in-depth critique of early Miyazaki which readers can bounce off and argue with (as I’ll do below). It’s accessible to pretty much any reader who knows Miyazaki’s Ghibli films. As least the content is accessible – the actual book, like Bloomsbury’s Mononoke book, has a high price-tag that restricts it to university libraries, though its price may fall.

As the Early Work title suggests, Greenberg is largely concerned with Miyazaki’s pre-Ghibli career, from his first steps as a Toei Studio inbetweener in 1963 to Ghibli’s founding in 1985. The Nausicaa film, if you’ve forgotten, was really a pre-Ghibli work, despite being counted retroactively as a Ghibli production. Actually, Greenberg spends more time on the Nausicaa manga, which Miyazaki at least started before Ghibli.

The book’s first chapter looks at the early Toei animated features which inspired and involved Miyazaki, though he was never their director. The most famous of these films is 1968’s The Little Norse Prince, by Miyazaki’s friend and mentor Isao Takahata. Greenberg also describes the foreign cartoons which helped inspire Miyazaki, such as a 1957 Russian cartoon of The Snow Queen.

We’ll say more on the subject of influences later, but it’s worth noting that Greenberg, talking about anime and manga’s history, repeats an oft-made claim about Osamu Tezuka: that Tezuka’s own drawn style was inspired by the US cartoons of Disney and Fleischer. While this claim is widely believed, it’s also still contested – see this Twitter argument by Rachel Matt Thorn, who translated some of the Nausicaa manga and is now a manga scholar.

The second chapter of Greenberg’s book covers Miyazaki’s TV experience on Heidi and its successors. Again, Takahata was the director on Heidi and two of its much-loved follow-ups, Marco and Anne of Green Gables, though Miyazaki’s titanic contribution to Heidi is legendary. This blog has previously run articles on Heidi’s genesis and legacy.

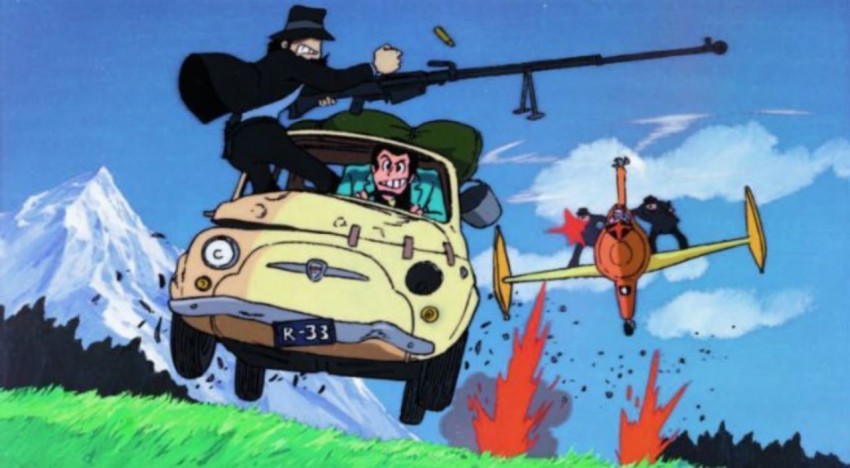

Chapter three looks at Miyazaki’s time on the Lupin III franchise, back when it was a fairly new title, though Lupin has enjoyed a vibrant revival in the 2010s. The same chapter also covers Miyazaki’s episodes of Sherlock Hound, which Greenberg sees as a continuation of the director’s Lupin work.

The fourth chapter covers the manga and film versions of Nausicaa, with a side-trip to explore its precursor Future Boy Conan (1978). This adventure-story serial was the only TV series over which Miyazaki presided as director from start to finish.

The fourth chapter covers the manga and film versions of Nausicaa, with a side-trip to explore its precursor Future Boy Conan (1978). This adventure-story serial was the only TV series over which Miyazaki presided as director from start to finish.

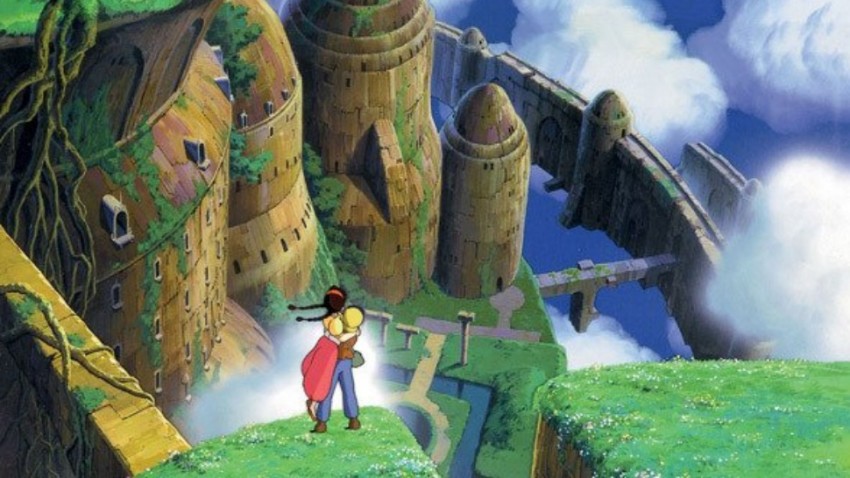

Finally, the last two chapters – the last third of the book – are a whistle-stop tour through all Miyazaki’s subsequent work; from 1986’s Laputa to Wind Rises and Miyazaki’s I’m-not-kidding-this-time-really retirement in 2013. But of course, the discussion of these films focuses on how they’re grounded in Miyazaki’s earlier work and influences; in short, where they came from.

The more intense British and American Miyazaki fans may know about all these anime. However, I think it’s likely that rather fewer have actually seen the anime, let alone analysed them seriously as Greenberg has. Many of the pre-Nausicaa anime with which Miyazaki was involved have never had a commercial English-language release, and viewers may find them hard to sit through.

For example, I personally adore Future Boy Conan, which many fans would agree is thoroughly “Miyazaki” in story and sensibility. Conan’s non-appearance in Anglophone territories was even the subject of a column on Anime News Network. Now, I’ve also tried showing Conan to a number of acquaintances who enjoyed Miyazaki’s Ghibli films. Some of them liked or loved Conan, but several found it almost impossible to watch because of its 1970s kid-friendly style. Even if you can access these old anime, you may still find them “inaccessible.”

For his part, Greenberg grew up with vintage series such as Takahata’s Marco (aka 3,000 Miles in Search of Mother) on Israeli TV. Now he’s diligently gone through the anime most of us haven’t – hands up if you’ve watched all of Heidi, Flying Ghost Ship and Ali Baba’s Revenge. His findings and diagnoses are a large part of the book’s appeal.

And in the spirit of amiable argument, I’d disagree with a great many of them.

Some are particular things, like Greenberg’s curt dismissal of Jimsy, a boy support character in Conan, as a “fat and somewhat selfish boy”, whereas I’d argue he’s one of Miyazaki’s funniest and most loveable creations. Greenberg disses the non-Miyazaki Lupin film Mystery of Mamo (aka Secret of Mamo) as an “overlong messed-up affair”; I think it’s riotously funny. Discussing the film version of Nausicaa, Greenberg asserts that “What does make Nausicaa save the world… is a miracle.” That’s not really how it plays out on screen.

Some are particular things, like Greenberg’s curt dismissal of Jimsy, a boy support character in Conan, as a “fat and somewhat selfish boy”, whereas I’d argue he’s one of Miyazaki’s funniest and most loveable creations. Greenberg disses the non-Miyazaki Lupin film Mystery of Mamo (aka Secret of Mamo) as an “overlong messed-up affair”; I think it’s riotously funny. Discussing the film version of Nausicaa, Greenberg asserts that “What does make Nausicaa save the world… is a miracle.” That’s not really how it plays out on screen.

Just one more of these… Greenberg’s description of Howl’s titular castle as an “ugly, messed-up structure” is surely a typo for “Gilliamesque masterpiece.” Greenberg also claims that Howl’s castle is destroyed at the film’s end, to symbolise the end of childhood. That rather invites the question of what the characters are standing on in the film’s closing shots.

On the subject of childhood’s end, Greenberg confidently asserts that one sign of it is “the discovery of the opposite sex”. Greenberg claims this perspective underpins both early anime which involved Miyazaki, like Anne, and Miyazaki films such as Kiki and Totoro. Yet other Miyazaki films suggest that close, even romantic, boy-girl bonds are hardly incompatible with childhood: see Conan, Laputa, Spirited Away and Ponyo.

Greenberg, while largely praising Miyazaki’s heroines, is less impressed by the male protagonists; saying they tend to be “just too perfect and not that interesting.” That’s a credible viewpoint, but I was more puzzled by Greenberg’s insistence that the boys in these titles are essentially civilised, taming the “jungles” of their anime’s worlds.

Personally, I see characters such as Horus, Conan and Laputa’s Pazu as feral little Ids, driven by instinct and bloody-mindedness. I’d also argue – though I wouldn’t have thought of this without reading Greenberg’s book – that these boys operate both in contrast and in tandem with the girls.

In the anime where the boys are protagonists, the girls tend to be deeper, darker and more troubled – not troubled by trivial or imaginary things, but by real hardships or anguish. A prime case is the tormented Hilda in Little Norse Prince (whom Greenberg dismisses as “an antagonist, or at best a love interest”). It even applies to a film like Mononoke, though we’re far from feral little Ids now.

In the anime where the boys are protagonists, the girls tend to be deeper, darker and more troubled – not troubled by trivial or imaginary things, but by real hardships or anguish. A prime case is the tormented Hilda in Little Norse Prince (whom Greenberg dismisses as “an antagonist, or at best a love interest”). It even applies to a film like Mononoke, though we’re far from feral little Ids now.

Beyond protecting and helping the girls, the job of the simpler-minded boys is often just to cheer them up – rather like Totoro, come to think of it. That even applies to Miyazaki’s Lupin in Cagliostro, who Greenberg sees as another essentially “civilised” man. (Cagliostro spoilers follow.) Greenberg says Lupin turns down the opportunity to “stay with” Clarisse, the film’s heroine, and instead “returns to a life of crime” .This life, Greenberg suggests, is actually protecting the world where the corrupt authorities cannot.

But even if you accept that Miyazaki’s Lupin is only tangentially linked to any other Lupin, the argument seems back-to-front to me. On screen, Clarisse begs Lupin to let her become a thief and join his life of crime. Lupin’s reply is that, having shaken off her family curse, the last thing Clarisse should do is “become all grubby like me.”

Lupin may have exposed global fraud, but purely by accident – his motives were to protect his livelihood and to return a favour. At the film’s end, he’s chasing a set of forged printing plates, as indifferent to the world’s ills as Peter Pan.

A broader issue with the book concerns Greenberg’s emphasis on finding analogies and echoes throughout the anime he discusses, and devoting huge amounts of space to them. That’s not to say there aren’t such echoes; Miyazaki and proto-Miyazaki anime are full of them. But Greenberg takes them to excess, to the point that some of his critiques threaten to turn into laundry lists. I’m also worried that Greenberg often proclaims influences as opposed to parallels.

For example, Greenberg states as fact that Laputa was “strongly influenced” by a 1959 film of Journey to the Centre of the Earth, and that it has “direct visual references” to the original Star Wars. Totoro “makes references to” E.T. The Big Ben finale in Disney’s Great Mouse Detective “paid homage” to Cagliostro. Hakujaden, the 1958 anime feature which Miyazaki loved, was “inspired” by the 1950s British cartoon of Animal Farm.

For example, Greenberg states as fact that Laputa was “strongly influenced” by a 1959 film of Journey to the Centre of the Earth, and that it has “direct visual references” to the original Star Wars. Totoro “makes references to” E.T. The Big Ben finale in Disney’s Great Mouse Detective “paid homage” to Cagliostro. Hakujaden, the 1958 anime feature which Miyazaki loved, was “inspired” by the 1950s British cartoon of Animal Farm.

All these things are possible, but I’m not aware that they’ve been confirmed by the people who worked on the films, and it’s worrying that Greenberg doesn’t provide sources for these claims. I’ve been guilty of such slippage in my own writing, but I’d be grateful for more clarity in a book that devotes so much space to comparing different works.

Taken just as parallels, many of Greenberg’s comparisons are interesting, but some seem stretched to me. On page 94, for example, Greenberg discusses a late section of the Nausicaa manga, where the heroine is waylaid in a garden, loses her memories, and is tempted to abandon her journey. Greenberg argues this homages Star Blazers, aka Yamato. But I think there’s a far more obvious source – a sequence in the Russian Snow Queen cartoon mentioned earlier, which we know Miyazaki loved.

More broadly, one issue with focusing on parallels and homages is that it can be reductive, and treat titles as mere permutations of what’s gone before. Conversely, Greenberg’s book is also very teleological. In other words, it treats the early works as evolving towards later ones… and evolving specifically towards Miyazaki’s famous films, like Totoro and Spirited Away.

So, for example, the monstrous God Warrior at the climax of the Nausicaa film is subject to one of Greenberg’s curt dismissals, as a “mere plot device, a mindless monster.” That hardly seems to do justice to the beast’s visual impact! Many fans see it as the true “arrival” of its animator, Hideaki Anno, and a harbinger of one of the biggest non-Miyazaki anime brands – Anno’s Neon Genesis Evangelion.

Moreover, admirers of Isao Takahata may be indignant that his later work is given short shrift too. That’s the case even though Takahata actually directed many of the titles that the book brings under the heading of “early works” of Miyazaki. Greenberg addresses this subject briefly, saying, “It is hard to discuss (Takahata’s) entire body of work as one of consistent, personal style, like Miyazaki’s.”

But there are obvious parallels between, for example, Takahata’s Kaguya and Heidi forty years earlier. To take another case, the presentation of Marilla, the strict adult guardian charcter in Anne whom Greenberg describes very well in the book, would seem to exemplify Takahata’s “objective” portrayal of characters though his work. And so on.

And to finish off, one part of Greenberg’s discussion prompts an especially dark thought. Greenberg claims that, in an anime like Heidi, “Nature represents childhood, which is celebrated by the freedom of emotion… It is a carefree environment where the individual’s desires and emotions can be freely expressed.”

Now remember that 14 years after Heidi, Takahata would go on to direct a film about two young children who escape their strict adult guardians, who live freely in nature and express themselves… and who then die horribly. So was Grave of the Fireflies actually Takahata’s caution against people reading too much into the ethos of anime he made for children?

Andrew Osmond is the author of the BFI Modern Classic on Spirited Away. Hayao Miyazaki: Exploring the Early Work of Japan’s Greatest Animator is out now from Bloomsbury Academic.

Leave a Reply