Books: Archiving Anime

November 30, 2019 · 0 comments

By Jonathan Clements.

Archiving Movements: Short Essays on Materials of Anime and Visual Media, edited by Minori Ishida and Kim Joon Yang, is related to a patchwork of international initiatives – an anime archiving project at Niigata University, an exhibition in Singapore, and a brief mini-conference in Stockholm. It seems to have been produced as an argument towards how Niigata should proceed with its research, starting with what materials should be preserved, and how they could be studied.

Archiving Movements: Short Essays on Materials of Anime and Visual Media, edited by Minori Ishida and Kim Joon Yang, is related to a patchwork of international initiatives – an anime archiving project at Niigata University, an exhibition in Singapore, and a brief mini-conference in Stockholm. It seems to have been produced as an argument towards how Niigata should proceed with its research, starting with what materials should be preserved, and how they could be studied.

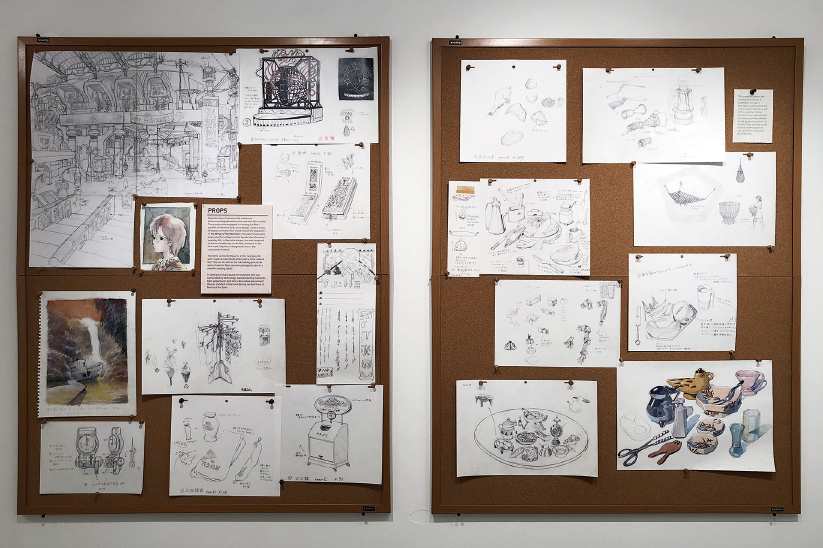

For the sake of argument, the materials presented in the exhibition, and discussed in the conference, were from the Gainax classic Wings of Honneamise (a.k.a. Royal Space Force), made at the tail end of the cel-and-pencil days, but also with the last great gasp of Bubble-era boondoggle money. As chronicled elsewhere, not the least in the memoirs of Toshio Okada, Wings of Honneamise had a gloriously busy, high-quality production history, fought over by its passionate creators, its grim money-man, and distributors and exhibitors determined to turn it into something that it wasn’t. Even the alternate names denote the behind-the-scenes battle over whether interfering producers, determined to call it “The Something of Something”, would get their way, along with an airline sponsor adamant that “Wings” should be in the title.

Director Hiroyuki Yamaga is quoted as mentioning “the essence of a contour” (rinkakusen), a unique signature to be found in the line-art of individual animators, a fingerprint or distinct calligraphy if you will, that encourages the appreciation of anime art at practically a line-by-line level. This, of course, will be catnip for sakuga fans, those connoisseurs of individual frames of anime art, and the way that a bunch of them elide together to form apparent movement. The exhibition, and this publication that derives from it, aims to demonstrate how moments of individual artistic creativity and achievement can contend and blend into a functional whole in the process of creating an animated film.

Gan Sheuo Hui, in her account of the Singaporean exhibition, dives headfirst into material issues, not just over the exhibition of papers, cels and sketches, but over fundamental architectural worries like the effect of the low ceiling and fluorescent lights on the exhibits. Having suffered through the poor layout of the recent Tutankhamun exhibition at the Saatchi Gallery, I am immensely pleased to see someone talking so frankly about issues of the curatorial space, and hope that future exhibition runners can learn a little from her. She has much to say about ways to get visitors to truly interact with the materials on display, such as a cunning little display that allows people to faff with the lighting set-up on a 3D space. “The greatest success of this exhibition,” she writes, “was heightening the attention to the production process, a research area that has long needed careful attention and analysis.”

Gan Sheuo Hui, in her account of the Singaporean exhibition, dives headfirst into material issues, not just over the exhibition of papers, cels and sketches, but over fundamental architectural worries like the effect of the low ceiling and fluorescent lights on the exhibits. Having suffered through the poor layout of the recent Tutankhamun exhibition at the Saatchi Gallery, I am immensely pleased to see someone talking so frankly about issues of the curatorial space, and hope that future exhibition runners can learn a little from her. She has much to say about ways to get visitors to truly interact with the materials on display, such as a cunning little display that allows people to faff with the lighting set-up on a 3D space. “The greatest success of this exhibition,” she writes, “was heightening the attention to the production process, a research area that has long needed careful attention and analysis.”

But there are all sorts of other achievements, not the least her comments in this book about the issues arising in, for example, copyright, when even an animator’s signature stamp on a sketch does not necessarily confer ownership, or even anything more than editorial approval. Auteurist tradition in film would ascribe ownership to the director, as in “Hiroyuki Yamaga’s Wings of Honneamise”, or studio , as in “Gainax’s Wings of Honneamise”, but to whom do the work-for-hire individual artworks “belong”, not necessarily legally (that would be the studio), but creatively?

As Minori Ishida notes in another essay, this is particularly important when discussing image boards, the chaotic, many-artist melting-pots of blue-sky ideas. “Image boards” comments Hiroyuki Yamaga, “are part of the brainstorming phase, when people are drawing without inhibition. That’s why there are a lot of them. They aren’t all usable. Because you won’t get anywhere unless you really go for it, knowing that none of them might be used at all.”

Ishida gets to grips with “intermediate materials” – those 2,500 bits of paper, notes, scribbles and sketches that form the building blocks, or sometimes merely blueprints or even jettisoned concepts for Honneamise, that have been digitally archived in Niigata. She quotes Yamaga on his fears that the Studio Ghibli creative style, which relies on the idiosyncratic hands-on approach of a single director, Hayao Miyazaki, risks being regarded by younger animators as the norm, whereas it is merely one possible approach to the creation of animation.

Ishida gets to grips with “intermediate materials” – those 2,500 bits of paper, notes, scribbles and sketches that form the building blocks, or sometimes merely blueprints or even jettisoned concepts for Honneamise, that have been digitally archived in Niigata. She quotes Yamaga on his fears that the Studio Ghibli creative style, which relies on the idiosyncratic hands-on approach of a single director, Hayao Miyazaki, risks being regarded by younger animators as the norm, whereas it is merely one possible approach to the creation of animation.

Other elements of the book include Dario Lolli on history and technology in Honneamise, Jaqueline Berndt on the history of overseas anime/manga exhibitions (written before the British Museum’s recent triumph), a revealing interview with Hiroyuki Yamaga about the financial underpinnings of Gainax and his own struggles with creating the characters, and Kim Joon Yang asking what archived materials can tell us about anime. He delves deep into some of the directions on storyboards, noting that, say, a Star Wars inspiration is far more arguable in an analysis if we have the director’s own scrawl in the margins, reading “Make this like that scene in Star Wars!”

As a translator in times gone by, I have seen such revelations many times, most memorably on Yoshiaki Kawajiri’s “Slipstream” chapter of The Cockpit, where a controversial line about atomic weapons turned out to be handwritten on the printed script – inserted on the voice-over, not part of the original plan. Kim’s essay makes it crystal clear that there really should be no excuse for the kind of hand-waving speculation about directorial intent that we so often get from cultural studies wonks. In many cases, you can literally buy the storyboards for an anime movie and see precisely what the director was trying to do in a specific shot – to convey the feeling of accelerating on a motorbike, for example, or evoking a particular moment from another film.

A closing essay by Kenichi Harada on other materials in Niigata’s archives emphasises that this 47-page publication, while largely devoted to anime on this occasion, is merely the first volume in an ongoing series that will return, hopefully, to anime soon enough, but also to other issues that deal with the preservation of cultural artefacts in an increasingly digitised world.

Archiving Movements: Short Essays on Materials of Anime and Visual Media is released as a free PDF by Niigata University. Jonathan Clements is the author of Anime: A History.

Leave a Reply